Scientists now understand that nutrition in childhood and at each life stage thereafter affects health in adulthood. From adolescence, changing our diet and habits in response to changes in our own awareness can lead to improved nutritional status. However, to improve children’s nutritional status, especially in early childhood, both the child’s relationships with their caregivers and the provision of a suitable environment around them are important. The knowledge required to systematically consider children’s nutrition is steadily being assembled, including such extremely contemporary issues as children’s screen time and the new perspective of dietary diversity.

Special Feature 1 – Children’s Nutrition Nutrition in childhood has a lifelong impact

composition by Rie Iizuka

There is growing recognition of the importance of understanding and appropriately addressing the distinctive nutritional issues at each stage of our lives. This is because we have come to understand that malnutrition at one stage can have a major impact on the subsequent course of a person’s life. In the case of children who were low–birthweight infants, we know that failure to improve malnutrition resulting from sustained inappropriate breastfeeding and diet in childhood can lead to chronic malnutrition and even affect intellectual potential. There are also reports that thin mothers are more prone to delivering babies with a low birthweight. It is becoming apparent that nutritional status in childhood has a lifelong impact, with some researchers highlighting the possibility that poor fetal nutrition could raise the risk of developing lifestyle-related diseases in adulthood.

Lack of guidelines for early childhood

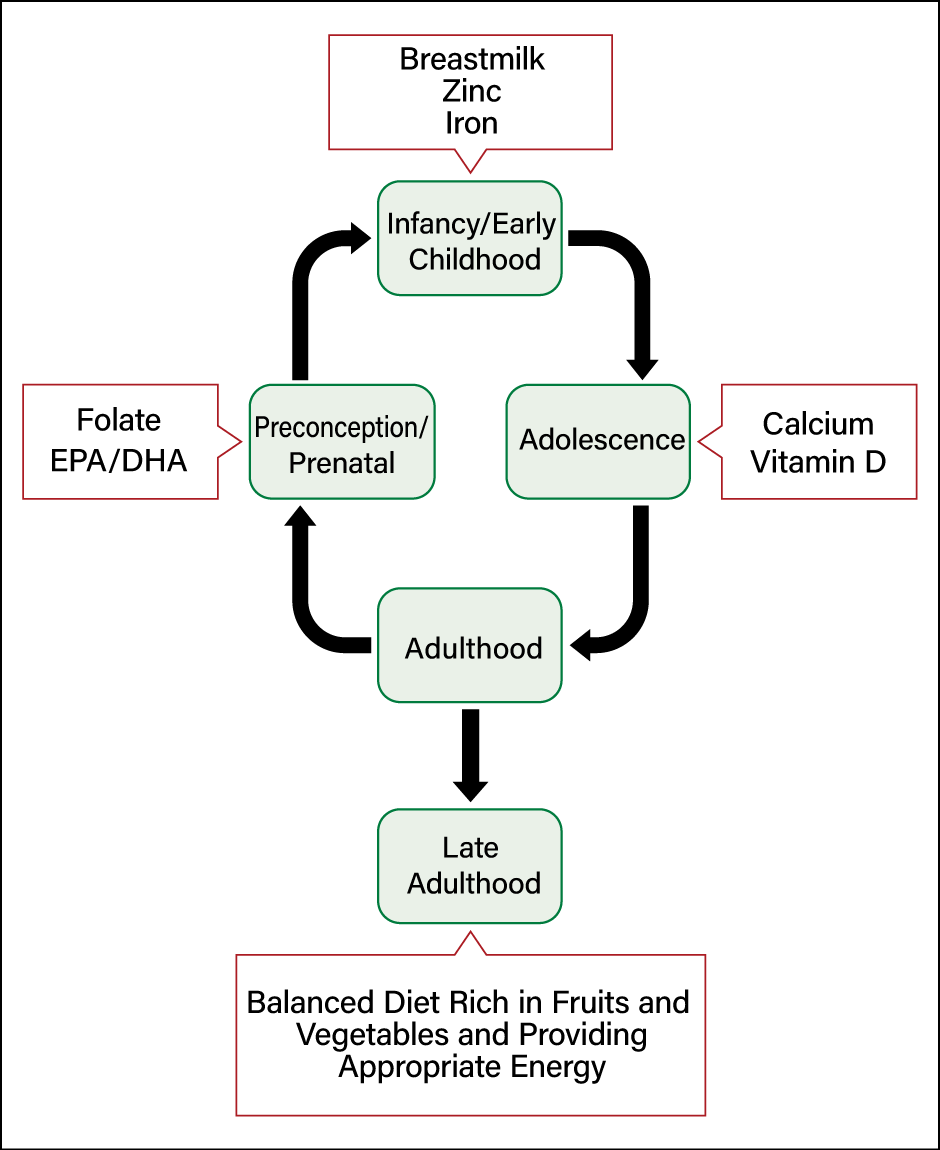

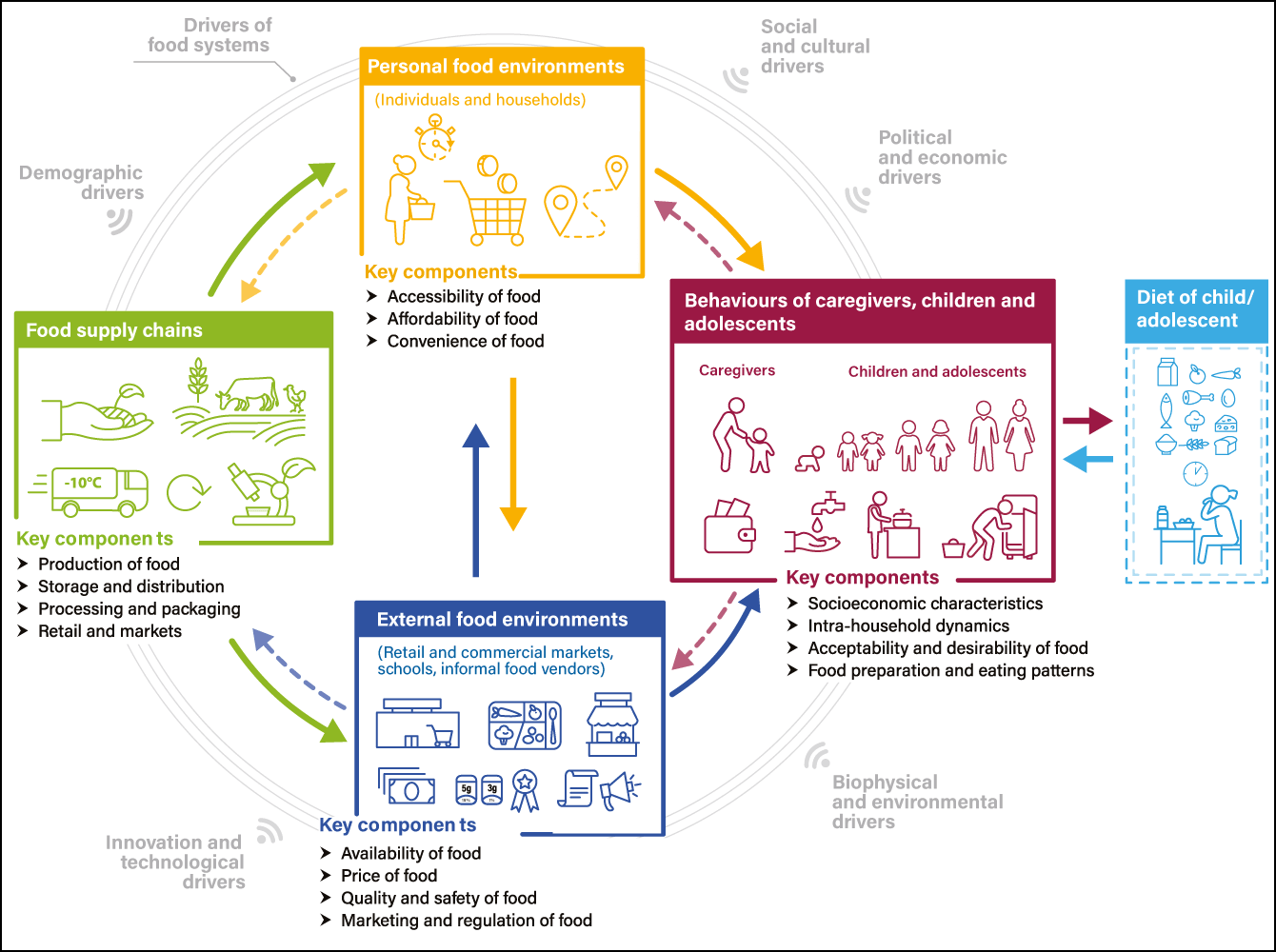

Diverse factors influence nutritional status across the life course from the preconception/prenatal period right through into adulthood, including biological and physical factors, social behavior, and experiences in daily life. Continued across the life course, poor nutritional status may affect an individual’s health and may even cause intergenerational health disparities at the community level. Accordingly, it is important to identify diets that affect children’s nutritional status (Figure 1).

