Recent years have seen progress in efforts to commercialize cultured meat —— meat cultured from the cells of livestock such as cows, pigs, and chickens. Following hot on the heels of such work are endeavors to develop what could be described as the seafood equivalent: cellular aquaculture. The basic technology is more or less the same as that used for culturing the meat of food-producing animals, relying on cell culture rather than aquaculture. Right now, startups all over the world are competing to develop technology aimed at commercializing what is also being called cell-cultured fish or cell-cultured seafood, and there are reports that tasting sessions are even taking place. Hopes are high for what could be achieved in Japan, which boasts a food culture traditionally centered on seafood and advanced fisheries technology.

Special Feature 1 – The New Era of Protein Resources Cellular aquaculture: High hopes for the seafood equivalent of cultured meat

composition by Toshiko Mogi

illustration by Rokuhisa Chino

The term “cellular aquaculture” is unfamiliar to most people, I think. Rather than catching or farming fish, cellular aquaculture involves culturing cells from fish and other seafood so that they multiply. The product of this process is called cell-cultured fish or cell-cultured seafood.

Culturing cells to produce the tastiest parts of the fish

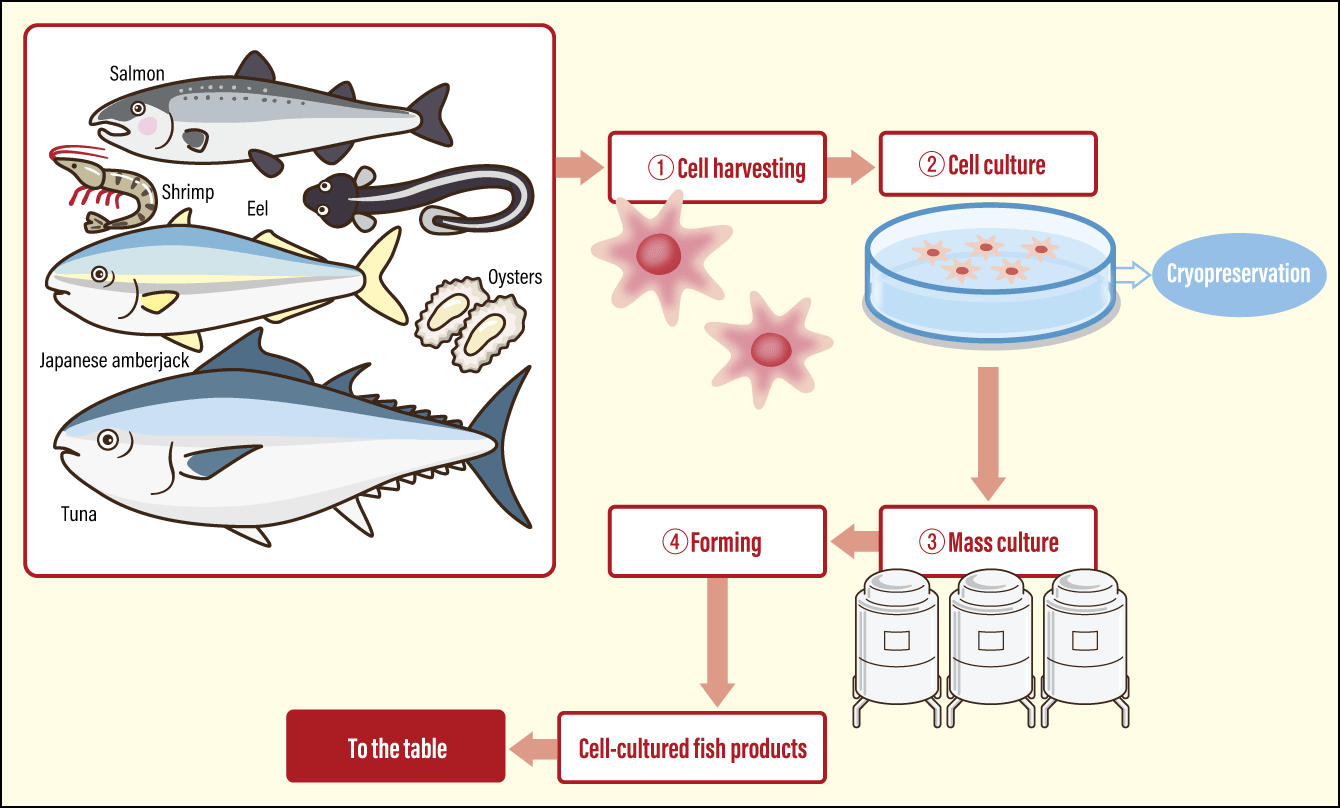

The technologies and culture processes used are basically the same as those employed to produce cultured meat from the cells of livestock (Figure 1). The seed cells are obtained from the flesh of live fish. These are placed into a culture medium and fed cell culture broth to make the cells multiply, producing fish flesh.

