Tracing its roots back to the private laboratory museum founded in 1932 by Dr. Yoshimaro Yamashina with his own personal funds, the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology is the very cornerstone of avian research in Japan. During the Vietnam War, at the request of the U.S. military, the institute resumed conducting surveys in which leg bands are attached to migratory birds such as herons, which are involved in the transmission of Japanese encephalitis. The institute’s bird banding surveys still continue today, with information provided by not only the 400 or so volunteers currently involved in the program, but also other members of the public. Cutting-edge instruments have also emerged, leading to the establishment of a variety of survey methods. The abundant data accumulated by the institute through its surveys over the decades is helping to speed up ecological investigation.

Special Feature 1 – Mysteries of Migratory Birds Abundant data and cutting-edge instruments are speeding up ecological investigation

composition by Rie Iizuka

Scientific bird banding surveys in Japan have a long history, dating back to a survey launched by the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce (the forerunner of today’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, and Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) in 1924. The surveys were halted in around 1943, due to the war, but later resumed at the request of the U.S. military. Birds were suspected to be involved in transmitting Japanese encephalitis, which was a major problem for the U.S. during the Vietnam War, so the military needed information about herons and other birds migrating from Japan. As Japan was unable to provide any data on avian migration at the time, the U.S. asked the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology to conduct a survey.

Ecological research begins by attaching leg bands

In the 1960s, the institute began to conduct cross-border migration banding surveys with the assistance of a number of Asian countries, namely South Korea, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India.

In 1972, the Environment Agency (now the Ministry of the Environment) embarked on an avian ecology study project that included migratory birds, and commissioned the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology to undertake the study. The institute set up banding survey stations across the country, and began conducting surveys at each station for one to two months a year. These surveys still continue today.

It is almost 50 years since I joined the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology; back then, there were only about 50 people —— referred to as “banders” —— conducting the banding surveys nationwide. Accordingly, in 1979 we launched an initiative to cultivate more banders. This endeavor proved effective, and we now have around 400 banders carrying out this task across Japan.

