As the activity range of migratory birds is global in scale, it is very difficult to study them, and for a long time, their ecology remained mysterious. Many people are fascinated by migratory birds and find their thoughts turning to the birds’ destinations, which evoke a sense of the seasons and a certain wanderlust. Once tracking studies began to be carried out with the aid of satellites in the 1990s, scientific and technological methods of tracking avian migration were established, and the hitherto-mysterious routes and behavior of migratory birds began to become apparent. At the same time, results have also emerged from field surveys carried out by citizens. Linking these results to science and technology is leading to the discovery of new facts.

Special Feature 1 – Mysteries of Migratory Birds Interesting migration routes identified through public cooperation and satellite tracking

composition by Rie Iizuka

Bird migration conjures up a world of grand dreams and romance for all of us. From the 1950s or thereabouts, scientists conducted a great deal of research and shed light on many aspects in the laboratory, including the physiological functions that make migration possible and the mechanisms behind their sense of direction. Despite this, even the questions of which places migrating birds flew over and where they went remained unanswered. However, in the 1990s, advances in satellite technology made it possible to track avian migration.

A variety of migratory patterns

Migration follows a variety of patterns. One often hears birds described as summer visitors or winter visitors, but their description varies according to the location one uses as the benchmark. For example, in the seasonal imagery of Japanese poetry, swallows (specifically, barn swallows; Hirundo rustica) are associated with spring. This is because, in Japan, these birds arrive in spring and raise their young here, before flying back south sometime between the end of summer and fall. In contrast, in Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines, these swallows are winter visitors that come to spend the winter there. Many species in sandpipers and plovers breed in the Arctic, then travel via Japan and China’s east coast before crossing the Equator and migrating all the way to Australia and New Zealand in the southern hemisphere. As Japan is a stop over for them, they are referred to here as passage migrants.

Then there are small birds like bullfinches (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) and goldcrests (Regulus regulus), which are referred to as wandering birds, breeding in high mountains in spring and summer, then moving further south in fall and overwintering on low plains.

Migratory patterns are generally categorized in this way, but even within Japan, avian behavior often differs completely between Hokkaido, Honshu, and Okinawa Prefecture. As described above, swallows are typically regarded as summer visitors in the Chubu and Kanto regions of Honshu. However, in Kagoshima Prefecture and other southern regions of Japan, they are also seen in winter. Accordingly, in Kyushu, where they are seen throughout the year, swallows are regarded as resident birds (birds that stay in the same place year-round and do not migrate with the seasons). Nevertheless, among the swallows that spend winter in Kyushu are some that migrate down from the continent, so there is a degree of turnover in the population. There are many other such examples. Depending on which region we use as the benchmark, the same bird may be regarded as a summer visitor, winter visitor, passage migrant, resident bird, or wandering bird, which demonstrates that avian ecology is not simple.

So, why do some birds cross tens of thousands of kilometers, while others have an activity range of no more than a few hundred meters or a few kilometers? The answer lies in differences in what they feed on.

As resident birds such as sparrows, crows, and black kites (Milvus migrans) are omnivorous and do not have any special physical features —— for example, a beak that is extremely long or curved upward —— so have virtually no constraints on what they eat. Accordingly, they can sustain themselves even if they stay in the same region.

Migrating in search of abundant food resources

On the other hand, the migratory raptors such as gray-faced buzzards (Butastur indicus) feed on reptiles and amphibians, including snakes, lizards, and frogs, so they adopt habits that make catching such prey convenient, with physical characteristics tailored accordingly. In Japan, gray-faced buzzards can catch a lot of snakes and lizards in spring and summer, but such reptiles vanish in fall and winter. Accordingly, the buzzards migrate to Southeast Asia and remain in the region throughout winter, as snakes and lizards can still be had there during those months.

One might therefore be tempted to think that gray-faced buzzards should simply remain in Southeast Asia, with its ample food supply, throughout the year. However, birds need even more food than usual during breeding season, when they raise their young. The snakes, lizards, frogs, and other creatures on which gray-faced buzzards prey emerge in large quantities in high-latitude areas in spring and summer. The strategy of migratory birds is to travel thousands of kilometers to take these abundant food resources in order to breed.

