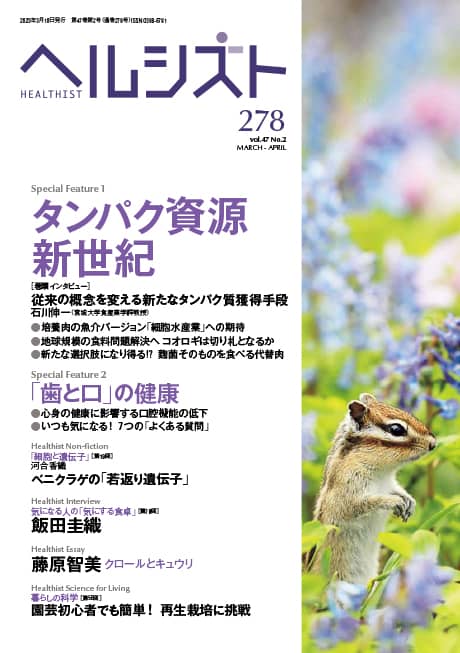

Along with cultured meat, which is produced by culturing meat cells, meat alternatives made from materials other than meat are attracting attention as new sources of protein. Meat alternatives are currently made from legumes, but using food crops of this kind has an impact on the environment. What might offer a solution to this issue is a source of protein called mycoprotein, which is made from a fungus. It differs from conventional meat alternatives in that the microorganism itself is consumed as a food. This raises hopes that koji (Aspergillus oryzae) —— a mold cultivated in Japan since ancient times —— has the potential to become a meat alternative.

Special Feature 1 – The New Era of Protein Resources A new option on the horizon? Koji mold as a meat alternative

composition by Rie Iizuka

illustration by Koji Kominato

It is estimated that the world will face a protein supply shortage by 2030, so work to develop meat alternatives as a substitute for meat from livestock is progressing in a number of countries. Factors behind this situation include population growth, changes in the supply and demand balance due to greater consumption of meat from livestock, as well as concerns about greenhouse gas emissions from industrial livestock farming and the limited availability of resources such as water and land. Various countries are competing against each other to develop such products, with estimates suggesting that the Japanese market for meat alternatives will grow from ¥3.17 billion in 2020 to ¥67.70 billion in 2030.

Meat alternatives made from koji mold

Most of the meat alternatives currently on the market are made from legumes, primarily soybeans. However, as legumes are themselves an agricultural crop, they entail a number of issues, such as the need for extensive agricultural land and water supply, their distinctive flavor, and the problem of allergies. Accordingly, we have recently embarked on the production of protein using microorganisms.

There are two ways of producing protein from microorganisms: a technique called precision fermentation, which involves getting microorganisms to produce a particular protein; and a method known as biomass fermentation, in which fungi are cultivated and produced as a protein in their own right. We are conducting development research focused on mycoprotein (the prefix “myco–” is derived from the Greek for fungus) by means of biomass fermentation using koji mold.

- * Biomass: The collective term for organic material from plants and animals, etc.