Herman DR, Baer MT, Adams E, et al. Life course perspective:

Herman DR, Baer MT, Adams E, et al. Life course perspective: Evidence for the role of nutrition, Matern Child Health J, 18:450-461, 2014

Figure 1. Examples of key foods/nutrients affecting critical periodsLooking at human life divided into the five stages of infancy and early childhood, adolescence, adulthood, late adulthood, and preconception/prenatal, one can see that each has key nutritional issues. Appropriate interventions in this regard are thought likely to assist in fostering dietary intake and promoting health.

Among the initiatives aimed at providing lifelong nutritional support in Japan are Healthy Parents and Children 21, which focuses on the health of mothers and children, and the Health Japan 21 National Health Promotion Movement. Other health programs offering such support include the Maternal and Child Health Handbook, health checkups for expectant mothers, for children at 18 months and three years old, health checkups at school and school lunches. There are guidelines for expectant and nursing mothers, guidelines on breastfeeding and weaning, dietary guidelines, support booklets, and the Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese. However, one clear omission from this raft of measures is a set of guidelines offering support during early childhood.

While it is true there are guidelines for such matters as the meals provided at nursery schools, these are not aimed at children’s caregivers, nor has any direction been set out regarding support for matters other than diet. Everyone in the field of nutrition agrees it is crucial to ensure seamless interventions in children’s nutrition from the prenatal period onward. Accordingly, a research team of which I am a member is currently involved in work to draw up guidelines for early childhood.

Compared with other countries, there is little research into children’s nutrition in Japan. One reason for this could be the fact that, fortunately, only a small proportion of children fall outside the growth curve; that is to say, few children are excessively thin or fat. Adult obesity is a major problem, as it is linked to lifestyle-related diseases, driving up medical care costs. Since FY2015, the proportion of children inclined to obesity has been tracking at 2-3% among preschoolers and 10-11% among children of school age. Support providers regard those levels as manageable among the children whom they oversee.

A growing number of children have obese tendencies.

However, a change in children’s physiques was observed in the recent report on the FY2020 School Health Examination Survey.

In every age group, the proportion of children with obese tendencies had risen since the previous year, with 13.31% of 11-year-old boys having obese tendencies. This is the result of the unusual environment brought about amid the COVID-19 pandemic, with people’s behavior and lifestyles thought likely to have changed due to such factors as the halting of lunches at nursery schools and the increased frequency of teleworking among caregivers. The number of children with obese tendencies is also known to have increased after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima nuclear accident. Given these lifestyle changes and this social situation, those working in this field will be keeping a close eye on the survey results for next year and beyond.

While one can imagine that the pandemic has made life difficult by limiting school activities, it is not clear what kind of diet amid this situation leads to obesity among children. Alternatively, a lack of exercise or excessive intake of snacks could be behind the figures. When considering support for healthy growth and development, one can imagine that guidance concerning dietary content is not sufficient on its own. A 2019 document published by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) lists the environmental factors influencing children’s diets (Figure 2).

UNICEF, The Innocenti Framework on Food Systems for Children and Adolescents,

UNICEF, The Innocenti Framework on Food Systems for Children and Adolescents,The State of the World’s Children 2019: Children, food and nutrition, P56

Figure 2. The Innocenti Framework on food systems for children and adolescentsEven if it is only the content of the diet that directly affects children’s nutrition, dietary content itself is considerably influenced by the indirect environment around them.

First, looking at the household dynamics of cooking and eating food kept in the home, the quality of the diet provided to children differs according to the foods accessible to the household. While the impact of the economic situation is easy to understand, the quality of diet is influenced by the kinds of products sold in nearby supermarkets, whether those foods are safe and affordable. In addition, the foods sold in retail outlets are affected by the food system in terms of whether they are hygienically produced and processed. Furthermore, children’s diets are affected considerably by the environment around them, including the kind of menus provided at childcare facilities such as nursery schools and centers for early childhood education and care, the ways in which those menus are provided, and the extent to which nursery teachers at those facilities understand nutrition. The right surrounding conditions must be put in place to ensure the provision of a food environment conducive to the healthy growth of infants and young children.

Two keywords have recently come to be mentioned frequently in the context of the environment around children’s nutrition. One is dietary diversity.