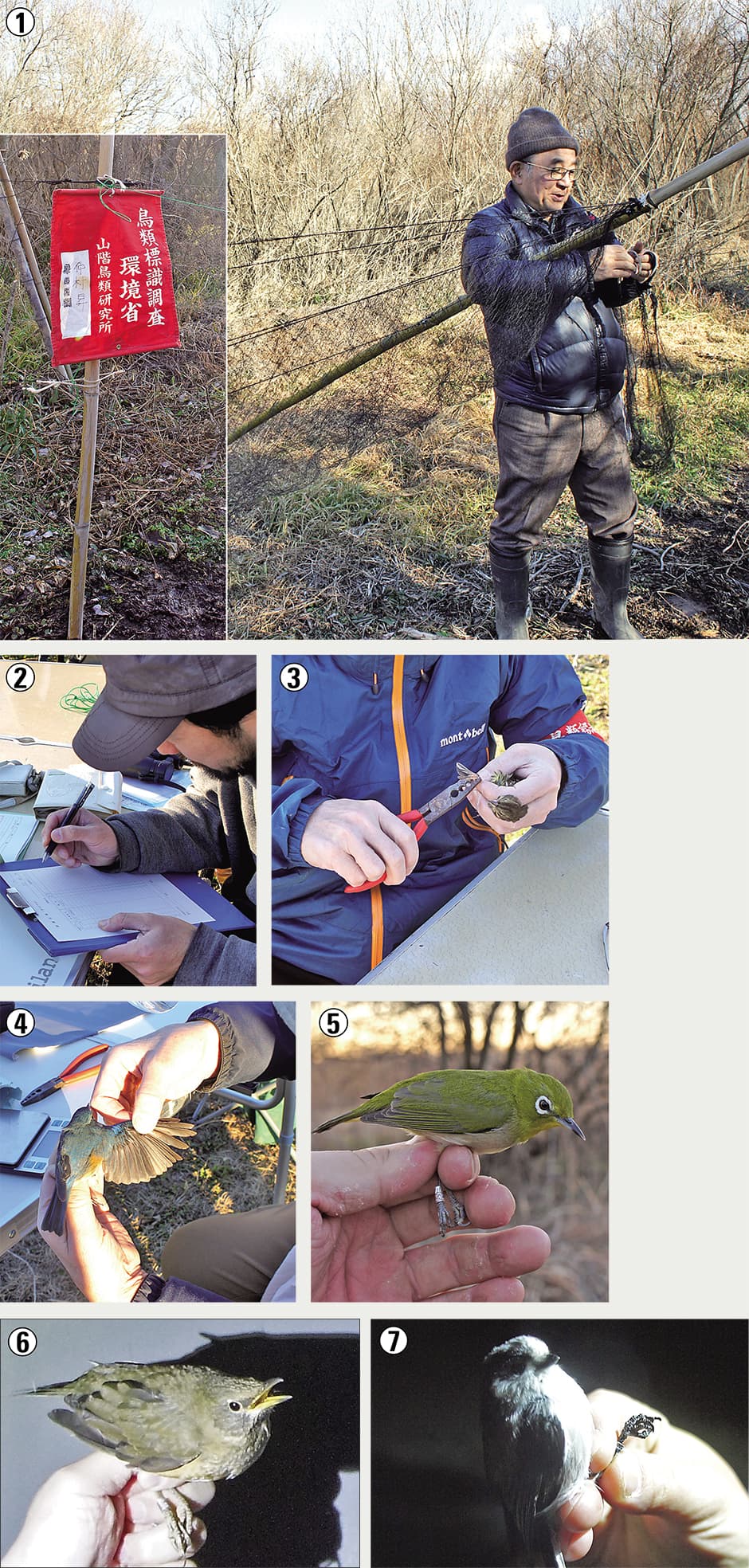

The specific process of banding surveys involves catching birds, identifying their species, sex, and age, attaching a leg band, and recording the details before releasing the bird again (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The leg bands fitted to birdsAlong with an identification number, these leg bands are printed with the words “KANKYOSHO TOKYO JAPAN.” There are 16 sizes of band, used according to the thickness of a bird’s leg.

Those who wish to become banders undergo on-the-job training by accompanying a highly experienced bander. Almost everyone who wishes to become a bander is a birdwatcher who loves birds and is capable of identifying around 100 or 200 avian species while observing them outdoors. However, once you become a bander, you have to identify the bird you have caught and then fit a leg band to it while holding it in your hand. This is surprisingly difficult and even quite a few of those who can identify birds while observing them have trouble identifying them when actually holding one in their hand. We identify birds by size, shape, and call, but when you hold them in your hand, they hardly ever make the kind of sounds they do when outdoors. Their size also seems completely different from when simply observing them, with people often remarking that they are larger or smaller than expected.

Aside from this, we have trainee banders accompany veteran banders on surveys for several weeks each year, in order to learn the techniques for catching birds safely and how to record them according to the required procedure and method. However, as one cannot amass much experience in the space of just a year, the trainees need to spend two to three years accompanying experienced banders on banding surveys.

After this on-the-job training, if a trainee receives a recommendation from the bander who trained them, they take classes at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology and only after that are they officially able to begin their activities as a bander.

The public help to support banding surveys

The training for banders undeniably varies from one country to another, but in Japan, the process is quite rigorous, and it takes about five years before a single bander can conduct banding surveys of all birds. Even so, there are people such as students and retirees who take part entirely without remuneration. This is a good example of the way in which members of the public provide a great deal of support for banding surveys.

In a banding survey, we put up a mist net in a location suitable for surveying birds, then attach a leg band to the birds trapped by the net and record them before setting the birds free again. The mist nets are a tool originating in Japan, and have been used here since the Edo period (1603–1868). Nowadays they are made of nylon, but back then they were made of silk. As they have a fine mesh and are soft, they can capture a large number of birds without injuring them, so these nets have come to be used across the globe. The English name is a direct translation of the Japanese term, while in German, they are known as Japannetz (Japan nets). Today, catching wild birds without permission is prohibited in Japan, so mist nets are not available to the public. The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology lends mist nets to banders, and also provides them with leg bands bearing the name of the Ministry of the Environment. Red flags indicating that a Ministry of the Environment survey is in progress are attached to the mist nets.

Every year, banders send leg band identification numbers and other records of the birds they have released to the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology. We receive records for as many as 120,000–130,000 birds in the space of a year, and the institute has amassed records of more than 6.5 million birds to date. Even when looking beyond birds to the various other kinds of surveys conducted, I believe this must be one of the most extensive and longest-running environmental surveys conducted with the involvement of the public.

