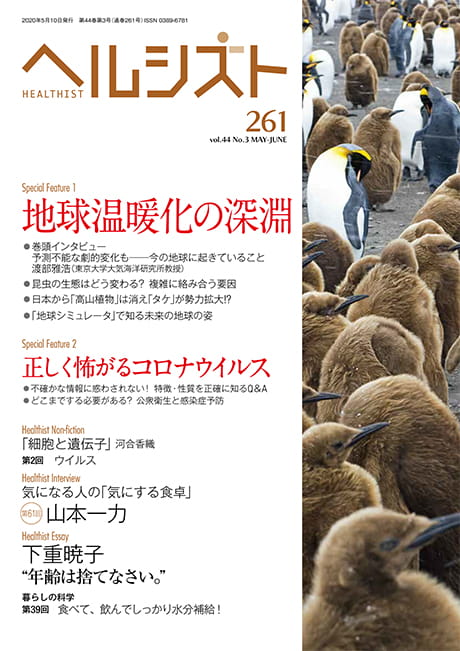

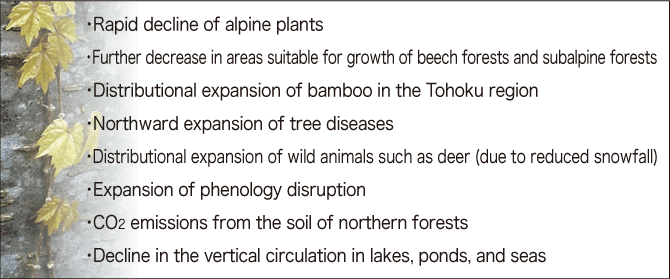

If the air temperature rises due to climate change, the environment suitable for plants will shift northward. In that process, the most affected plants will be alpine plants that grow on high mountains in a low-temperature environment. If the air temperature continues to rise, alpine plants may eventually lose their habitat and almost disappear from Japan. There is also a prediction that the areas suitable for beech forest in Shirakami-Sanchi, a UNESCO World Heritage site, will decrease to around 20%. On the other hand, bamboo, which favors warm climate, seems to be expanding its power northward.

Special Feature 1 – The Abyss of Global Warming Will “alpine plants” disappear from Japan and “bamboo” expand power!?

composition by Takakazu Kawasaki

Organisms including trees and forests are highly susceptible to the impacts of global warming. Although the term is “warming,” it involves not only changes in temperature but also changes in various climatic conditions such as rainfall and snowfall patterns, so it may be more appropriately referred to as climate change (or climate variations). Around the globe, there are many cases where a decrease in the amount of rainfall causes forests to lose sustainability and leads to expansion of grasslands, or deserts in the worst case. In California, the United States, for example, forests exist, but due to the dry climate which causes frequent wildfires, the vegetation is sometimes dominated by shrubs.

In contrast, Japan’s annual rainfall ranges between 1,000 and 4,000 mm. As there is at least about 1,000 mm annual rainfall, enough for forest vegetation. Most parts of Japan naturally become forests without requiring human intervention, so the effects of climate change on ecosystems in Japan tend to be regarded only for temperature. However, caution is required because while some trees favor rainy, humid climates, other trees favor relatively dry climates.

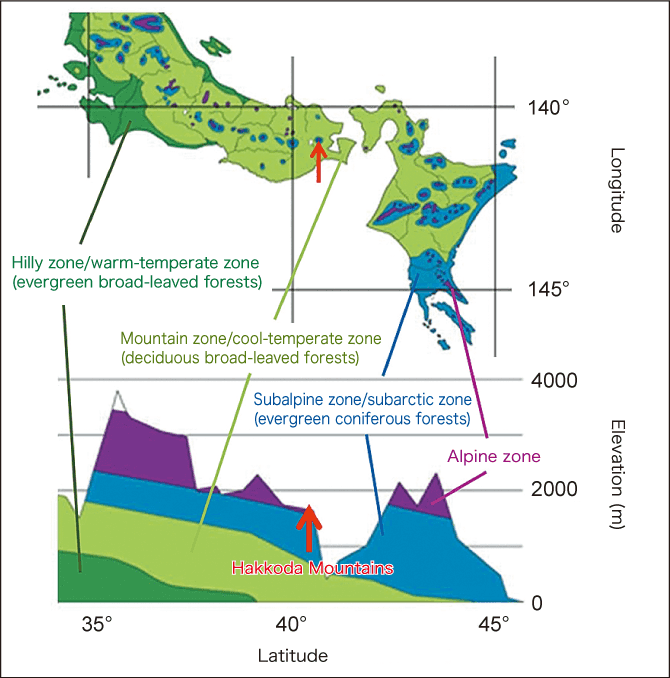

Figure 1. Forest zones in JapanThere is a risk that the elevations of the subalpine and subarctic zones will rise due to warming and the alpine zone will be lost. (Source: Data provided by the Biodiversity Center of Japan, Ministry of the Environment, partially modified)

