When disaster strikes, what kind of meals are available at Japanese evacuation shelters? In the vast majority of cases, they consist of rice balls, snack breads, and bento boxes. It is not hard to imagine that consuming a menu like this for a month or more would be harmful to one’s health. In tough situations, diet inevitably becomes a secondary consideration. However, diet is too important to allow any time to be lost in tackling this issue. A radical rethink of food in such situations is required to prepare for the disasters likely to strike in the future.

Special Feature 1 – Nutritional Science for a New Age The dietary situation at evacuation shelters reflects modern nutrition problems

composition by Rie Iizuka

When the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, I visited evacuation shelters in my capacity as a dietitian. The dietary situation was generally poor and the physical condition of the evacuees deteriorated by the day. I witnessed for myself that, just like various other things, the situation in regard to meals at disaster sites was far grimmer than I could have imagined.

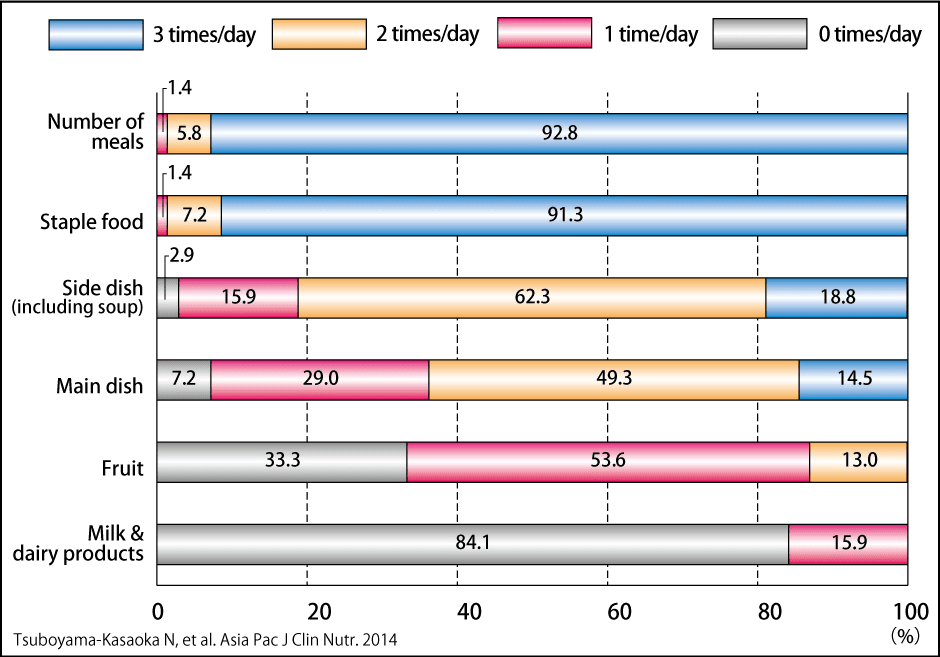

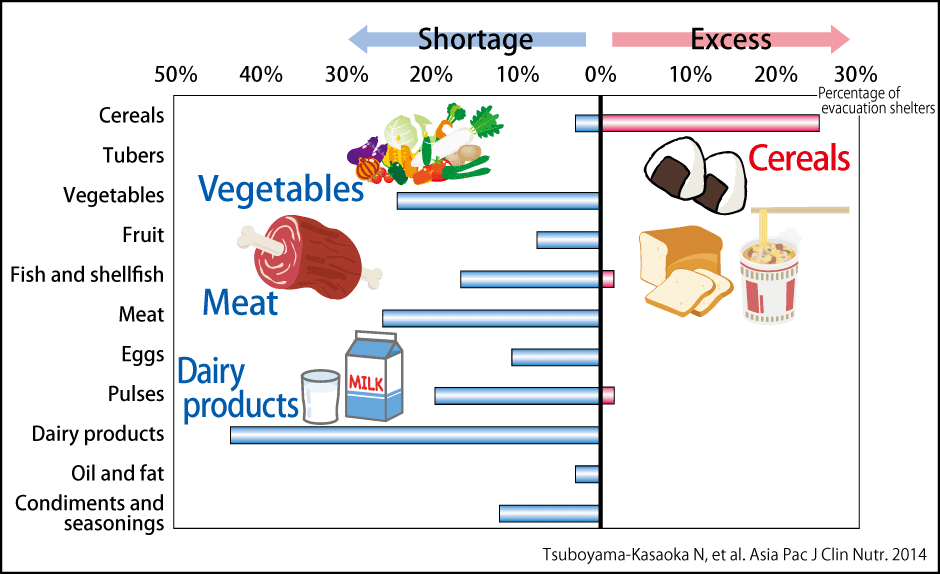

In the case of the Great East Japan Earthquake, the first issue was insufficient food at most evacuation shelters. I went to the city of Kesennuma in Miyagi Prefecture. Many of the 69 evacuation shelters there were providing no food or water whatsoever even a week after the disaster and one was still providing only one meal per day even after three weeks had passed (Figure 1). Something close to malnutrition was happening before my very eyes. Responding to a questionnaire 18 months after the disaster, evacuees overwhelmingly cited food as the thing that they had most wanted in the aftermath of the disaster.

Figure 1. Dietary situation at evacuation shelters following the Great East Japan Earthquake (early April)Survey conducted in early April 2011 at all 69 evacuation shelters in Kesennuma City. One evacuation shelter served a meal only once a day even after three weeks had passed. Another important point is the disparities between evacuation shelters, with some providing two meals per day. Almost all of the meals provided consisted of a staple food, with 7.2% of