The most common method used in avian migration research is leg bands. While surveys can easily be carried out in a variety of locations, the low recovery rate is a drawback.

In the 1990s, it became possible to track birds using satellites (hereinafter referred to as “satellite tracking”). Radio waves transmitted by tracking devices fitted to birds are picked up by receivers installed on satellites, and the data is then sent to receiver stations on the ground and information processing centers, enabling time as well as latitude and longitude to be recorded. The margin of error in this location information is no more than a few kilometers and even as little as one kilometer or so. However, as it is difficult to miniaturize the devices fitted to the birds, they can mostly only be used on large birds such as hawks and swans.

Then geolocators appeared on the scene. A geolocator is a tracking device weighing about one gram that records light levels and time. Changes in the recorded light levels enable sunrise and sunset times to be identified; this information is used to calculate the length of daytime and nighttime, from which the subject’s position is estimated. As the devices are tiny, they are making a major contribution to tracking small birds. Although geolocators can sometimes have a margin of error of 100 km or more, they nonetheless represent a major advance, because they have made it possible to track small birds —— something that had, for researchers, previously seemed a pipe dream. As geolocators are also cheap, they are now widely used.

I am involved in various avian satellite tracking surveys. In a project tracking cranes that use Kagoshima Prefecture as a wintering spot, including demoiselle cranes (Anthropoides virgo) that cross the Himalayas, we tracked their migration from Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and Russia. The ability to track birds and see how they behave during their migration was a giant leap forward.