Most threatened plants are alpine plants

Taking an overview of Japan’s forest vegetation, in southernmost Okinawa, there are evergreen broad-leaved forests of the warm-temperate and subtropical zones. Toward the north (or higher in elevation), there are deciduous broad-leaved forests, and further north (or higher in elevation), evergreen coniferous forests of the subarctic zone (or subalpine zone). In Hokkaido, there are subarctic coniferous forests in the plains, and the alpine zone near mountain summits.

When warming occurs, the climate suitable for growth of the respective plants and trees shift northward, so the vegetation gradually moves toward the north as well. Then, the most threatened vegetation would be plants of the alpine zone, which locate mostly at the summit of mountains.

At the mountain with low summit elevation, the temperature environment suitable for plant growth will shift higher and higher in elevation due to warming, and eventually plants will not be able to grow even at the summit.

For example, the alpine zone of Mt. Fuji (elevation: 3,776 m) is above 2,600-2,700 m, and there is only about 1,000 m to the summit. The alpine zone of Japan’s second highest peak, Mt. Kitadake (elevation: 3,193 m), only has an altitudinal range of 500-600 m. The temperature drops by 0.6°C for every 100 m of elevation. Meanwhile, if humans continue their current activities without reducing emissions of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), it is said that the temperature will rise by 4-5°C by the end of the 21st century. Thus, according to calculation, if the temperature rises by 5°C, there will no longer be alpine zone plants on Japanese mountains with an elevation of up to 2,900 m.

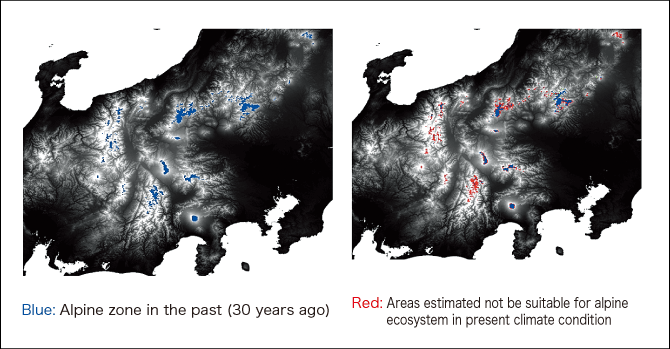

Figure 2. Present alpine zone predicted based on distribution conditions of the past (30 years ago)Areas of the alpine zone in the ChŪbu region that are estimated to have been lost over the past 30 years (red part).

(Source: Iwai, et al., unpublished data)

The alpine zone in Japan is located at the lowest elevation among the alpine zones in the world because the heavy snowfall in winter and strong wind make it difficult for trees to grow. However, snowfall is decreasing as we experienced an extremely small amount of snowfall in 2019 due to a warm winter. Therefore, it is said that a substantial proportion of the alpine zone will disappear even if humans can reduce CO2 emissions and achieve the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP2.6), which is a low-emissions scenario to limit the temperature increase by the end of the 21st century to 2°C.

Plants are not the only organisms affected by warming.

For example, the number of rock ptarmigans (Lagopus muta) living in the alpine zone has been gradually decreasing. More than the effects of the temperature change caused by the warming, the number has been affected by the fact that animals such as foxes, monkeys, and deer, which had been living at low elevations, have come up to the habitat range of the rock ptarmigan and eaten rock ptarmigans’ eggs and chicks. The effects of warming are already observed in animals before the shifting of vegetation.

In this manner, the projected change in terrestrial ecosystems is that, if climate change occurs, fast-moving animals will shift to higher elevations at a fast pace, and plants and animals which could only live at high elevations will have no place to go and be driven out.

The excessively expanded distribution of bamboo is causing harm

With regard to forests, it is already known that coniferous forests of the subalpine zone have been declining due to changes in rainfall patterns and temperature. While subalpine coniferous forests are roughly at an elevation of 1,500-2,500 m, many reports indicate that subalpine coniferous forests, including those in the Hokkaido lowlands, are declining at around their lower or southern limits of distribution.