Once a leg band has been fitted to a bird, it is possible to shed light on its migration and other aspects of its ecology if the same bird is recovered again, but unfortunately the percentage that is recovered is less than 1%. This rises to several percent in the case of ducks and other species subject to hunting, but those recovered from small birds are almost always incidental, such as cases in which a band happened to be attached to the leg of a bird that died after colliding with a window. Due in part to the increase in the number of banders, the number of birds captured has been increasing of late, and we are starting to see cases in which birds fitted with leg bands are being caught again by banders. At the same time, we have recently begun to receive reports from countries in Southeast Asia, where interest in birds as wild creatures is gradually beginning to grow, so these activities are starting to spread.

The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology launched a survey in its own neighborhood last year. We conduct a monthly survey along the river terrace in the nature observation zone at Yu-Yu Park, which is located beside the Tone River in Abiko City, Chiba Prefecture.

In January this year, we put up 30 mist nets and conducted a banding survey from the afternoon until around noon the next day. Based on the results for the last year, we intend to determine the locations and number of mist nets to put up, and adjust the monitoring conditions to observe fluctuations in the numbers. Around 10 people are involved in this project, including researchers from the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, curators from the Abiko City Museum of Birds, staff from the Natural History Museum and Institute, Chiba, and students and other volunteers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A banding survey at Yu-Yu Park① Catching birds with a mist net is a very effective method and enables surveys to be conducted while ensuring the birds’ safety. Flags indicating that it is a Ministry of the Environment program are attached to the nets. ② A team member silently makes a record. ③ Black-faced Bunting (Emberiza spodocephala). Carefully attaching the right leg band for its leg thickness. ④ Siberian Bluechat (Tarsiger cyanurus). Age is estimated from wing growth, among other features. ⑤ Warbling White-eye (Zosterops japonicus). ⑥ Brown-headed Thrush (Turdus chrysolaus). ⑦ Long-tailed Tit (Aegithalos caudatus). Other birds to which the banders also fitted leg bands that day included Siberian Long-tailed Rosefinch (Carpodacus sibiricus), Meadow Bunting (Emberiza cioides), and Reed Bunting (Emberiza schoeniclus).

Obtaining detailed data on movements using the latest methods

Surveys in which birds are fitted with leg bands have been joined by new methods in the form of geolocators, satellite transmitters, and the eBird website, via which members of the public can send in information. All these techniques are speeding up efforts to shed light on avian ecology.