Until now, advice about the importance of eating a well-balanced diet has been tailored to age, with a primary focus on adults and seniors. In contrast, reminders concerning preschoolers and schoolchildren have merely highlighted the importance of breastfeeding and warned about the need to consume iron and calcium, as nutrients prone to be lacking in children’s diets. This left us with the question of how to think about what constitutes a well-balanced diet in early childhood.

Over the last few years, international organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO), and UNICEF have frequently and in unison highlighted the importance for children of dietary diversity —— that is to say, providing children with experience of eating diverse foods.

Worldwide, a shared recognition is emerging of how important it is to provide children with experience of eating diverse foods, in order to maximize their potential. This means creating opportunities where one thinks the child might try a food, even if it is a food they normally reject or one that the caregiver themselves dislikes. The hypotheses behind this advice include that it might ultimately lead to the child developing a good nutritional balance, and that children eating such a diverse array of foods might mostly take care of a good nutritional balance once they choose their own diets as adults.

So, how can we encourage children to eat a diverse diet?

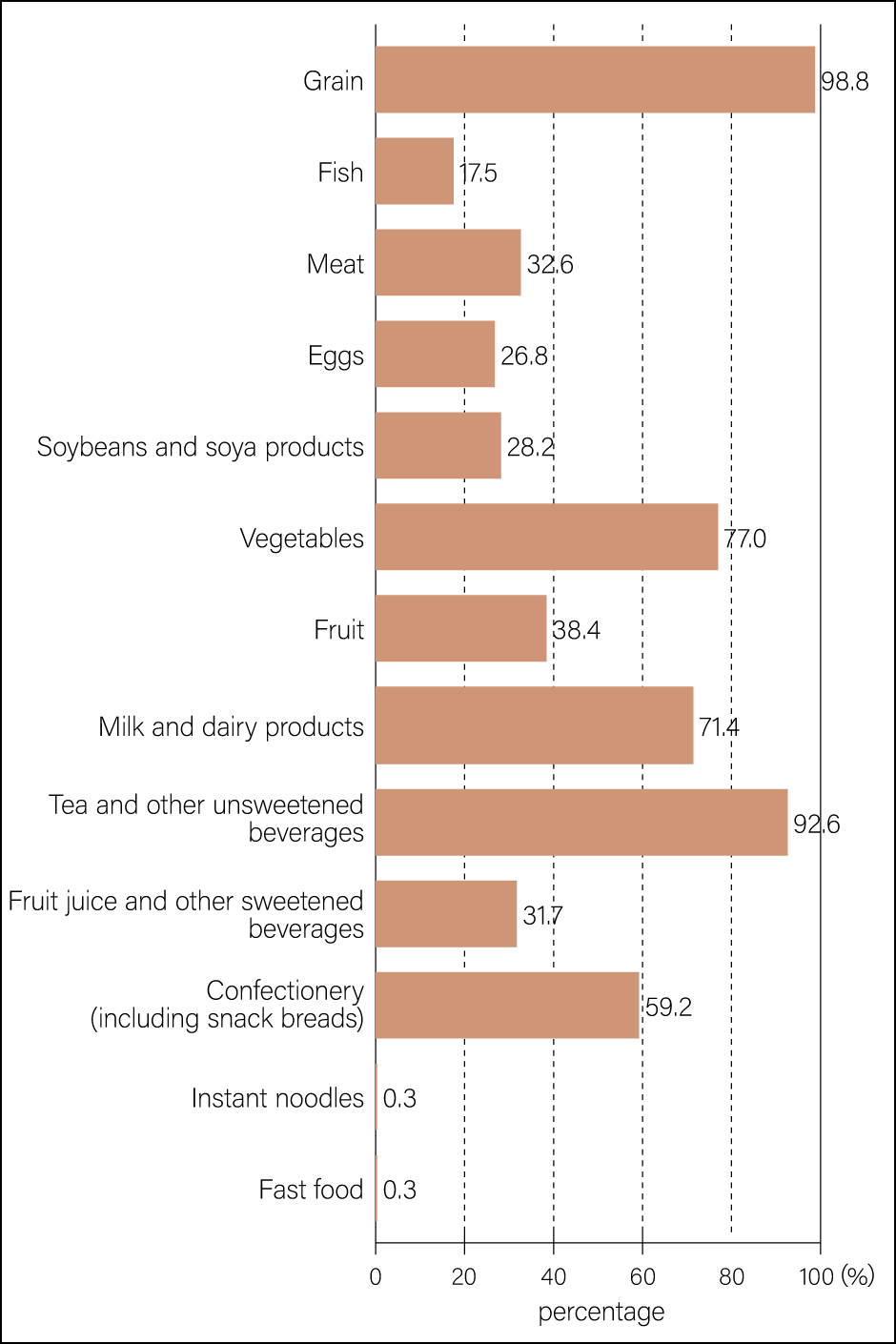

Looking at the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) FY2015 National Nutrition Survey on Preschool Children, we can see which foods children aged between 2 and 6 eat at least once a day (Figure 3). From this we can see that, while 98.8% eat grains at least once a day, the overall number of foods consumed tends to be low. Perhaps because the information that vegetables and unsweetened beverages are preferable for a healthy diet have permeated among caregivers, one can see that a high proportion of children consume foods of this nature once a day. Meat, fish, and eggs are also important sources of nutrients, but from this one can see that caregivers have a strong desire to ensure that children eat vegetables.

Cited from the Report on the National Nutrition Survey on Preschool Children FY2015

Cited from the Report on the National Nutrition Survey on Preschool Children FY2015(survey of children aged between 2 and 6 years old)

Figure 3. Share of foods consumed at least once a day by food groupThe proportion eating vegetables at least once a day is unexpectedly high, but on the other hand, one can see an imbalance in the number of foods.

Wanting to learn more about children’s dietary diversity and the factors therein, I myself am conducting research on the topics of children’s diets and lifestyles. Using the aforementioned MHLW data, I assign a score for the number of foods per day up to a maximum of 8 points, placing those scoring 3 or less in the lower food diversity group and those with a score of 4 or more in the higher food diversity group. Analysis of this data and the relationship to lifestyle and home environment has revealed a number of factors that appear to be related to dietary diversity.

