Sea temperatures are rising. Japanese coastal waters in particular have seen a rise of 1.28°C over the last 100 years, which is around double the increase of 0.61°C in the global average. The habitats of a variety of marine organisms have changed over this period, and the conventional ecosystem balance is breaking down. Climate change is thought to be a factor in this, but the precise reasons are still unclear at this stage. However, using environmental DNA microanalysis, it has become possible to gain an accurate understanding of current ecosystems without capturing living creatures. By learning what kinds of organisms inhabit Japanese coastal waters, we will be able to make the coastal fisheries industry more efficient.

Special Feature 1 – Climate Change and Japanese Food The changing ecology of coastal organisms: How will the coastal fisheries industry adapt?

composition by Yumi Ohuchi

illustration by Rokuhisa Chino

Global warming —— and even what has been termed “global boiling” —— is taking place right now, and rising sea temperatures are causing changes in the marine habitats of fish. Symbolic of this is the shocking report that southerly Fukuoka Prefecture has been overtaken by the northernmost prefecture Hokkaido as the area of Japan with the highest catch of pufferfish.

Fish, shellfish, crustaceans, seaweed, and other marine organisms all have particular temperature conditions that they favor, depending on their species, and they cannot regulate their temperature like humans. While fish are capable of swimming and can therefore move to waters of the right temperature, organisms that cannot move will weaken or become extinct because they are unable to tolerate these changes.

Fish catches in Japan have been falling

The crisis in Japan’s seas actually began before attention began to focus on the problem of climate change to the extent we see today. The biggest problem is overfishing, which has resulted in sharp declines and even extinction of certain fish species at a local level. For example, the specialty of Fukuoka Prefecture’s Hakata district is mentaiko, made from the roe-filled ovaries of the Alaska pollock (Theragra chalcogramma). Overfishing has caused the population of Alaska pollock in Japanese coastal waters to plummet, leaving the nation dependent on imports. In addition, along with water pollution, landfill and reclamation of coastal land arising from industrialization have caused a decline in coastal organisms. At the same time, while the discharge of household wastewater into the sea has been curtailed in order to improve water quality, another problem has arisen, because the consequent reduction of nutrients in the sea has made it difficult for the marine organisms that feed on them to grow.

Japan’s total fish catch has been in decline for quite some time, having peaked in 1984. Coupled with rising sea temperatures due to climate change, it would be fair to say that the situation facing our seas is becoming even more serious.