Figure 1. The process of manufacturing cell-cultured fish① Cells are harvested from live fish, ② then the cells are cultured. Cryopreservation is also possible. ③ The cultured cells are then cultured en masse, and subsequently ④ formed according to their intended purpose, such as fillets.

The cell-cultured fish produced in this way can easily be processed to surimi (fish paste), which can be used for products such as kamaboko (fish cake). The key challenges that need to be addressed to achieve commercialization are mass production and cost reductions. However, when it comes to fish fillets and thick blocks of sashimi, it is necessary to form the cell-cultured fish into chunks with the appropriate texture. It is very difficult to do this with simple culture technology.

Fish flesh includes both muscle and fat. It is not an easy task to form cell-cultured fish in a way that satisfies people’s expectations, in terms of appearance, texture, and taste. It would be all the more difficult to culture an entire fish from head to tail. As such, cellular aquaculture as a food production method involves culturing cells to produce the tastiest parts from the fish we want to eat.

So, how did this scientific production method come to be developed? As you all know, the fish and shellfish that reach our dinner tables can be divided into wild seafood and farmed seafood. However, relying on these existing production methods alone might result in shortages of such food in the future. Factors behind this issue include the growing world population and increased demand for food, and the decline in resources due to environmental problems such as climate change.

The first time I heard about cellular aquaculture, I thought of it as a new scientific method of food production, or one more option in addition to fishing and aquaculture. While I myself saw it as a positive development, the acceptance of new things by society often entails a degree of friction.

Using cell culture to produce fillets of Japanese amberjack and salmon

I undertake various activities relating to fish cuisine and the fisheries industry, and also lecture on fish-related food culture as a visiting lecturer at my alma mater, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology. I am neither a scientist nor a cellular aquaculture researcher. However, I believe that this new production technology involving cell culture will be needed both by our fish-centered culinary culture and the fisheries industry. Accordingly, I provide information and spread the word about cellular aquaculture to a variety of people from those involved in the production and distribution to consumers, in an effort to promote understanding and to popularize this technology. This is why I want to tell people in the fisheries industry that cellular aquaculture is not in conflict with the existing fishing industry, and to the consumers that it gives us an additional source for tasty fish. With this in mind, I am working to disseminate information that will ensure cellular aquaculture is accepted by society, without prejudice or preconceptions.

But right now, before we have reached the stage of conflict with the existing fisheries industry about which I had been worrying, the situation is that neither fisheries producers nor the public as a whole are familiar with cellular aquaculture as a concept.

So far, the biggest impact in Japan came in January 2022, when it was reported that the company operating a major Japanese conveyor belt sushi chain had entered into a business tie-up with a U.S. startup that had used cell culture to develop fillets of Japanese amberjack. I myself received a number of requests from the media to comment on this development.

In fact, looking at the global perspective, there are countries where research and development focused on cell-cultured fish are more advanced than Japan. While the technology is still under consideration in Japan, scientists overseas have already developed Japanese amberjack and salmon fillets, and held tasting sessions for dishes made with these fillets. In Singapore, which is the only country in the world to have established regulations concerning cultured meat and to permit its sale, there are companies working on setting up sales and production systems. Competition to commercialize such products is heating up. For example, the U.S. startup mentioned above used a 3D food printer to process cell-cultured Japanese amberjack into fillets. Often encountered as sashimi and as a topping for sushi, Japanese amberjack is generally regarded as a typical part of Japanese cuisine. However, the species is very popular in the West as well, particularly in the U.S. A distribution network has been put in place, via which farmed Japanese amberjack is exported from Japan. One reason why this market has developed may well be consumers’ appreciation for the flavor of this fat-rich fish.

While Japan tends to be the first place to spring to mind when one thinks of a fish-centered food culture and fish-loving countries, this example of Japanese amberjack demonstrates that it is far from the only one. Various companies overseas are competing to develop and commercialize cell-cultured seafood. Attempts are being made to culture a truly diverse array of species other than Japanese amberjack, including salmon, shrimp, tuna, and oysters (Figure 2). One could probably say that the global trend in cellular aquaculture is to culture the fish and shellfish that consumers worldwide enjoy eating.

Photograph: imagebroker/Aflo

Photograph: imagebroker/Aflo

Figure 2. Example of an experiment involving cell-cultured fish: salmonA pack of frozen lab-cultured salmon.

