Japan is said to have low rates of adolescent obesity. One factor reportedly contributing to this is the school lunch program, which ensures that children all eat the same meals based on appropriate nutrition standards. Japan’s world-class school lunch program has long been the focus of attention, but there had been no large-scale epidemiological studies of its effects. However, the last few years have seen the publication of results from epidemiological research with a public health perspective, based on diverse big data amassed across society. So, what emerged from these results?

Special Feature 1 – Children’s Nutrition Revealed by big data!

Japanese school lunches reduce obesity

composition by Toshiko Mogi

Within the field of public health, my specialism is the evaluation from a medical perspective of systems and measures to support the health of the public within the context of health policy and economics. I use big data —— huge sets of diverse data amassed across society and made publicly available —— to conduct research aimed at providing the public with high-quality health care. One of the topics of my research is how Japan’s school lunch program affects children’s health.

Obesity is known to be an impediment to good health. Based on findings to date, researchers have pointed out that overweight (weighing above the normal range, but not being in the obesity range) and obesity in adolescence affects an individual’s future obesity and lifestyle-related diseases, as well as death rates due to such factors.

I myself am in practice as a clinical physician and mainly treat elderly patients. In the course of my clinical work, I sometimes get a very real sense that many of the factors influencing a person’s health in adulthood can be traced back to their childhood years. I wonder whether interventions during childhood might be useful in fundamentally improving health in adulthood.

Japan’s school lunch program is virtually unprecedented worldwide

In fact, overweight and obesity in children is a growing global problem, affecting not only developed countries, but also developing ones. However, despite this, Japan is widely renowned for having a lower rate of adolescent obesity than other countries. School lunches have been cited as a reason for this.

While South Korea and Taiwan have similar school lunch programs to Japan’s, there are hardly any other examples anywhere else in the world. For example, in advanced countries such as the U.S., cafeteria-style lunches that allow children to choose what they want to eat are the norm, and it is not unusual for them to make unhealthy choices. Against this background, attention has focused on the school lunch system in Japanese elementary and junior high schools, under which everyone eats the same meal designed to appropriate nutritional standards at lunchtime in schools.