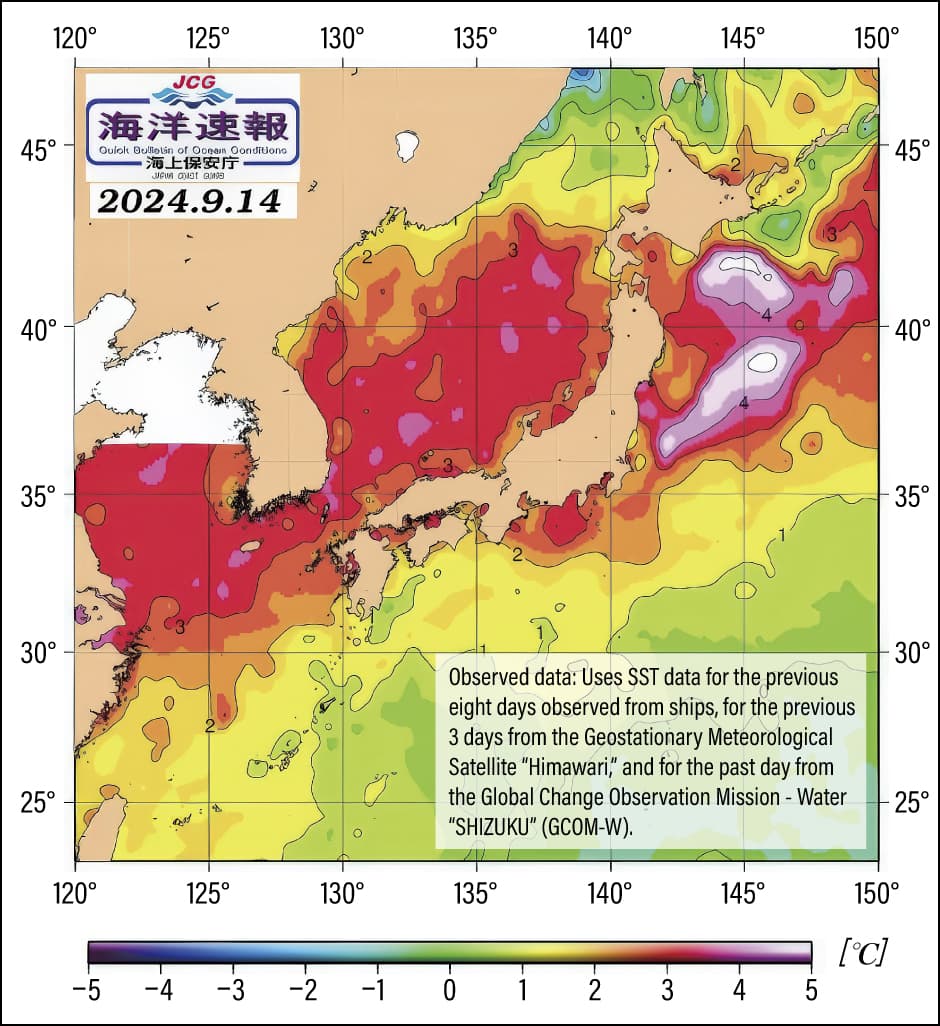

According to data from the Japan Meteorological Agency, the annual average sea surface temperature (SST) in coastal waters around Japan has risen by 1.28°C over the 100 years to 2023, which exceeds the corresponding figure for the global ocean (up 0.61°C/100 years). The extent of this change varies according to the region and time period, but if we look at the difference between the SST observed on September 14, 2024 and the 30-year average SST for the period 1991–2020, we can see that the temperature of Japanese coastal waters rose by at least 1°C across the board, with many areas seeing rises of 3°C or more (Figure 1).

Japan Coast Guard website. Last accessed: September 14, 2024.

Japan Coast Guard website. Last accessed: September 14, 2024.

Figure 1. Sea surface temperature anomaliesChart showing sea surface temperature anomalies on September 14, 2024, following a prolonged and severe heat wave (Japan Coast Guard). Almost all of Japan’s coastal waters show a rise in sea temperature above the 30-year average for 1991–2020.

In tropical and subtropical regions where sea temperatures have always been high, a further temperature rise will not lead to a serious deterioration of living conditions for the local fish. However, in places like Japan, where the sea temperature has not been all that high until now, rising temperatures will have a major impact.

As demonstrated by the fact that it is considered a local specialty of Shimonoseki City in Yamaguchi Prefecture, the aforementioned pufferfish was originally caught in abundance in western Japan, and was virtually unknown up in Hokkaido. However, as sea temperatures rose, they migrated northward, and Hokkaido’s pufferfish catch has increased in the region of sevenfold over the last decade (2013–2023). On the other hand, a problem has emerged in the form of a marked decline in catches of salmon, one of the island’s specialties. In particular, the catch of chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) saw a year-on-year decline of 36.4% (as of the end of September 2023). Other changes in the marine habitats of many other fish species have also been identified. For example, the mackerel (Scomber) and yellowtail (Seriola quinqueradiata) typically found in the southern island of Kyushu have migrated as far north as Aomori Prefecture and Hokkaido’s Shiretoko Peninsula, while Kyushu is seeing an increase in subtropical fish more usually caught even further south in Okinawa Prefecture, such as flying fish (Prognichthys agoo).

A complex chain of events alters the ecosystem balance

Many coastlines are experiencing progressive rocky shore denudation, a phenomenon in which seaweed beds decline, endangering not only the seaweed, but also the sea creatures that feed on it. The root causes of rocky shore denudation include water pollution and overconsumption by sea urchins and other marine creatures, but rising sea temperatures are also a factor, and it is thought that these factors form a complex chain of events that is altering the ecosystem balance.