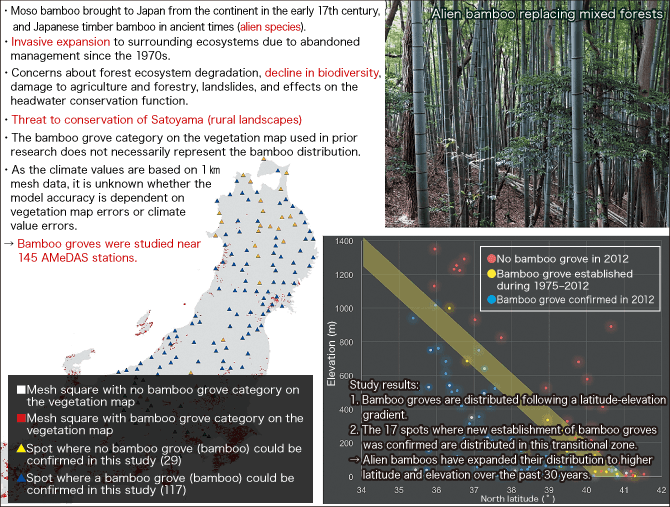

Bamboo species originally grew mainly in the tropical and subtropical zones. According to our study, bamboos are expanding northward. The two major bamboo species are the Japanese timber bamboo (Phyllostachys bambusoides) and the moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis), both of which were introduced to Japan from the Chinese continent. The Japanese timber bamboo was brought to Japan in ancient times (some say it has a Japanese origin) and the moso bamboo in the Edo Period [early 17th to late 19th century] (some say it was introduced in the Nara Period [8th century] or the Kamakura Period [late 12th to early 14th century]). Both bamboo species had been heavily used in Japan as a food, fuel, bamboo-ware materials, and materials for agriculture and architecture. Today, however, bamboo use declined, and the excessively expanded distribution of bamboo, particularly in western Japan, is causing troubles.

A tree only grows about 1 m at the most in a year, but a bamboo stalk grows to around 10 m in a year. If a certain forest area is felled, and there is a bamboo grove nearby, the bamboo extends rhizomes and develops bamboo shoots. When the bamboo shoots grow to about 10 m high in a few weeks, they cast shadows over the young trees, and inhibit the growth of the trees.

The temperature on the northern part of the Kitakami Mountains (Iwate Prefecture-Miyagi Prefecture) used to be around the lower limit for growth of bamboo. However, as the average temperature rose by 0.5°C over the past 30 years, bamboo started to grow there. If the present trend continues, bamboo will start growing in Hokkaido by the end of the 21st century.

Bamboo is said to spread its roots and reinforce the soil. However, the roots are actually shallow, so bamboo groves on slopes have seen damage where the slope suddenly slides down along with the rooted soil layer after heavy rain.

Bamboo is usually spread by humans. In order to reduce such damage caused by bamboo invasion, we need to be careful not to plant bamboo in new places without sufficient thought, and if we do plant bamboo, to make sure it is managed continuously.

Figure 3. Distributional expansion of alien bamboo forestsOver the past 30 years, the average air temperature has risen by 0.5°C, and bamboo has expanded northward in Aomori Prefecture. (Source: Takano et al. (2018), partially modified)

Relatively many beech forests remain on the Sea of Japan side of the country. Among deciduous broad-leaved forests, beech forests tend to be distributed in rainy or snowy areas. However, the climate is now changing to have a higher temperature and less snow. Therefore, some predict that, if the temperature rises by 2.5-4.0°C in the future, the area with suitable environment for beech forest in Shirakami-Sanchi, a UNESCO World Heritage site, will decline to about 20% of the present area.

Even if the beech disappeared, the forest can be maintained as long as other tree species could replace it. Specifically, species such as deciduous oaks, hornbeams, chestnut, and evergreen oaks can grow under the predicted climate, so such trees are likely to substitute the beech. However, when a large beech tree dies, will a new deciduous oak, hornbeam, or chestnut smoothly take over its place and grow? Probably not. The deciduous oak is an acorn tree, and if acorn seeds are to be carried, possibly by mice. Nevertheless, the home range of mice is small, so they do not necessary carry acorns to desirable places.

The situation becomes more difficult if dwarf bamboo dominates the forest floor. If a beech canopy tree dies, the spot becomes bright with sunlight. Then, the dwarf bamboo grows at once and turns the place into a dwarf bamboo bush where it becomes too dark for acorns to grow.

This is said to have actually happed on Mt. Tsukuba (elevation: 877 m) in Ibaraki Prefecture. The parts of the forest where the beech trees died have now turned into dwarf bamboo bushes.

Due to warming and a decrease in rainfall, the beech forest at the summit of Mt. Tsukuba has declined and turned into a bamboo grass field. (Source: Project Team for Comprehensive Projection of Climate Change Impacts, 2008)

Expansion of forest disease and pests

If the warming progresses, expansion of some disease and pests cause a decline of forests and trees.