evacuation shelters not providing a source of protein such as meat or fish even once a day. If the evacuation shelters providing protein only once per day are included as well, more than 30% of meals at evacuation shelters were like this. In the vast majority of cases, fruit was served once or not at all, while 84.1% of shelters served no milk or dairy products whatsoever.

In addition, there was an imbalance in the food provided to them. Snack breads are often sent to disaster-stricken areas because of their long shelf lives. I have been informed that people who had to evacuate because of the West Japan floods in 2018 received a type of sweet bun called meron pan for breakfast every day for three months. Similarly, following Typhoon Hagibis in 2019, Danish pastries were supplied for breakfast at evacuation shelters every day for almost a month. The current reality is that the food provided is completely inadequate in terms of both calorie content and nutrients.

An overwhelming lack of protein and vitamins

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare subsequently drew up nutritional standards in the event of disaster, based partly on our data (Figure 2). Energy (calories) and protein are essential in order to maintain life. Moreover, as water-soluble vitamins are not stored in the body, people soon develop deficiencies if they do not consume them. In particular, B vitamins serve as coenzymes when carbohydrates are broken down by the body into energy and are therefore absolutely essential to the carbohydrate-heavy diet at evacuation shelters. Moreover, fresh fruit is hard to come by in disaster-stricken areas, but the vitamin C that it contains is also vital, as it increases stress tolerance.

Figure 2. Survey of meals provided at evacuation shelters following the Great East Japan Earthquake (for about a month after the disaster)As with Figure 1, the survey was conducted at all evacuation shelters in Kesennuma City. Evacuees were continually served meals that were overly carbohydrate-heavy, with a lack of dairy products, meat, and vegetables. Whereas people require 1,800 to 2,200 kcal of energy per day, only 29% of evacuation shelters met this requirement. Their diet was also lacking in protein and vitamins B1, B2, and C.