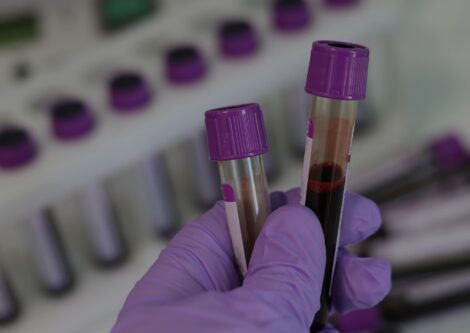

To combat these problems, we need to gather data to ascertain what fish inhabit Japanese waters and how their populations are changing. However, as fish swim freely through the seas, undertaking a comprehensive investigation of their species and population sizes is extremely tricky. As such, in a joint study with Tohoku University and other partners, we are adopting a new approach based on using environmental DNA to investigate fish species.

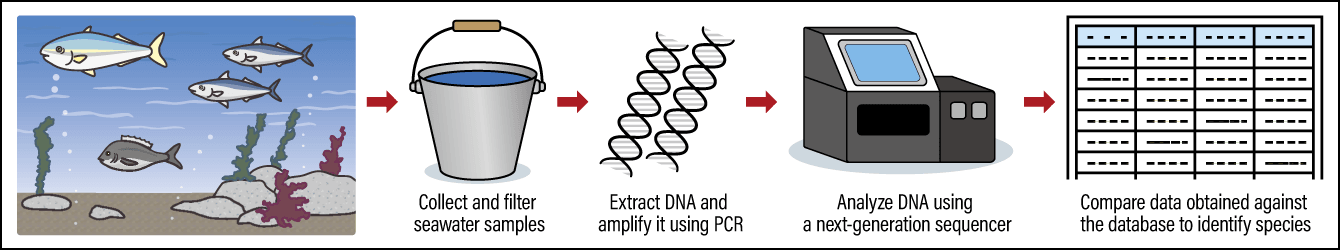

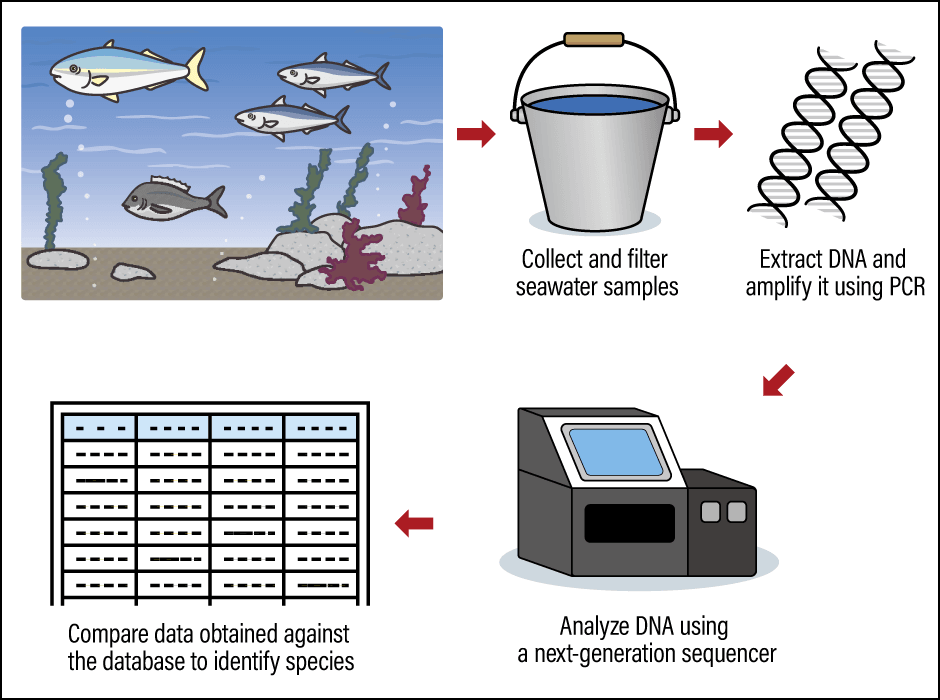

Environmental DNA is DNA of biological origin contained in such substances as fish feces and mucus that have dissolved into the sea or other environments. By extracting the minute traces of environmental DNA in seawater samples, amplifying it using a technique called polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and using next-generation sequencers to analyze it, we can learn about the fish that inhabit those waters (Figure 2). A larger quantity of DNA implies the presence of quite a few fish of that species. As the environmental DNA discharged by creatures remains in the environment for no longer than about a month, we can also identify changes through observations over time.