The red-necked longhorn (Aromia bungii), an insect species which used to live in mainland China and Taiwan, parasitizes cherry, plum, and peach trees, and makes the trees wither by eating the inside of the trees. However, the relationship between the red-necked longhorn and warming is not clear.

Meanwhile, the warming is feared to have impacts on the pine wilt and Japanese oak wilt diseases.

In the case of pine wilt, a longhorned beetle called the Japanese pine sawyer (Monochamus alternatus) carries pine wood nematodes (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus), small worms which cause the disease, that enter its body.

In the case of Japanese oak wilt, the oak ambrosia beetle (Platypus quercivorus) enters inside oak with the fungus that causes the withering (Raffaelea quercivola) attached to its body, and lays eggs, while causing the oak to be infected with the fungus at the same time. The larva of the oak ambrosia beetle grows by eating the oak tree decomposed by the causal fungus.

Japanese oak wilt occurs when an oak ambrosia beetle enters inside oak with the causal fungus attached to its body, and lays eggs, causing the oak to be infected with the fungus at the same time. (Photograph courtesy of Tohru Nakashizuka)

The habitat ranges of both the Japanese pine sawyer and the oak ambrosia beetle are decided by temperature, and their northern limits had been the border between Aomori and Iwate Prefectures. However, their habitat ranges are expanding into Aomori Prefecture due to warming, and could further expand to Hokkaido in the future.

In contrast to forests and plants on land, the marine organism that is currently feared to be most affected by warming is coral.

While coral reefs have algae inhabiting their skeletons, when the water temperature rises due to warming, the algae escape from the coral and cause coral bleaching. Coral bleaching is expanding at a tremendous pace in coastal areas near Japan, bleaching is frequently observed in the Sekisei Lagoon (waters between Ishigaki Island and Iriomote Island), which is famous for coral. It is said that the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), which devours coral, is also increasing in number due to warming.

Another concern is acidification of sea water caused by increasing concentration of CO2. The ocean water absorbs an enormous amount of CO2, but when CO2 dissolves in seawater, the seawater becomes carbonated. As a result, shellfish and coral that are made of calcareous matter will not be able to survive.

Coral reefs are cradles of the ocean with extremely rich biodiversity. If coral becomes unable to survive due to a rise in the seawater temperature and acidification, some fishes will no longer be able to spawn in those waters, and fishery resources will become depleted. Such waters will also lose their current economic value as tourism resources.

Figure 4. Projected effects on mountains in JapanProjected effects of warming on mountains in Japan include a decline in alpine plants, a decrease in areas suitable for subalpine plants, and northward expansion of bamboo.

The air temperature in Siberia will rise by 8°C

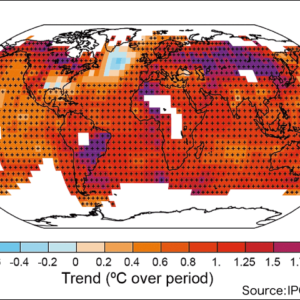

Many people may think that warming will cause a temperature rise also in tropical and subtropical zones, but the temperature rise there will not be as large as in the north. Also, the temperature rise in the southern hemisphere will not be so significant either, as the ocean makes up a large proportion. In areas such as Thailand and Australia, however, there will be a risk that aridity will intensify in the season and cause wildfires.

The areas that will experience the sharpest temperature rise due to warming are the Arctic and Siberia. In particular, the temperature in Siberia is assumed to rise by about 8°C by the end of the 21st century.

On the other hand, some people think that the melting of ice in the Arctic Ocean and frozen soil in Siberian forests called taiga (boreal forests) is not all bad. They believe it would be advantageous if ice in the Arctic Ocean melts, and sea routes connecting Asia and Europe could be developed, or if the currently frozen land area could be used for agriculture.

However, if the frozen soil in taiga melts, methane gas will be released from underground. Methane gas is also emitted from tropical peat swamps. Methane gas, which has a 25-times larger greenhouse effect than CO2, has the risk of further accelerating warming.

It is not easy to prevent global warming. Even so, the most important step would be for us to reduce CO2 emissions as mitigation of global climate change. With regard to climate change, the most desirable approach for organisms is to conserve the ecosystem in its natural state. However, the ultimate means would be to conserve the species endangered by warming by way of keeping and propagating them in botanical gardens, aquariums, or zoos. For plants, botanical gardens throughout Japan have already formed a network and have embarked on an action to protect endangered species and alpine plants by recording their habitat areas.