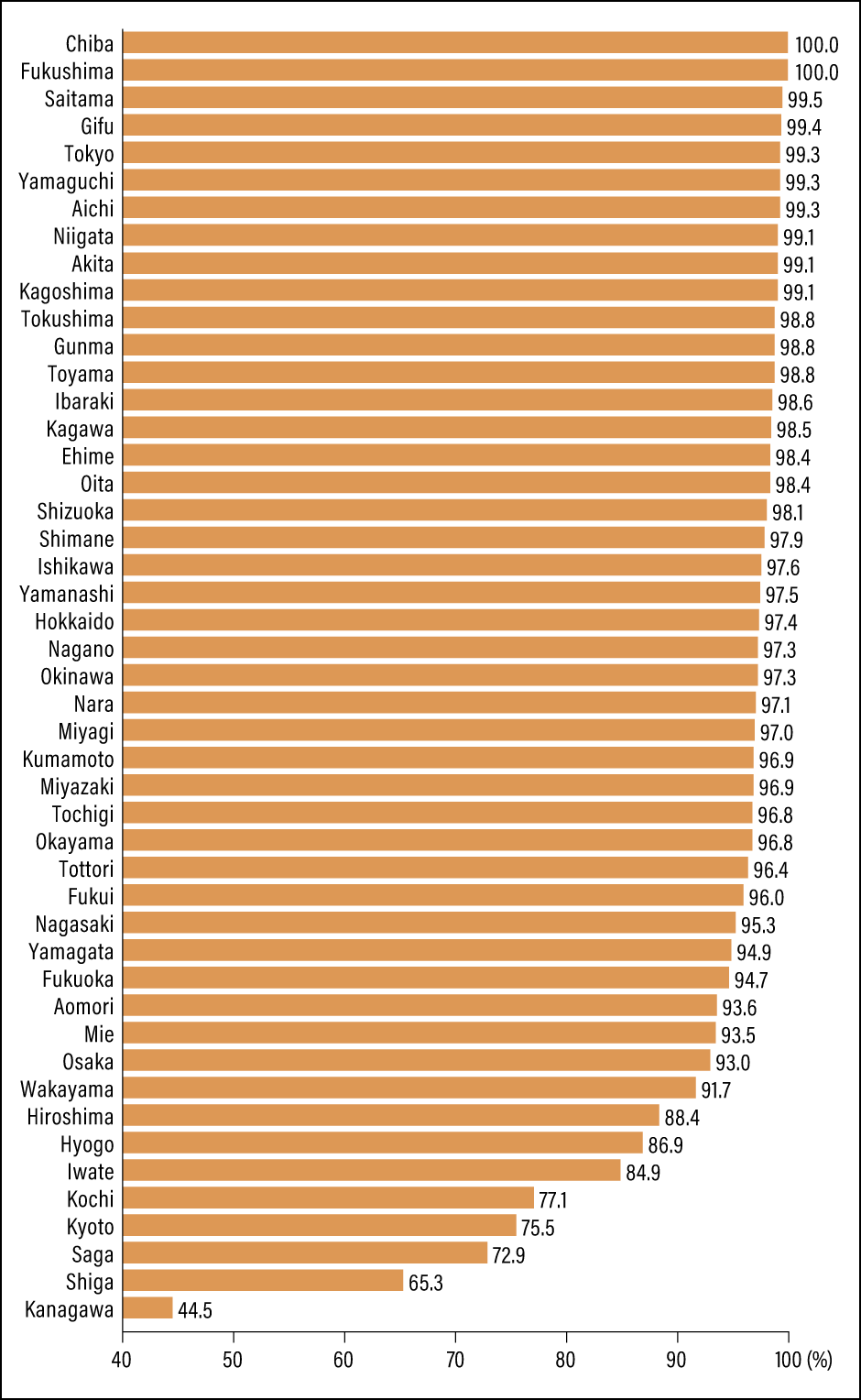

However, no evidence had been presented to show any relationship between Japan’s low rates of adolescent obesity and its school lunch program. Moreover, whereas a full meal service is provided in almost all elementary schools, with a national coverage rate of almost 100% and even the lowest prefectural rate being as high as 92.7%, there are major differences in school lunch coverage at the junior high school level (Figures 1 and 2). Accordingly, my research team investigated the relationship between the physical state of children in adolescence —— that is to say, junior high school students —— and school lunches.

Created from data in Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology,

Created from data in Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology,“FY2018 School Lunch Implementation Survey”

Figure 1. School lunch coverage by prefecture (public junior high schools)We listed the school lunch (full meal service) coverage at public junior high schools by prefecture. Chiba and Fukushima prefectures come out on top, with 100% coverage, while most others are above 90%, but there is a big gap between them and Kanagawa Prefecture, which has the lowest rate, at 44.5%.

photoAC

photoAC

Figure 2. Examples of school lunchesWhile there may be some differences between generations and the regions in which people grew up, most Japanese people share a standard impression of what a school lunch looks like. However, the provision of lunches in this form is without precedent in other countries (top: ground meat cutlet set meal; bottom: grilled fish set meal).

Our article on the study, “Impact of the school lunch program on overweight and obesity among junior high school students: a nationwide study in Japan,” was published in 2019 in the Journal of Public Health, an academic journal published by Oxford University Press. The full article can be read online, so I would just like to provide a simple outline of our findings here.

For our research, we used government statistics in the form of data from the School Lunch Implementation Survey and School Health Examination Survey conducted by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) between 2006 and 2015. We extracted an indicator from prefectural school lunch coverage rates in the form of the percentage of students who eat school lunches. This is because, as stated above, whereas the coverage rate at elementary schools is almost 100% nationwide, the coverage rate at junior high schools varies from one region to another.

From the School Health Examination Survey, we extracted a number of indicators of nutritional status by age and sex at the prefectural level, specifically mean height and weight, and the percentages of overweight, obese, and underweight children.

Then, using a technique called panel data analysis, we examined the relationship between prefectural school lunch coverage rates during the previous year and indicators of nutritional status the following year. In other words, we investigated the causal relationship between them, to see how the provision of school lunches was reflected in junior high school students’ nutritional status the following year.

We found that for each 10% increase in the prefectural school lunch coverage rate, the proportion of overweight boys fell by 0.37%, while the proportion of obese boys fell by 0.23%. As overweight and obese boys respectively account for approximately 10% and 5% of all male junior high school students, this means that the percentage of overweight boys decreased by about 4% over the course of a year, while the percentage of obese boys fell by about 5% over the same period.

While the figures for girls indicated a tendency for overweight and obesity to decrease, we did not obtain any statistically significant results. Studies such as the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s National Health and Nutrition Survey have shown a growing tendency for young Japanese women to be underweight. Consequently, we can surmise that the tendency of young women to restrict food intake also emerges among female junior high school students in this downward trend in overweight and obesity. Furthermore, no statistically significant effects on the percentage of underweight or mean weight or height were seen among either sex.

The results of this study demonstrate that, among boys at least, Japan’s school lunch program is effective in reducing overweight and obesity in adolescence.