Compiled with reference to Fisheries Division of Forestry and Fisheries at Tsushima City Department of Agriculture,

Compiled with reference to Fisheries Division of Forestry and Fisheries at Tsushima City Department of Agriculture,Satoquo Seino, Tsushima Gyorui Zukan (Tsushima Fish Pictorial), pp. 56, 2019.

Figure 2. How environmental DNA surveys are conductedAfter collection, seawater samples are filtered, and the DNA is extracted. PCR is used to amplify the DNA before analysis using a next-generation sequencer. When collecting the seawater samples, great care must be taken to ensure the collectors’ DNA does not become attached to the collection equipment or contaminate the water.

Surveys are being conducted nationwide; since 2016, we have been collecting coastal seawater in Tsushima City, Nagasaki Prefecture, and undertaking ongoing monitoring of environmental DNA. We compiled our bulletins through to 2018 into a pamphlet entitled Tsushima Fish Pictorial, which is published on the Tsushima City government’s website. In response to the 2010 meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biodiversity, which was held in Aichi Prefecture, Tsushima City established a council to promote the creation of marine protected areas. Discussions by this body are led principally by promotion council members drawn from the fisheries sector. In partnership with Kyushu University, the promotion council carried out a fact-finding survey of the area and continues to undertake surveys and research.

Thanks to the Tsushima Current, which is an offshoot of the Kuroshio Current, Tsushima’s coastal waters are an abundant fishing ground. However, just like other fishing grounds, they face many problems, such as declining marine resources, as well as falling numbers of fishers and the increasing average age of those who remain. Catches of the fish renowned as specialties of Tsushima are on the decline, including premium fish varieties —— for example, horsehead tilefish (Branchiostegus japonicus), blackthroat seaperch (Doederleinia berycoides), and red seabream (Pagrus major). Among the root causes are problems such as overfishing, but rising sea temperatures are also believed to be a factor.

The diversity revealed by environmental DNA

At the same time, DNA from almost 90 fish species was detected in 10 L of seawater collected from Tsushima coast in our environmental DNA survey. This figure is one of the highest for the coast of the Japanese archipelago, and demonstrates the sheer diversity of fish species in Tsushima. However, as we use samples of seawater collected along the coast, the survey focuses on coastal fish, and we are unable to detect DNA from deep-sea fish such as Japanese tilefish and blackthroat seaperch.

Of the fish species detected, the most common was the grass puffer (Takifugu niphobles); unfortunately, this species is unsuitable for culinary use, due to its poison (Table). The top 30 includes fish typical of Tsushima, including largescale blackfish (Girella punctata) in third place, and sixth-placed flathead gray mullet (Mugil cephalus), which are found in profusion in inlets. In 25th place is red naped wrasse (Pseudolabrus eoethinus), which is a familiar inshore fish, while in 28th and 29th place respectively are false kelpfish (Sebastiscus marmoratus) and kelp grouper (Epinephelus moara), both of which are traded for high prices. Hatchery supplementation of kelp grouper is being carried out in Tsushima to maintain and increase stocks. Ninth-placed Japanese horse mackerel (Trachurus japonicus) is a very familiar fish throughout Japan, but catches have been falling in recent years.

| Rank | Family | Common Japanese Name (English Name) | Scientific Name |

| 1 | Tetraodontidae | Kusafugu (Grass puffer) | Takifugu niphobles |

| 2 | Clupeidae | Kibinago (Silver-stripe round herring) | Spratelloides gracilis |

| 3 | Girellidae | Mejina (Largescale blackfish) | Girella punctata |

| 4 | Atherinidae | Gin-iso-iwashi (Cobaltcap silverside) | Hypoatherina tsurugae |

| 5 | Girellidae | Kuromejina (Smallscale blackfish) | Girella leonina |

| 6 | Mugilidae | Bora (Flathead gray mullet) | Mugil cephalus |

| 7 | Blenniidae | Hoshi-ginpo (Stellar rockskipper) | Entomacrodus stellifer stellifer |