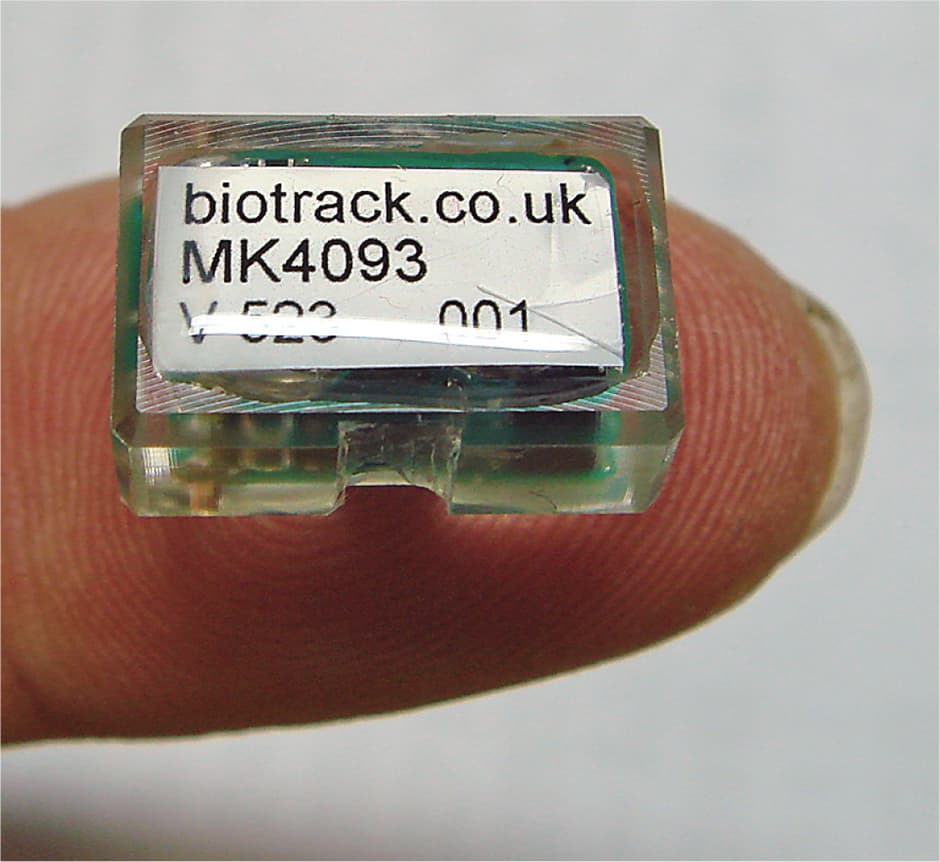

Geolocators are small devices for recording location information. Unlike leg bands, they cannot be attached to a large number of birds, but they have the advantage of providing a variety of data that leg bands alone do not offer, such as insights into migration routes and wintering spots (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A geolocatorA small device consisting of a light sensor and a clock. The light sensor detects sunrise and sunset, which are recorded along with the time. As daytime length varies according to latitude and longitude, this mechanism provides a rough understanding of where the bird is. Its location is calculated from the light information stored in the geolocator.

Also now available are devices that record GPS data and can receive data via satellites and telecommunication lines. While their weight and size limit the range of birds to which they can be fitted, they have helped to expand the options for survey methods, making migratory bird research increasingly interesting.

Long-running banding surveys are starting to provide an overall picture of many species’ movements. Geolocators enable us to obtain more specific data on the movements of birds, albeit for a limited number of individuals.

Additionally, while eBird —— renowned as one of the largest global citizen science projects —— provides information only on sightings, the number of records is immense. A diverse array of people upload observational data on the birds they have sighted at various times, between breeding grounds and wintering spots. Looking at this data, the dynamic movements of birds become apparent.

Side-by-side comparison of the data gathered from leg banding surveys, geolocators, and eBird is adding a new dimension to the investigation of avian migration.