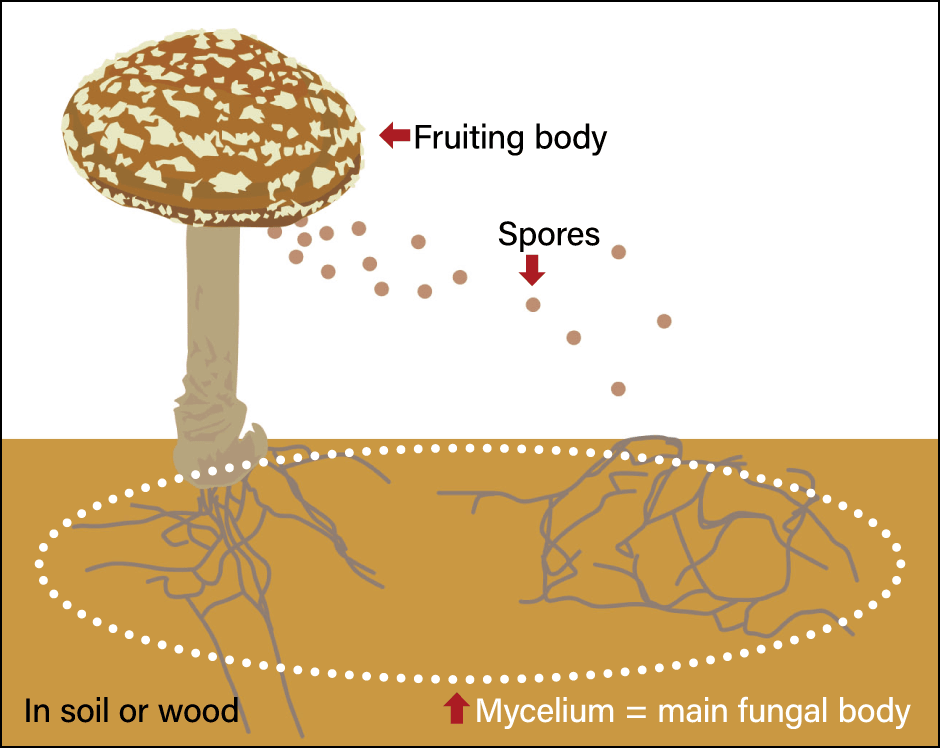

Mushrooms are an example of a fungus consumed as food, but the mushrooms that we eat are the fruiting bodies that form on top of the thread-like mycelium rather than the mycelium itself, which is the main body of the fungus and thus a different part from the fruiting bodies (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mycelium and fruiting bodyA mushroom is a structure produced by a fungus in order to form spores. The mycelium is an assembly of hyphae that constitutes the main body of filamentous fungi.

Our development work focuses on a meat alternative made solely from the mycelium of koji mold, which is a type of filamentous fungus; in other words, we are working on a new concept of establishing the koji mold microorganism as a food in its own right. Perhaps because microorganisms tend to be associated in our minds with mold and bacteria, people have never previously hit on the idea of eating them, but koji mold is actually an outstanding edible fungus.

Most of us will already have consumed koji mold mycelium. For example, take amazake, a traditional sweet, non-alcoholic drink made from fermented rice. When you drink it, you can sometimes feel little grains in the liquid; some of these are the remains of koji mold hyphae (fungal filaments) that became attached to the rice during its fermentation process.

Thus, koji is familiar to Japanese people, but koji mold and koji are, strictly speaking, completely different things. The terms rice koji (also known as malted rice) and soybean koji refer to foods produced by allowing koji mold to grow and ferment with rice or soybeans. In other words, the principal food here is the rice or soybeans, and when we talk about eating koji, we mean eating those staples rather than the mycelium itself. An example of a mycelium that is eaten is the Indonesian fermented food tempeh. When Rhizopus oligosporus spores are sprinkled over boiled or steamed beans and left to ferment, a solid mycelium will form after a day or so. In tempeh, too, beans make up the majority of the volume, but eating it involves consuming a lot more of the mycelium than in the case of koji.

We are developing a food that gives mycelium the starring role, unlike the fermented foods available until now.

We embarked on developing mycoprotein because it occurred to us that we might, as mycologists, be able to contribute to solving social issues. Broadly speaking, there are two reasons why we unhesitatingly settled on koji mold from the outset.

Findings and knowledge concerning abundantly available koji mold

One is the fact that it is used in existing foods, which is a very important point when developing not only mycoprotein, but any kind of meat alternative.

While people might be reluctant to eat fungi, many of the foods used in traditional Japanese cuisine —— including sakē, shochu liquor, miso, soy sauce, amazake, mirin, and vinegar —— are produced by means of microbe fermentation using koji mold, so one could rightly say that koji mold plays a major role in Japanese cuisine. People have the impression that koji mold is good for one’s health, and there is evidence of its effects on intestinal regulation. In Japan at least, it would be fair to say there is very little resistance to eating koji mold.

In addition, as a fungus already used in food, there is no need to start from scratch in terms of verifying the safety of koji mold.

The other reason is the fact that a huge stock of findings and knowledge concerning koji mold has been amassed, because it has been used for culinary purposes in Japan for more than 1,000 years.

Miso makers have replenished the seed miso —— miso starter, if you will —— in their storehouses since well before people became aware of the existence of microorganisms. In this process, microorganism strains that have mutated or caused an unpleasant flavor to develop cease to be used. It also results in the selection and preferential use of strains with a higher ability to decompose protein, producing umami or sweetness in the fermentation process. In the modern era, when the concept of microorganisms had made an appearance, people began to breed fungi and, once they had successfully domesticated koji mold, began to refine it.

Due to the presence of this fermentation industry in the background, most Japanese mycologists use koji mold as model fungus. Whole genome sequencing of koji mold was completed in 2005 and it became apparent that these fungi bred over the course of 1,000 years have evolved so that they do not produce toxins. Japan has an overwhelming abundance of knowledge concerning koji mold, including findings relating to enzymes and metabolism. Given its safety and ease of handling, I even feel that it is one of the world’s foremost microorganisms worth eating.

When commercializing meat alternatives, one also has to solve existing issues relating to farming and costs. Food production takes time: around five months to cultivate soybeans and as long as 26 months or so to raise cattle for beef, while even mushrooms take two months. Given the short production period of koji mold and speed at which the mycelium develops, it would be fair to say that it is a much more efficient food to produce. Even using our current method, koji mold can be collected within just a few days.