Cellular aquaculture complements the fishing and aquaculture industries

It is hoped that cellular aquaculture could be used to avoid the problems and resolve the challenges currently faced by the fisheries industry. One example is the stewardship of resources.

Catches of Japanese eel have plummeted in recent years, with stocks in danger of depletion. Accordingly, resource stewardship efforts are focused on restricting the quantity of fry (glass eels) caught for aquaculture and refraining from catching Japanese eels heading to spawn. If cell culture could be used for fish species that are difficult to farm and those whose numbers are declining, such as Japanese eels, it would be possible to produce food without reducing the populations of those species. In fact, there are universities in Japan that are working on basic research focused on cell culture of Japanese eels.

I hold seminars about the latest trends in cellular aquaculture. The one I organized at the end of last year featured as guest speaker Mayu Sugisaki, a board member of an organization called Cellular Agriculture Institute of the Commons, who works for an Israeli company developing cultured eel meat. At the symposium, Sugisaki commented that cellular aquaculture will likely be an effective production method from the perspective of the stewardship of resources.

As cultured cells can be preserved by freezing (cryopreservation), she said, it is possible to create products by allowing cryopreserved cells to multiply, rather than going through the process of catching individual fish and harvesting their cells each time. Consequently, it is not necessary to sacrifice a large number of live organisms for the purposes of cell culture. This means that we will be able to keep cells in stock and let them multiply without reducing the size of the population.

However, to avoid misunderstanding, I should note that this approach adopted in cellular aquaculture is not intended as a rejection of the fishing and aquaculture industries. As each has their own advantages and disadvantages, the existing fisheries industry and the cellular aquaculture of the future will complement each other.

Hopes are growing for the development of cellular aquaculture, as a solution to protect food resources and the environment alike. At the same time, issues that need to be resolved are also emerging. In my view, there are three major challenges to be overcome in order to commercialize cellular aquaculture.

The first is reducing costs. Currently, producing fish by means of cell culture involves quite considerable costs, as it requires expensive cell culture broth and other inputs. The key question will be how to scale up production from the research level to a commercial level at which mass production is possible.

The second is rulemaking. Once progress toward commercialization has gained momentum through cost reductions, rules aimed at the popularization of cellular aquaculture will be needed. However, Japan does not currently have any laws or regulations focused on foods produced by means of cell culture. Accordingly, at the end of last year, the Cellular Agriculture Study Group submitted to the government a set of recommendations it had compiled regarding the safety and food labeling rules that will need to be put in place to popularize the technology. I myself am involved in this initiative.

And regarding the third, I think naming is crucial. There is a foodstuff that has the same appearance and texture as crab meat: kanikama crab sticks. The Japanese name accurately conveys the information that it is a food resembling crab (kani in Japanese) made from kamaboko. This hit product is now hugely popular both within Japan and overseas, and one reason why it has been so widely accepted may well be the effectiveness of its name. While products of culturing cells from livestock such as cows, pigs, and chickens are referred to as cultured meat, and that from fish as cell-cultured fish, I hope that good names for these foods will be devised in due course.

Chicken nuggets made from cultured meat have been on sale in Singapore since 2020. A German cell-cultured seafood company has disclosed plans to follow in the footsteps of this development by bringing its product to market by the end of 2023 in Singapore. While cellular aquaculture is still unfamiliar to most, such moves seem likely to grow both within Japan and overseas.