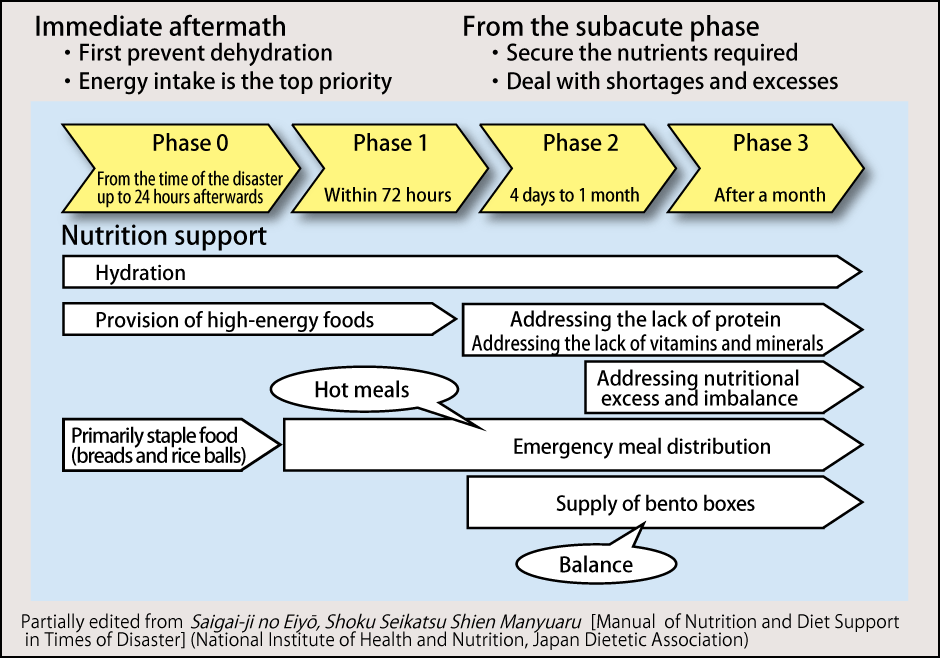

Since the Great East Japan Earthquake, government stockpiles have been built up and various guidelines on meal provision have been revised, partly with reference to our study (Figure 3). Even if people have to make do with bread or rice balls to start with, emergency meal distribution should be set up soon as possible, including a hot side dish or two. If bento boxes are provided, the number of side dishes increases, so the guidelines recommend that efforts are made to ensure a good nutritional balance.

Figure 3. Nutrition support process in the event of disasterEmergency meal distribution ensures hot meals are provided and, depending on how it is carried out, can enable any nutritional deficiencies in the bento boxes to be supplemented. It is necessary to enhance the nutritional side, putting in place the requisite conditions in the form of a supply of ingredients, kitchen utensils, and cooks, and to start with something simple, such as plain udon and ramen noodles without toppings.

While the meals supplied in the context of emergency meal distribution are hot, they are not always hearty dishes containing a lot of ingredients, such as tonjiru, vegetable-packed pork soup. Businesses have been able to respond more quickly in recent years, with some evacuation shelters starting to distribute bento boxes the day after evacuation in the wake of the West Japan floods in 2018.

However, a recent study we conducted showed that, while bento boxes provide an ample supply of energy and protein, they do not even come close to meeting people’s requirements for vitamins B1 and C. We ourselves had regarded the supply of bento boxes as a kind of goal, but the pitfall turned out to be that virtually all those bento boxes were based on deep-fried foods. At one evacuation shelter set up after Typhoon Hagibis struck East Japan in 2019, the menu on successive days went as follows: fried chicken bento, fried chicken bento, fried chicken bento, croquette bento, fried shrimp bento, and, at long last, Chinese steamed dumpling bento. As you can imagine, this kind of menu is lacking in vitamins. After that, we informed the authorities that we would like them to supplement the evacuees’ diets with items such as vegetable juice and milk that can be stored at room temperature.

Some people who have not experienced a disaster might think, “It’s only to be expected that nothing but rice balls and snack breads are available in an emergency” or “It’s only a temporary situation, so what’s the problem if the nutritional balance is out a bit for a while?” Even many of the evacuees in the shelters endure their dissatisfaction with their diet uncomplainingly.

However, if a diet of snack breads, rice balls, and bento boxes full of fried food continues for two or three months, it will not only fail to meet people’s basic nutritional needs, but also have longer-term effects on their subsequent health.