Furthermore, as shown in the table, a key feature of koji mold is that it has a very low environmental impact in comparison to conventional meat from livestock and even the soybeans used to produce meat alternatives.

| Grain (kg) | Water consumption (t) | |

| Beef | 11 | 20.6 |

| Pork | 7 | 5.9 |

| Chicken | 4 | 4.5 |

| Eggs | 3 | 3.2 |

| Soybeans | — | 2.5 |

| Koji mold | 0.4 | 0.1 |

Figures for koji mold are estimates based on the results of culture experiments.

While soybeans are one of the leading ingredients in meat alternatives, the varieties that can be used are limited and almost all are imported. Moreover, as soybeans are an agricultural crop and their growing use worldwide is driving up demand, a stable supply is not necessarily available. For Japanese people in particular, there is room for debate about whether the option of soy meat is even required, given our nation’s culture of eating soybeans in the form of tofu and natto (fermented soybeans) since ancient times.

However high the production efficiency and low the environmental impact of a food, it will not reach the bar required to be accepted as a meat alternative unless it is tasty and achieves a certain level of nutritional value.

With regard to these points, we have discovered that koji mold mycoprotein has roughly the same level of umami as kombu kelp and about the same amount of protein as beef.

Also contains vitamins

We believe koji mold mycoprotein bears comparison with other meat alternatives in terms of nutrition, as it contains non-negligible amounts of all 20 amino acids of which protein is composed. At the same time, fungi synthesize vitamins themselves, so their cells contain a certain amount. It would be fair to say that such differences from animal meat will be a positive advantage. What is more, koji mold mycoprotein contains ample amounts of the three components of umami. There is a possibility that the umami content is something unique to koji mold; if that turns out to be the case, the advantage of koji mold over other fungi as a meat alternative will likely grow further.

Allow me to outline the method we use to produce our meat alternative from fungi.

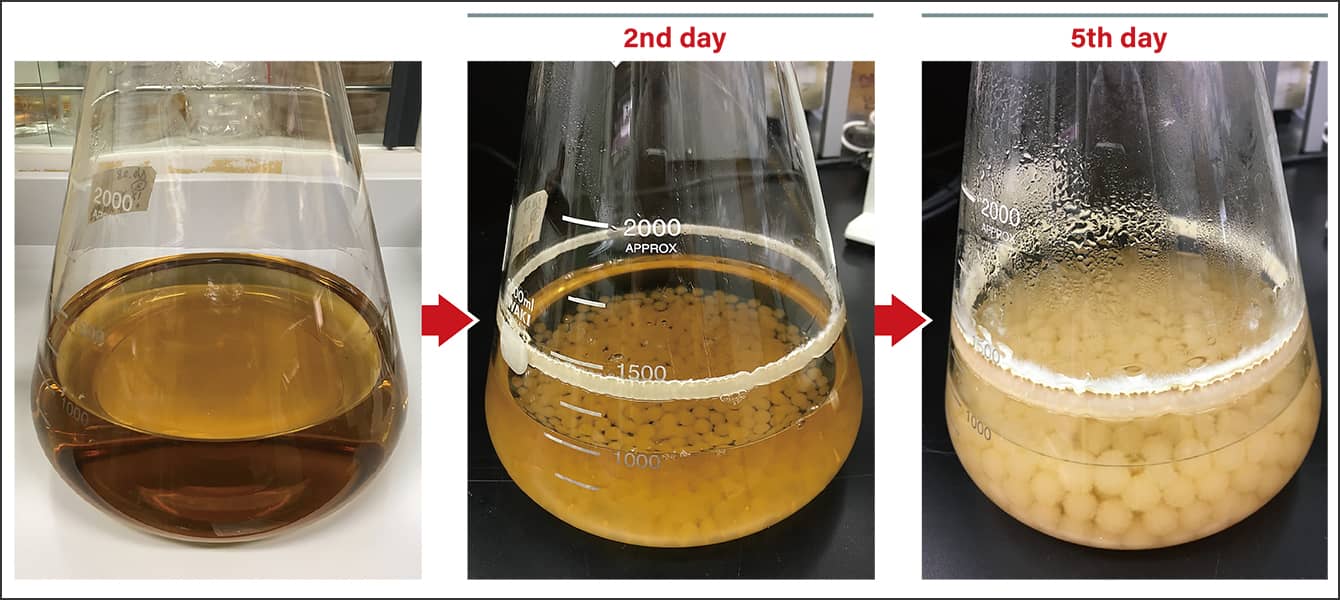

We culture koji mold from seeds called spores. We place the spores in a liquid culture medium and, while feeding them with nutrients, supply them with oxygen during shaking incubation, which causes the cells to grow and multiply (Figure 2). These form clusters big enough to see with the naked eye and grow into larger clumps that look like tapioca pearls. This is the state that the fungus reaches when it grows and swells after absorbing nutrients, but bacteria and yeast such as Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces respectively do not form such large clumps.