In addition, looking at mean weight and height, there was a tendency for weight to decrease and height to increase in proportion to the rise in the school lunch coverage rate. From this, we can surmise that school lunches contribute to reducing overweight and obesity.

Consequently, we can say that the provision of school lunches at Japanese junior high schools was shown to be effective in reducing adolescent obesity at the group level.

Previous studies have highlighted the possibility that Japanese school lunches may increase the quality of children’s nutritional intake. However, this was the first study to use representative samples of adolescent schoolchildren to demonstrate the effectiveness of school lunches in actually reducing overweight and obesity.

Suspension of school lunches and its effects on physical status

Since 2020, the world has been beset by the COVID-19 pandemic. When the novel coronavirus outbreak first began to spread in Japan in March 2020, schools were closed en masse, with some shut for as long as three months or so. Naturally, provision of school lunches was also suspended during this time.

Attention focused on children for whom school lunches were a precious source of nutrient replenishment, with some people expressing concern about malnutrition among children. I, too, was worried about the effects that the suspension of school lunch provision due to school closures would have on children’s health.

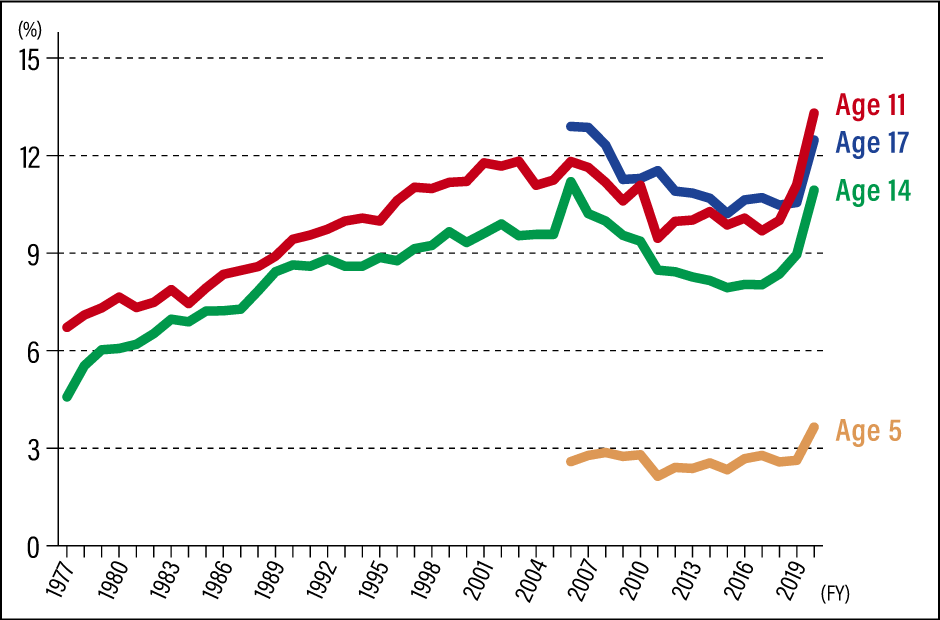

Accordingly, I checked the finalized figures for the FY2020 School Health Examination Survey published by MEXT in July 2021 and noticed that the percentage of children with obese tendencies had increased from the previous fiscal year (Figure 3).

Modified from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, “FY2020 School Health Examination Survey”

Modified from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, “FY2020 School Health Examination Survey”

Figure 3. Trends in the prevalence of children with obese tendencies by age (boys)Figures for all ages rose sharply in 2020, when the mass closure of schools took place.

While height and weight in general had increased, this is likely to be due to the fact that the pandemic caused a delay in children’s physical measurements being taken, among other factors. But why had the percentage of obese children of both sexes rebounded in all age groups? I do not have any properly researched findings, but my supposition from examining this data is that the causes include a fall in the quality of meals (particularly lunch), changes (increases) in meal size, and a lack of exercise.

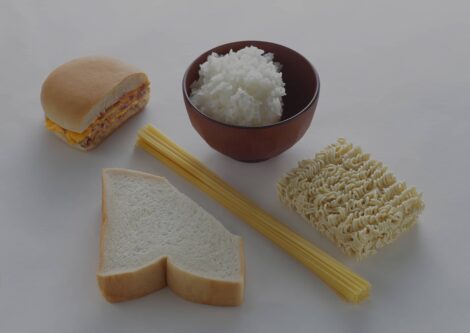

Immediately before the mass closure of schools and the declaration of a state of emergency, a social phenomenon occurred whereby shops sold out of instant noodles and cup noodles. It might be that people were hoarding them as a handy snack when they were feeling a little hungry or as a replacement for school lunches. Even if this is not the case, providing a lunch menu in the home that offers the abundant variety of foods meeting certain nutritional standards equivalent to the school lunch program is likely to be difficult. One cannot deny that this caused a decline in the quality of meals (in terms of nutritional balance, etc.)