For example, there are people who have experienced the onset of lifestyle-related diseases triggered by meals high in sugar and fat that they received at evacuation shelters. A little while after a disaster, people begin to send confectionery to the evacuees as a form of support, so each evacuation shelter ends up with piles of sweets. The evacuees are free to eat them as they choose and children get into the habit of treating them as a kind of all-you-can-eat confectionery buffet. They fail to get out of this habit even after moving into temporary housing, resulting in some children becoming obese or developing tooth decay.

The meals in evacuation shelters affected not only people’s physical condition, but also their mental state. A little while ago, I had the chance to listen to a teacher from a disaster-afflicted school talking about their experience and discovered that some of their students had developed an aversion to curry with rice (usually a popular dish with children ) after the disaster. It seems that the evacuation shelters where they had stayed had served nothing but curry and rice, so the children had come to associate this monotonous diet with their traumatic experiences of the disaster. I have heard several similar stories. I cannot help but wonder what the outcome would be if a more enjoyable diet was provided at evacuation shelters.

What is really lacking is awareness of diet

I nearly wept at one evacuation shelter I visited after the Great East Japan Earthquake, when I watched a weary-looking elderly man take a bento box, sit down on the floor, and start to eat alone, looking down at the ground. In that moment, I strongly felt that one could not call that a meal.

If you are in a situation without adequate water and your meals for 10 days are nothing but dried-up snack breads, cold rice balls, and oily bento boxes, it becomes a feat of endurance. Meals that you have to endure are neither enjoyable nor tasty. Eventually, some people lose their appetite and stop eating. Coupled with the existing lack of nutrients, it becomes a very serious vicious circle.

Even where meals provide the necessary nutrients, a varied menu makes eating more enjoyable, as does enjoying conversation as one eats around a table with others. These are not merely optional extras in a diet, but rather essential elements for life. They are not aspects that should be neglected just because people are in evacuation shelters.

Why do meals at evacuation shelters end up being like this? What I feel right now is that people lack awareness or imagination even when it comes to ordinary meals, let alone the need to enhance support mechanisms and systems.

I recently discovered that the meals at the accommodation facilities where high-risk people were isolating to prevent the spread of COVID-19 were no different from those provided at evacuation shelters. And I had the feeling that I might have spotted the answer.

More specifically, one can understand to some extent that it is hard to provide high-quality meals at evacuation shelters when lifeline utilities have been cut off and ingredients cannot be procured. However, in the case of these accommodation facilities in city centers, food could easily be procured and prepared. And yet even under these conditions, people were being served rice balls or snack breads for breakfast and bento boxes full of fried food for dinner. Even if someone has no symptoms at present, they might go on to develop them and they therefore need to prepare their body by properly nourishing it. This applies even more so to those who already have a mild case of the disease. I am sure the menu would have been different if those providing the meals could have put themselves in the position of those eating them to a greater extent, realizing that people are likely to get fed up of having nothing but snack breads or that they will not get enough vegetables if they are served grilled meat bento boxes day after day.

I have been conducting research into disasters and nutrition for 10 years now. There is little research on this theme across the globe and when I first embarked on my work, there were only two articles that I could reference, including both publications in Japanese and in English. But, seeing the situation after the Great East Japan Earthquake, I was convinced that there was a need for this work and have been highlighting the need to add the term “disaster nutrition” to our vocabulary ever since. However, 10 years later, it has become clear that disaster and nutrition is not a discrete theme, but rather part and parcel of our everyday food problems. If the food situation is poor, people suffer a marked decline in their physical condition, coupled with the problem of lifestyle-related diseases. Lurking behind the provision of a repetitive menu is, I believe, the problem of a low consciousness of nutrition even here in Japan, where we usually have abundant options and can eat a varied diet as a matter of course.

Evacuation shelters in some places even serve wine

Finally, I want to talk about what I saw when I visited evacuation shelters in the Italian cities of Modena and Bergamo.