First, it seems that children from economically better-off households often eat a diverse diet. While this is easy to understand, the other point to which I wish to draw attention is screen time —— that is to say, the time spent watching TV or videos, or playing screen-based games. A strong relationship between children’s dietary diversity and screen time has been reported from studies not only in Japan, but also in a number of other countries. In Japan, many of the children with a dietary diversity score of 3 or less on both weekdays and weekends fall into the group with two or more hours of screen time per day. Another finding is that many Japanese children with low dietary diversity eat fast food and instant noodles.

Circadian rhythms are related to dietary diversity

As children are affected not only by their own behavior, but also by that of cohabiting family members and others around them, I analyzed the matters to which caregivers pay attention in relation to dietary diversity.

As a result, I found that the children of caregivers who reported paying attention to nutritional balance had higher dietary diversity. In addition, where caregivers paid attention to the content of snacks, their children consumed foods that they were unable to fully include in the three main meals of the day. As young children can only eat a small amount of food at a time, snacks need to be skillfully used to increase their dietary diversity. Diversity can be increased by devising such simple strategies as providing yogurt, rather than always offering sweet confectionery as snacks.

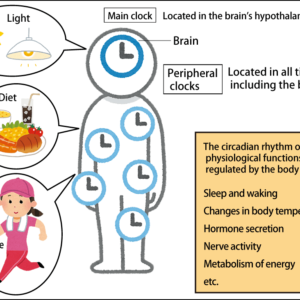

One interesting finding is that dietary diversity was higher among children where their caregivers paid attention to regular mealtimes. While the childcare and nutritional guidance provided in health checkups for infants and young children has long included advice to ensure children eat meals at set times to regulate their circadian rhythms, the discovery of a link between circadian rhythms and dietary diversity is new. My own hypothesis is that screentime might well be involved indirectly in that relationship.

Children’s nutritional status is affected by a combination of the relationship between the child and their caregivers, along with who is involved in that relationship and how —— that is to say, what do they do within the household —— coupled with the environment outside the home, including the retailers selling food, food manufacturers, and institutions such as nursery schools. Children who develop dietary diversity during this period will likely be able to maintain dietary diversity in adulthood. If children’s nutrition is substantially influenced by their caregivers, then the caregivers themselves will need to have experience of encountering a diverse array of foods. I believe it will be necessary to provide support from childhood, to ensure children grow up to become such caregivers.

There are aspects of children’s nutrition that are difficult to study, due to overlapping ethical considerations. However, if we can conduct adequate research as understanding of the necessity progresses, we will be able to explore the features that nutrition in early childhood has in common with adolescent nutrition. And if we do that, I believe it will further enhance support for nutrition across the life course.