The Korean Peninsula’s demilitarized zone is an important stopover site

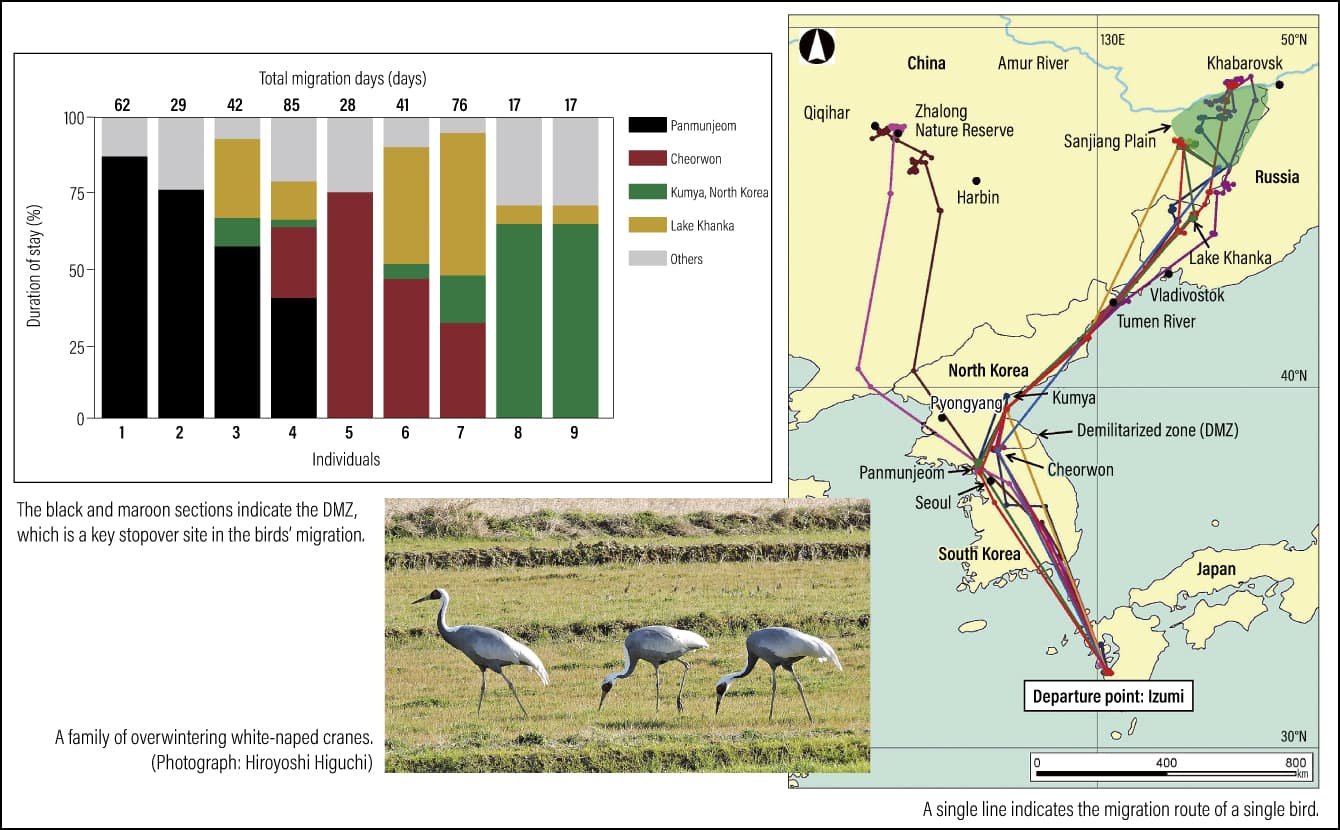

One migration survey that made a particular impression on me focused on the white-naped crane (Grus vipio). We learned that the demilitarized zone (DMZ) on the Korean Peninsula is an important stopover site for white-naped cranes after they leave Izumi City in Kagoshima Prefecture (Figure 1).

Higuchi et al. (1996) Conservation Biology 10: 806-812

Higuchi et al. (1996) Conservation Biology 10: 806-812

Figure 1. The spring migration of white-naped cranes

The figure shows that many birds stay in Panmunjeom and Cheorwon. Some of them even fly back and forth between Panmunjeom and Cheorwon. When we plotted the sites where they stayed on Landsat (Earth observation satellites launched by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)) satellite images, we found that, as expected, they all fitted neatly within the 4 km-wide DMZ and the Civilian Control Zone that stretches for several more kilometers to the south. Somewhat ironically, perhaps, one can see that cranes prefer to stay in an area where no economic activity takes place, as development and entry by humans is restricted. While national borders do not exist for migratory birds, the border is an important place for cranes. In the broadest sense, this was a major finding in early migration research.

With regard to gray-faced buzzard migration, we have obtained highly interesting results from not only satellite tracking, but also observation information.

During their fall migration, gray-faced buzzards headed south from northern Kyushu to the Philippines, but although they would travel via the Nansei Islands, they did not transit Taiwan.