| 8 | Siganidae | Aigo species | Siganus sp. |

| 9 | Carangidae | Maaji (Japanese horse mackerel) | Trachurus japonicus |

| 10 | Blenniidae | Rōsoku-ginpo (Barred-chin blenny) | Rhabdoblennius nitidus |

| 11 | Labridae | Kaminari-bera (Cutribbon wrasse) | Stethojulis interrupta terina |

| 12 | Stichaeidae | Dainan-ginpo (Prickleback) | Dictyosoma burgeri |

| 13 | Labridae | Hoshi-sasanoha-bera (Bambooleaf wrasse) | Pseudolabrus sieboldi |

| 14 | Apogonidae | Kurohoshi-ishimochi (Spotnape cardinalfish) | Ostorhinchus notatus |

| 15 | Tetraodontidae | Torafugu species | Takifugu sp. |

| 16 | Scombridae | Saba species | Scomber sp. |

| 17 | Clupeidae | Konoshiro (Dotted gizzard shad) | Konosirus punctatus |

| 18 | Labridae | Honbera (Chinese wrasse) | Halichoeres tenuispinis |

| 19 | Atherinidae | Mugi-iwashi (Bearded silverside) | Atherion elymus |

| 20 | Blenniidae | Kaeru-uo (Mottled blenny) | Istiblennius enosimae |

| 21 | Engraulidae | Katakuchi-iwashi (Japanese anchovy) | Engraulis japonicus |

| 22 | Scaridae | Aobudai (Knobsnout parrotfish) | Scarus ovifrons |

| 23 | Tripterygiidae | Hebi-ginpo (Snake triplefin) | Enneapterygius etheostomus |

| 24 | Pempheridae | Minami-hatanpo (Silver sweeper) | Pempheris schwenkii |

| 25 | Labridae | Aka-sasanoha-bera (Red naped wrasse) | Pseudolabrus eoethinus |

| 26 | Oplegnathidae | Ishidai (Barred knifejaw) | Oplegnathus fasciatus |

| 27 | Plotosidae | Gonzui (Eeltail catfish) | Plotosus japonicus |

| 28 | Scorpaenidae | Kasago (False kelpfish) | Sebastiscus marmoratus |

| 29 | Serranidae | Kue (Kelp grouper) | Epinephelus moara |

| 30 | Gobiidae | Kuro-yoshinobori (Amur goby) | Rhinogobius brunneus |

Satoquo Seino, Tsushima Gyorui Zukan (Tsushima Fish Pictorial), pp. 58-59, 2019.

On the other hand, many fish that are not customarily eaten locally have also been detected. However, these do include fish that are popular in other regions. For example, silver-stripe round herring (Spratelloides gracilis; second place), cobaltcap silverside (Hypoatherina tsurugae; fourth place), and dotted gizzard shad (Konosirus punctatus; 17th place) are, respectively, firmly embedded in the culinary culture of Okinawan cuisine, southern Shikoku’s Tosa cuisine, and Tokyo’s Edo-style sushi. In 23rd place is snake triplefin (Enneapterygius etheostomus). While this fish tends to be disregarded locally, and referred to by a mimetic name that could be translated as “that wriggly thing,” it is prized in Tokyo as a premium fish best enjoyed in tempura, and its name is written in characters that translate as “silver treasure.”

Thus, fish-based culinary cultures with distinctive features that differ from one region to another have developed in Japan, displaying a diversity of a kind that is rare even on a global scale. I think this provides us with a lead for solving problems involving the sea. While cutting CO2 and other such environmental measures are, of course, important, it is difficult to achieve effects within a short period. As such, another key measure is to adapt to changes in nature and protect fish species in decline while creating new forms of culinary culture centered on the fish species that can be caught.

For example, as there is no culture of eating pufferfish in Hokkaido, they are shipped to Yamaguchi Prefecture and other places where demand is high. Although this is one approach, the administrative effort and cost involved in their transportation is not insignificant, so we are also starting to see moves to consume pufferfish locally.