Figure 2. The process of manufacturing a meat alternative using koji moldLots of tapioca-like pearls form just five days after inoculation. These are collected and turned into “meat.”

If we gather up all these clumps and squeeze the water out of them, we can then process them for use as food; for example, we can use them like ground meat to make a burger. The manufacturing process is very simple.

Meat alternatives based on mycelium produced by biomass fermentation are a very similar concept to cellular agriculture, which involves culturing animal cells to make meat. The manufacturing process is simple, being based on culturing the fungus to make it multiply and collecting the results, and it requires similar techniques as processes based on cultivating better crops, including such considerations as how to make the fungus grow better, what to use to make it tastier, and what kind of fertilizing nutrients are appropriate.

The key to it all is the knowledge, technology, and strains of koji mold that have been built up, as I touched upon earlier.

Let us say that each koji starter maker in Japan has a stock of at least 1,000 strains of koji mold. As such, the existence of diverse strains of the fungus will be useful in breeding strains that can boost production efficiency when looking to commercialize the product in the future, and will also be very helpful when looking to design growing environments tailored to the purpose for which the mycelium will be used, such as when considering how to create a product with a more chicken-like flavor or how to produce a texture more like steak.

In addition, koji mold will grow on almost any culture medium. We not only use ordinary culture medium in our research, but also carry out development work using such food waste as the lees from brewing sakē, beer, and soy sauce, and also rice bran. While there are many other kinds of food residues that go unused, the only choices until now have been to use them as livestock feed or to dispose of them as industrial waste. However, livestock production may decrease in the future, which would reduce the options for using these residues and thus increase the volume of waste. We believe it would be better to use them as a culture medium for fungi, if they deliver good production efficiency.

What is more, we are starting to identify differences in the features of the end product depending on the culture medium; for example, using sakē lees as the culture medium for our meat alternative creates a light and mild-tasting product. This may be easier to use as processed meat. Another major strength is that almost any culture medium materials that are sources of nitrogen or carbon can be used, as long as they do not have an extremely high salt concentration or contain heavy metals.

“Is it edible?”

Thus, in the process of undertaking development work aimed at minimizing the cost of the culture medium and developing a fast-growing, highly nutritious meat alternative that we can bring to market as a product, we have discovered that the components of the culture medium affect the components of the fungus. The fact that differences emerge in the components of the koji mold cells according to the culture medium used resembles agriculture, where differences in the soil of agricultural land alter the sweetness and nutritional value of tomatoes. Similarly, we can produce changes in the flavor of our koji mold meat alternative by altering the way in which we cultivate it.

Diversity in the culture medium used in koji mold production leads directly to diversity in such aspects as the flavor and nutrients of the meat alternative. If the varieties of meat alternatives available increase to suit different uses, the possibilities offered by meat alternatives will likely grow further.

In 2006, the Brewing Society of Japan certified three varieties of koji mold as Japan’s “National Fungi,” in recognition of their status as precious assets that our forebears raised and skillfully utilized since time immemorial. In Japan, koji mold was identified from among the various fungi as something that could be eaten as a fermented food, and came to be used to produce miso, soy sauce, and sakē, among others. You might not have been aware of it, but the flavors of Japanese cuisine are all down to koji mold. I feel it would be no exaggeration to say that Japanese people’s food preferences have been shaped by koji mold.

The catalyst for us embarking on our quest to develop a meat alternative was a simple remark from a student, who was using koji mold in an experiment: “Is it edible?” I doubt that student would have said such a thing or readily put it in their mouth if it had been a fungus collected from soil.

As I recall, a fungus-based meat alternative has already reached the market overseas in the form of a meat alternative made from Fusarium. Fusarium is a filamentous fungus that inhabits soils worldwide and some of the fungi in this genus are known to be major plant pathogens in agriculture. One could say that this is the reason why research has progressed in this area, but it might also be the cause of reluctance to consume it, as this fungus is not already used in food production. One of the biggest hurdles that meat alternatives have to clear is a lack of prior experience of eating them, but koji mold does not suffer from this problem. If we can improve the flavor further, it will likely become a powerful new option as a source of protein.

In tasting sessions, we have received quite a few comments along the lines of “It’s very tasty. There would be no problem at all in making this a commercially available food product.” (Figure 3). Accordingly, we hope to spread the word about this new form of Japanese food culture, which leverages koji mold as Japan’s National Fungus.

Figure 3. A koji mold-based meat alternativeOur meat alternative, prepared by simply mixing it with salt, shaping it, and then frying it in oil. Boasting an appealing aroma, it is tasty enough to feature on ordinary menus without even needing to use the term “alternative.”