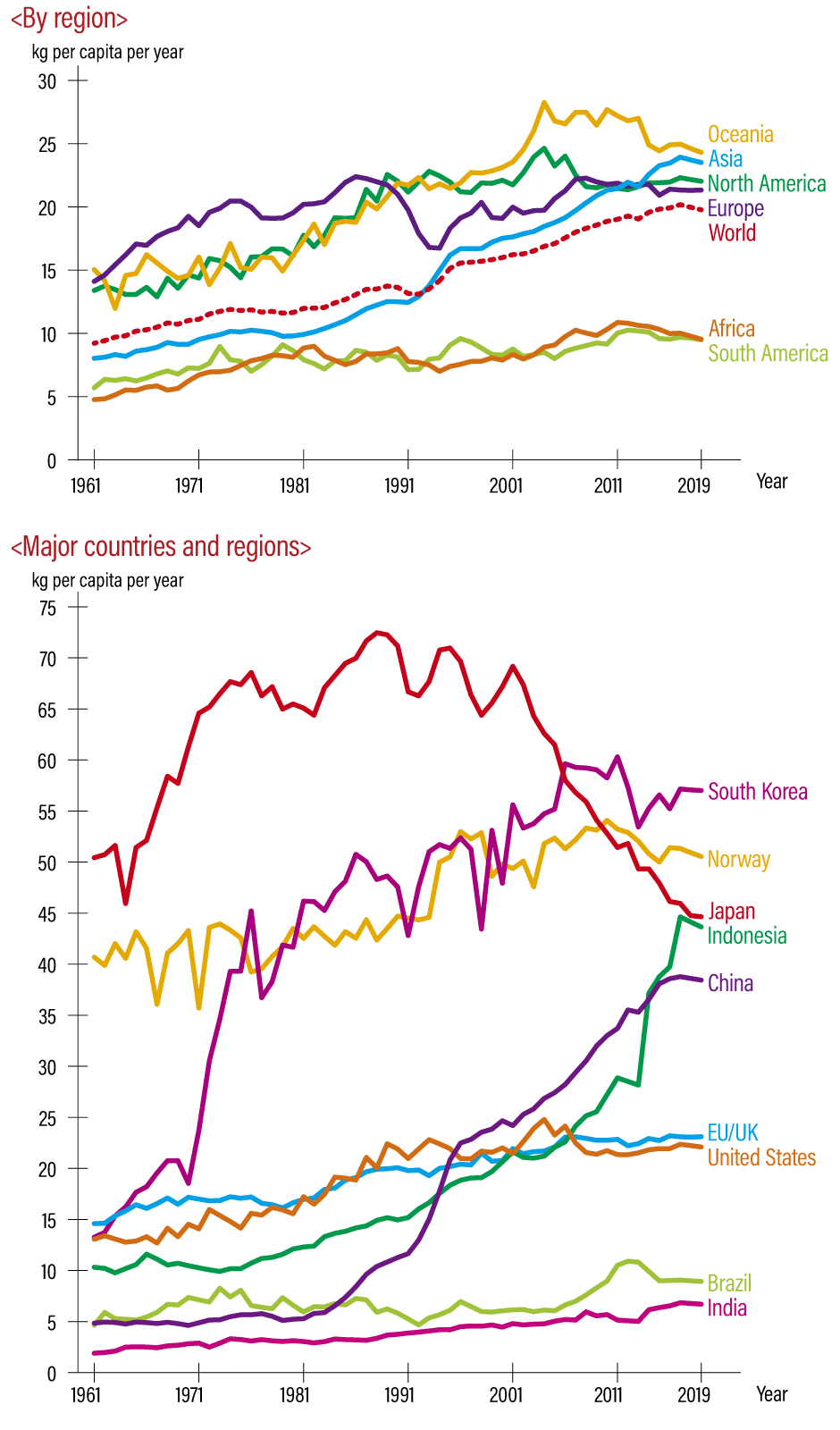

Global fish consumption

Behind the need to develop cellular aquaculture are the decline in global fish catches and the expansion in the quantity consumed in inverse proportion to this fall. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), while the total combined output of the world’s fishing and aquaculture industries is continuing to grow, the percentage of stocks fished at sustainable levels is on the decline. The White Paper on Fisheries published annually by Japan’s Fisheries Agency states that annual per-capita consumption of fish and fishery products for human consumption in Japan is trending below the level seen about 50 years ago, while the figure has, conversely, roughly doubled worldwide over the last 50 years. Factors behind this include the internationalization of food distribution due to advances in transportation technology and changing diets in developing countries due to economic development, particularly in emerging countries, where there has been a shift away from traditional diets centered on potatoes and cereals toward protein-rich diets containing a great deal of meat and fish. Most notable has been the marked rise in the consumption of fish and fishery products in Asia, where fish-eating was already customary, with consumption roughly octupling in China and quadrupling in Indonesia over the last half-century. Increases in the world’s population have also had a major impact. On November 15, 2022, the global population hit the 8 billion mark. The United Nations publishes projections of the world’s population every two years; the World Population Prospects 2022 forecasts that the world’s population will increase to 8.5 billion in 2030 and 9.7 billion in 2050. Growth in global demand for marine produce therefore looks set to continue rising as the world’s population increases.

Sources: FAOSTAT (Food Balance Sheets) (FAO) (other than Japan) and Food Balance Sheet (The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries) (Japan)

Sources: FAOSTAT (Food Balance Sheets) (FAO) (other than Japan) and Food Balance Sheet (The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries) (Japan)Figure 3. Trends in the world’s annual per-capita consumption of fish and fishery products as foodThe top diagram shows that global per capita consumption of fish and fishery products has roughly doubled over the last half-century. The bottom diagram shows the growth in consumption in emerging economies.