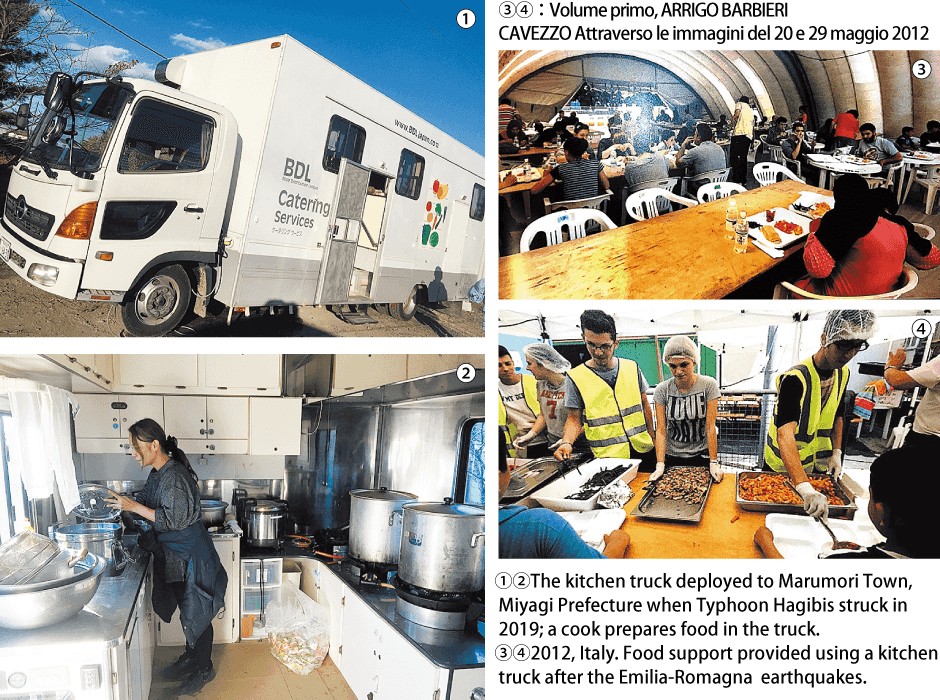

Italian evacuation shelters generally hold 250 to 300 people. In addition to containers serving as offices for the groups running the shelters, they have individual tents that are occupied by one to two families and are equipped with beds so that people do not have to sleep all huddled together on the ground. The shelters are also equipped with containers fitted out with toilets and showers, and also a kitchen truck, ensuring a certain standard of living from an early stage. Hot pasta dishes are served from the day of arrival and some evacuation shelters even serve wine. The shelters have a dining hall, enabling everyone to eat together—evacuees, volunteers, and government staff alike (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Support using a kitchen truck

What impressed me was the toilet arrangements. To ensure that the kitchen staff do not catch norovirus or other diseases, some of the kitchen trucks are equipped with their own toilets, separate from those used by the evacuees. It was interesting to see that proper consideration had been given even to aspects like this. This support system is a national government initiative and deployed nationwide.

When I visited, one of the Italian volunteers asked me, “Why would you come here to see this from Japan, when your country rebuilt its expressways in no time after such a huge earthquake?” Apparently, Italy still has bridges that have not been repaired after a disaster 15 years ago. I asked, “How is it you can provide meals so easily?” and was surprised to be met by the reply, “Why wouldn’t we? We’re dealing with people here. There’s no time to lose!” It made me realize that support for the most basic elements of life, such as meals and sleep, is humanitarian aid in its true form. Someone told me that my dream of putting in place a mechanism like Italy’s was wildly impractical, but when Typhoon Hagibis struck in 2019, Marumori Town in Miyagi Prefecture worked with volunteers and nonprofit organizations, using a kitchen truck to make and serve a hearty, vegetable-rich hotpot dish to evacuees without delay. I am convinced that we can bring the Italian model to fruition in Japan.

It has been forecast that Japan has a 70% chance of a megaquake (such as a Tokyo Inland Earthquake or Nankai Trough Earthquake) occurring within the next 30 years. First and foremost, I would like households to ensure that they stockpile supplies, without fail. In addition, to ensure that appropriate dietary support can be provided swiftly in the event of disaster, we wish to put in place a food support mechanism, as well as developing emergency rations and promoting widespread adoption of menus that can be used when disaster strikes.