In order to incorporate such fish as new forms of culinary culture, it is crucial to learn from regions where they are well-established in the culinary culture about such matters as their appropriate handling and the tastiest ways to cook them. I myself have tried deep-frying cobaltcap silverside suage-style (without breading or batter), based on a recipe I received from a friend in Kochi, Shikoku, and was impressed to discover that it was very tasty, despite not being exploited for widespread commercial purposes. In Kochi, there is also a culture of eating this fish raw, as sashimi, but deep-frying suage-style is a simple cooking method that has the advantage of boosting one’s calcium intake, as even the bones can be eaten (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cobaltcap silverside deep-fried suage-styleCobaltcap silverside is a small fish. Its presence in open sea locations off Tsushima and other parts of the Kyushu coast has been confirmed using environmental DNA. While it is a familiar part of Kochi people’s diet, it is not widely used for culinary purposes in other regions.

In addition to incorporating different forms of culinary culture in this way, I believe it is also important to reconsider existing local cuisine. In Tsushima, there is a local dish called kusabi miso, made by baking red naped wrasse (or any other wrasse variety) with the skin and scales still attached, and then mincing the flesh up and mixing it with miso (Figure 4). Apparently, the key tip is to bake the fish in the frying pan without removing the skin, as this effectively steams the flesh, while sealing in the umami and aroma.

(Photographs courtesy of Tsushima City / Wrasse photograph by Takuya Morihisa)

(Photographs courtesy of Tsushima City / Wrasse photograph by Takuya Morihisa)

Figure 4. Kusabi misoThis local dish from Tsushima also holds significance as a preserved food. The fish in the photograph is red naped wrasse. This is one of the subtropical fish species that are found in increasing numbers off the Tsushima coast.

A next-generation fisheries industry that taps into scientific verification

While it might be difficult to create a large market through such efforts to shape or tap into culinary culture, I believe initiatives of this kind will assist in developing tourism resources and building a circular society based on local production for local consumption. Given the factor of rising sea temperatures, another approach would be to make use of the aforementioned wrasse, flying fish, kelp grouper, and flathead gray mullet, as well as the dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus) and other fish that are migrating from the tropics to warm seas in the temperate zone. Unfamiliar in Japan, the dolphinfish is popular overseas, where it is regarded as a premium fish; in Hawaii, it is called mahi-mahi. It has for some time been caught in abundance in Miyazaki Prefecture, but catches have also been growing further north in Fukui Prefecture, and, due also in part to the weak yen, dolphinfish exports are increasing.

At Kyushu University, we have set up a marine education project called Kyushu University Umi Tsunagi, and are currently undertaking activities relating to conservation of the marine environment. Our first focus is to spread the word and make this issue a topic of conversation throughout the town via this project, as well as the radio and other media, and assorted events, and also to undertake activities that inform people about the diversity of fish-based culinary culture.

While this kind of approach targeting ordinary consumers is important, it is those working in the fisheries industry who sustain the supply of fish in Japan. Although the industry faces a tough situation, with the population of workers in the sector falling as a consequence of the decline in fish catches described above, I believe there is also a need for fishers themselves to conduct surveys of marine creatures inhabiting their local waters and build up a stock of data, so that they can accurately ascertain the current situation. In addition, they should publish this data externally and, based on evaluations and discussions, think creatively about the fisheries industry of the future. Our role as researchers is, I believe, to work closely with fishers to support them in this process.

Accordingly, I have recently been focusing my attention on the power of the next generation. In Tsushima City, local elementary school students are participating in a special “children’s sector” of the meetings with fishers that the city government organizes. Children’s participation has revitalized the meetings in various ways; for example, in response to the opinions expressed by fishers, who have a tendency to be apathetic, due to a lack of younger workers to succeed them, the children offer harsh, but accurate views, with comments such as, “You say it’s no good, but have you actually collected proper data?” As it is these children who are going to be growing up in this region in the years to come, they take the issue even more seriously than the adults. Watching these children, I get the feeling that, rather than adults teaching them, there are many things they can learn by engaging in activities alongside us.

Right now, marine production and consumption in Japan face a major turning point. However, climate change has occurred since ancient times, and humans have overcome a variety of difficulties by means of adaptation. I believe it is vital for us to foster the cultural power required to address the problems faced by the sea, while tapping into the wisdom of our ancestors, the power of the next generation, and scientific evidence.