When it comes to the quantity of food consumed, too, once lunch is over, children attending school do not snack until their classes finish for the day. However, when they are at home, they can keep snacking whenever they feel like it. Accordingly, this conceivably led to a rise in the quantity of food consumed. School closures will have resulted in a lack of exercise because of the elimination of opportunities for children to move around, including walking to and from school, taking physical education classes, and participating in extracurricular sporting activities.

On another occasion, I would like to study the effects of the presence or absence of a school lunch program on obesity and other aspects of children’s health. I expect that the relationship between school lunches and children’s health will become clearer if we examine the data in regions before and after the introduction of the full meal service at junior high schools.

The provision of school lunches is a local government service to citizens and a form of childcare support. To put it another way, it could be described as social expenditure for the sake of children’s health.

The availability of nursery schools has become a criterion for some families of an age to have young children when choosing the area where they want to live. I have also heard from people whose children took entrance examinations for private junior high schools that some junior high schools are promoting the fact that they offer school lunches and the shokuiku (food and dietary education) and health support aspects thereof in an effort to attract more applications. The availability of a full meal service might become a benchmark for assessing the level of services provided by a local government to residents of that area.

School lunches benefit all children’s health

I have been involved in research investigating the relationship between social expenditure for children and obesity in young children in countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). My article on this study, entitled “Relationships between social spending and childhood obesity in OECD countries: an ecological study,” was published in the British Medical Journal Open in 2021. This article, too, can be read in full online, so I will just provide a simple outline of our findings here.

We used data on social expenditure and educational finance indicators published for the 35 OECD countries between 2000 and 2015. The results of our study suggested that childhood obesity might be curbed by increasing social expenditure on children. In light of the effect of school lunches on curbing obesity in male junior high school students, we can judge that Japan’s school lunch program contributes to children’s health.

Incidentally, there is a term that has been bothering me of late: the buzzword “oya-gacha (parent lottery).” It means that it is only luck of the draw dictating the kind of parents to whom a child is born, and that a child’s chances in life are affected by their family environment. However, all children should, fundamentally speaking, be able to grow up healthy, and a variety of policies and support systems have been put in place to this end. The school lunch program is one such initiative. Further increases in school lunch coverage rates and improvements in the content of school lunches could be described as enhancements in support for children. I hope our research can be of some assistance in this regard.

It is thanks to the efforts of registered dietitians and others working on the front line that the school lunch program contributes to children’s health. I have been contacted by people involved with local government administration of school lunch programs, stating that they want to increase the budget for school lunches and asking whether I would allow them to use our article finding that school lunches curbed obesity in male junior high school students in their supporting documentation. Naturally, I agreed readily. The academic field of public health aims to contribute to the health of the nation. Please do make use of the findings from our research.

The history of school lunches

Japan’s school lunch program is believed to have originated in 1889, when a private elementary school in the Yamagata Prefecture town of Tsuruoka (now Tsuruoka City) began providing lunch in the form of rice balls and grilled fish to children from impoverished households. In 1932, the national government began to provide financial support for such programs, and they spread across the country. However, school lunch programs were suspended due to World War II. They resumed after the war, with the primary objective of improving nutrition among schoolchildren.

Laws relating to school lunches

School lunches today are provided in accordance with the School Lunch Program Act, which was enacted in 1954. Over the years, this law has undergone both wide-ranging revisions and minor amendments as needed in response to social changes. Most recently, partial amendments to reflect changes in reference intakes, including reductions in salt and increases in iron and dietary fiber intakes, entered into force on April 1, 2021.

School lunch coverage rates

According to the FY2018 School Lunch Implementation Survey published by MEXT in 2019, 93.5% of Japan’s 30,092 national, public, and private schools provided lunch in the form of a full meal service. Looking at the breakdown, the figure was 98.5% for elementary schools and 86.6% for junior high schools, which represented an increase in the percentage of junior high schools providing such lunches since the last time the survey was conducted (FY2016).

Types of school lunch

Depending on their content, school lunches are divided into “full meal service,” “supplementary meal service,” and “milk-only lunches.” The full meal service consists of a main dish, side dishes, and milk. The supplementary meal service consists of milk and side dishes, while milk-only lunches, as the name suggests, consist solely of milk. Including supplementary meal service and milk-only lunches, the school lunch coverage rate is 99.1% at elementary schools and 89.9% at junior high schools (FY2018 survey).