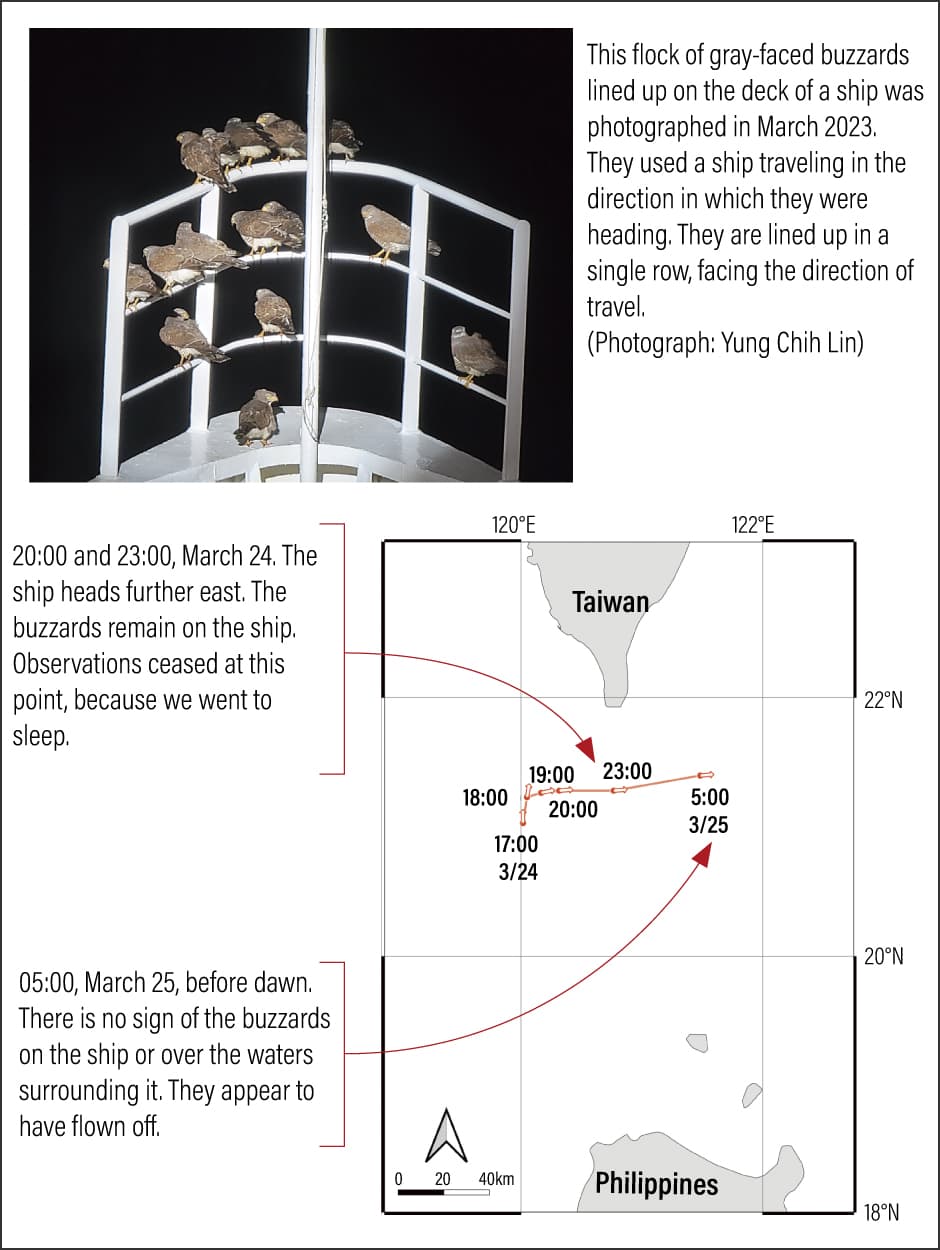

However, they did transit Taiwan during their spring migration. During their journey, the gray-faced buzzards displayed behavior that surprised us. At a latitude of 21°14′ north and a longitude of 120°03′ east, to the south of Taiwan, gray-faced buzzards began to fly about above a ship; then, at a latitude of 21°16′ north and a longitude of 120°10′ east, just as the ship started to change its heading from north to east, the buzzards began to land on the ship (Figure 2).

Wu et al. (2024) Journal of Raptor Research 58: 125-128

Wu et al. (2024) Journal of Raptor Research 58: 125-128

Figure 2. Gray-faced buzzards traveling on a shipThis flock of gray-faced buzzards lined up on the deck of a ship was photographed in March 2023. They used a ship traveling in the direction in which they were heading. They are lined up in a single row, facing the direction of travel. (Photograph: Yung Chih Lin)

While there is scope for further research to determine whether they regularly display this behavior, at the very least, this example demonstrates that the birds were capable of identifying a ship heading in the right direction at the right time and landing on it. I believe this has become one means of migration for them —— finding and alighting on the right ship out of the many ships that pass through the Taiwan Strait each year.