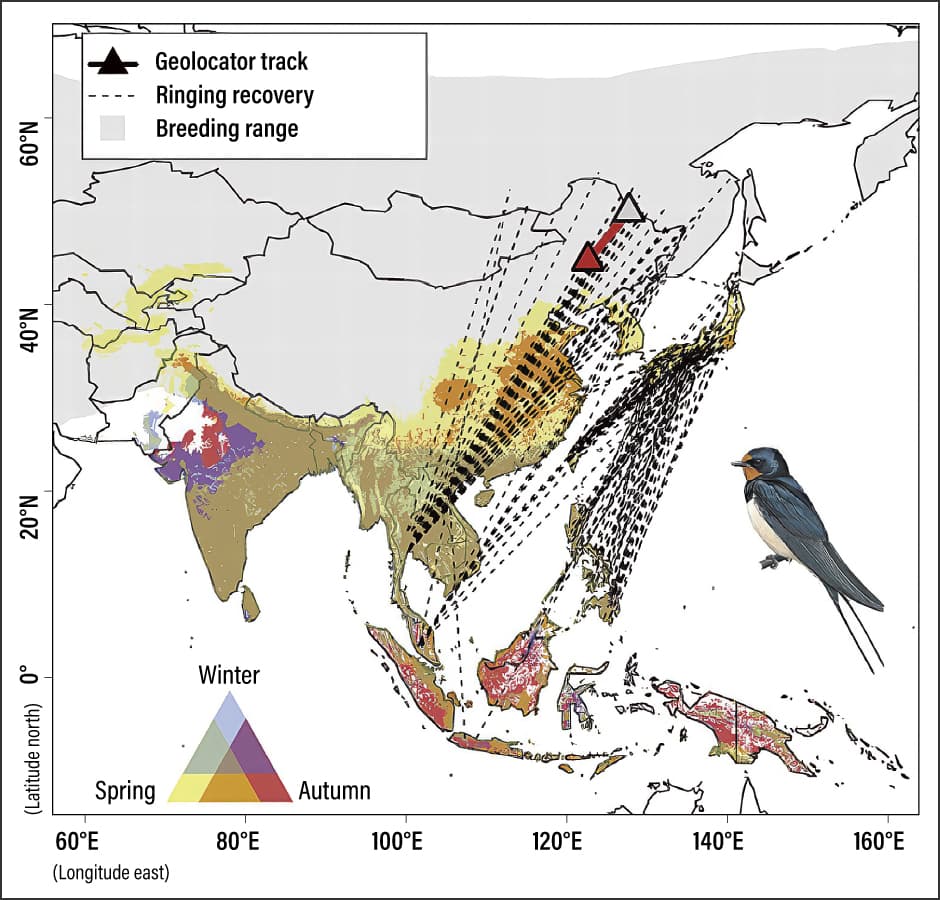

By cross-checking data gathered via these three methods, a study in which I myself participated predicted the distribution of eight species of small birds that migrate through East Asia: the Chestnut-cheeked Starling (Agropsar philippensis), the Siberian Rubythroat (Calliope calliope), the Red-rumped Swallow (Cecropis daurica), the Yellow-breasted Bunting (Emberiza aureola), the Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica), Pallas’s Grasshopper Warbler (Locustella certhiola), Black-naped Oriole (Oriolus chinensis), and Amur Stonechat (Saxicola stejnegeri). We found that the distribution ranges were smaller than in previous predictions.

We also discovered that the Barn Swallows based in Japan use a number of migration corridors, with groups heading to the Philippines or northern Indonesia, and the other to Malaysia, while Thailand is common among Barn Swallows that cross continental Asia (Figure 4). This means that, whereas their distribution range has hitherto appeared extensive when judged by the places where the species are found in spring, autumn, and winter, their breeding grounds and migration routes actually differ according to their group.

Wieland et al. (2020) Global Ecology and Conservation 24

Wieland et al. (2020) Global Ecology and Conservation 24

Figure 4. Understanding Barn Swallow migration using leg banding surveys, geolocators, and eBirdThis diagram summarizes data from Barn Swallow leg bands, geolocators, and eBird. In the eBird data, color-coding is used to indicate locations where the birds were observed in spring, autumn, and winter. This study provided the first visual representation of the approximate movements of Barn Swallows.

A spread in breeding grounds can be seen among other birds. The Rustic Bunting (Emberiza rustica), which overwinters in Japan, originally migrated between Japan and Russia, but for some reason, its breeding grounds have now expanded west to such countries as Norway and Sweden. Once the weather grows colder, they return to spend winter in Japan and southern China. Even though their breeding grounds have expanded, their wintering spots remain the same, and they follow the migration corridors they used when expanding their breeding grounds, which takes them on a detour, increasing the distance they cover when migrating.

In other words, rather than taking the shortest route between their breeding ground and their wintering spot, some birds use unexpected migration corridors due to a variety of reasons, including historical distribution, food availability, seasonal winds, and topography.

The Laysan Albatross still laying eggs at an estimated 74 years old

Banding surveys make a substantial contribution to not only the investigation of migration, but also our knowledge of wild bird life expectancy. We have learned from leg band surveys that although Barn Swallows hatch a large number of chicks, only around 10% of those chicks survive to at least a year old. The life expectancy of most small birds is less than 10 years. In contrast, the Short-tailed Albatross (Phoebastria albatrus) lays only one egg a year and takes as long as five years before it is able to reproduce. We have found that survival strategies vary from one species to another. One migratory bird that is a topic of conversation worldwide right now is a Laysan Albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) estimated to be 74 years old. On Midway Atoll, researchers discovered that an individual to which a leg band was fitted 69 years ago is still laying eggs; since then, the eyes of the world have been on this bird.

As well as telling us the age of birds in the wild, leg banding surveys bring to light fluctuations in numbers. There are many ongoing banding surveys that have been carried out annually in the same place and the same way; if, for example, 1,000 birds are found in one year’s survey, but only 500 the next, we can surmise that something is going on. While fluctuations in bird numbers do occur from one year to another, it is a fact that the overall number of birds is declining. Around half of all avian species worldwide have been on the decline in recent years, and there have been reports in Europe of a fall of 50% or more in the number of birds inhabiting farmland since 1980.

However, it is not easy to answer the question of why this is happening. The fall in the number of Eurasian Tree Sparrows (Passer montanus) is attributed to changes in the roof design of houses that have deprived the birds of places to build their nests. In the case of these sparrows, one can surmise the reason for the decline to some extent, but we have still not found decisive answers as to why so many wild birds are seeing a decrease in numbers. At the very least, I believe we need to keep proper records of what fluctuations are occurring in which species.

The assistance of the general public is essential in our efforts to shed light on the habitats of all birds, not only migratory ones. As well as training banders in Japan, I am keen to work with local people in the Philippines, Thailand, and other parts of Southeast Asia to expand the scope of banding surveys.