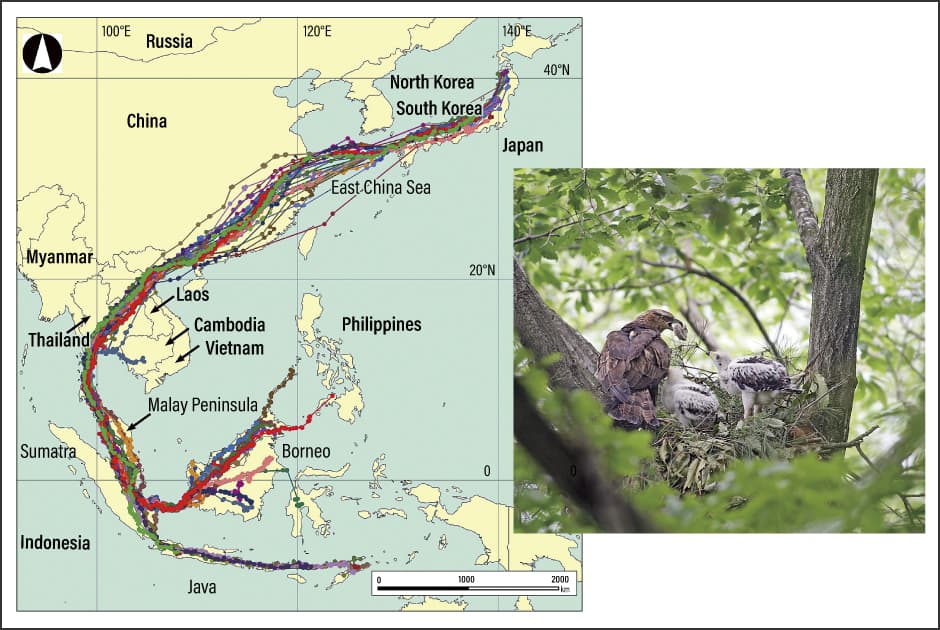

Another bird that, thanks to satellite tracking, gave me cause to think further about the great wonders of migration is the honey buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) (Figure 3). Between 2003 and 2016, we succeeded in satellite tracking of at least 50 honey buzzards. After spending spring and summer at their breeding grounds in Kuroishi City, Aomori Prefecture, and Iide Town, Yamagata Prefecture, they head to wintering spots in Indonesia and the Philippines. However, we discovered that, rather than taking the shortest route, they go quite a long way around to get there. They first head west from Japan, traveling around 700 km across the East China Sea; on reaching China, they fly overland and then head via the Indochinese Peninsula, the Malay Peninsula, and Sumatra, among others, before reaching such destinations as Java, Borneo, and the Philippines.

Higuchi (2012) Journal of Ornithology 153 Supplement:3-14

Higuchi (2012) Journal of Ornithology 153 Supplement:3-14

Figure 3. The distinctive migration routes of honey buzzardsTracking the migration of honey buzzards, the researchers discovered that in fall, the birds take quite a major detour to avoid the sea, flying west from Japan to China, then entering the Indochinese Peninsula before heading to Sumatra and Borneo. It remains a mystery as to why they take a circuitous route that describes a large C shape, even though a direct southerly route would clearly enable them to conserve a substantial amount of both time and energy. Another striking feature is the fact that a large number of the birds take the same route, almost as though there is a road in the sky. The photograph shows a honey buzzard brood. (Photograph: Teruo Nakamura)

The profound wonders of birds’ behavior in real life

During the spring migration, the honey buzzards traveled back via the route they took in fall, but unlike the fall migration, all the birds stayed on the Indochinese Peninsula or in southern China for between a week and a month. After that, they traveled to Kyushu via the Korean Peninsula, rather than crossing the East China Sea. We found that, rather than flying back to their destination in a straight line, they do indeed take a detour on their epic migration of 10,000 km or more each way, but then return to a particular location so precisely determined that it could almost be a street address.

It is known about the mechanism behind avian migration that they use the sun’s position, constellations, geomagnetism, wind direction, topography, and the like to ascertain their direction. However, honey buzzards, for example, are birds that love to change direction at right angles. Even though we understand the simple mechanism for recognizing direction under experimental conditions, there are still mysteries that we cannot unravel, such as why honey buzzards change direction at right angles several times, and how they decide on the direction to take and timing of the turn. The behavior of birds in real life is a source of profound wonder, and it would be fair to say that observing and tracking this behavior is the real pleasure of field research.

We opened the results of satellite tracking of honey buzzards to the public in 2012 and 2013. This project was tremendously inspiring, both because of our results shedding light on their routes and because we were able to share the migration process with so many people. Having named the four honey buzzards that were the subjects of our study, we tracked them in real time, while exchanging information with people in various countries. This process not only brought home to everyone the fact that national borders do not exist for birds, but also helped to forge connections between people through avian migration.

Following these results, in December 2023, we launched the Swan Project (https://www.intelinkgo.com/swaneyes/), a swan migration satellite tracking project accessible to the public (Figure 4).

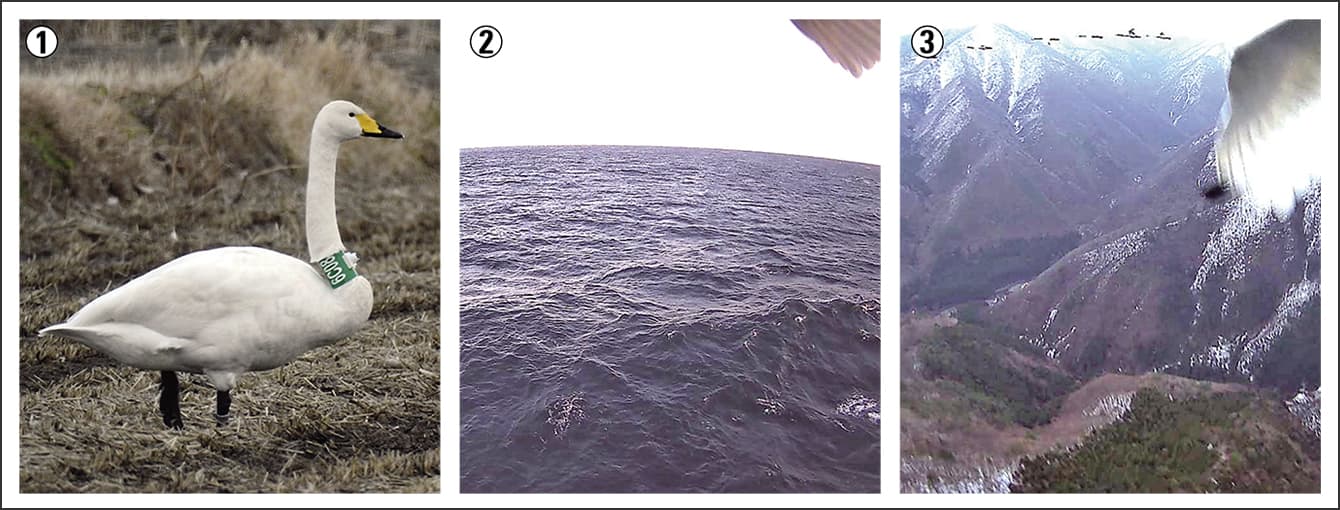

Figure 4. Photographs taken during the course of the Swan Project① 6C08 (nickname: Miho) with a device attached. We give each bird a nickname. ② An image recorded while flying over the Pacific Ocean (March 19, 2024). ③ An image that arrived from the whooper swan Kiyoshi while flying from Akita Prefecture to Aomori Prefecture. In the distance at the top left, you can just make out six companions flying alongside (March 14, 2024).(Photographs courtesy of Tetsuo Shimada, Swan Project)

In this world-first joint international project, which aims to build a framework for the public to watch over swans, we have fitted camera-equipped transmitters to swans on Lake Izunuma in northern Miyagi Prefecture and Lake Kutcharo, near the northernmost tip of Hokkaido. As well as tracking their migration, we make the images captured by the cameras available to the public. We have fitted the devices to a total of 20 whooper swans (Cygnus cygnus) and tundra swans (Cygnus columbianus). Their location information is recorded six times a day at four-hourly intervals, while images are recorded at 07:00, 09:00, 13:00, and 17:00, with this information made available at 01:00, 09:00, and 17:00.

This means that you can see what the swans are doing and where, along with the landscapes that the swans themselves are actually viewing. We show as much of the information we obtain as possible, and members of the public go to the places where the swans are to view them and take photographs of them, which they then feed back to the project. Thanks to this two-way exchange, this project is able to provide a more vivid sense of the nature of swan migration. We are now able to vicariously experience the world of migratory birds, which was formerly the stuff of dreams and legends. And by seeing the birds in flight, many people around the world are giving greater thought to them. Their ideas are joining up and giving rise to exchanges and international cooperation in a variety of forms. It is my hope that this project, too, will lead to cross-border exchanges between people that will generate positive progress in the conservation of birds and their habitats.