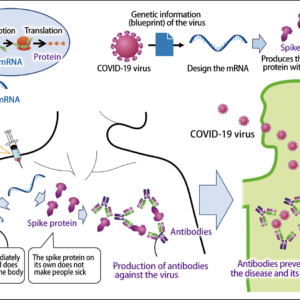

Infectious diseases occur without fail in places where people are crowded together. However, it is impossible to avoid crowded environments at an evacuation shelter when disaster strikes. How, then, should we control the inevitable infectious diseases? Experts say appropriate countermeasures and systems for monitoring signs of outbreaks are crucial. At the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake, experts and a local government infection control team conducted a survey of trends in the outbreak of infectious diseases in Iwate Prefecture and succeeded in minimizing the size of disease clusters. Meanwhile, since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, measures to combat the spread of infectious diseases in crowded environments have become prevalent throughout society. We must not let this experience go to waste.

Special Feature 1 – Recommendations for Scientific Disaster Risk Reduction The key to combating infectious diseases in times of disaster is an extension of measures in daily life

composition by Rie Iizuka

To control infectious diseases, it is essential to have a system for monitoring both the implementation of appropriate measures and the detection of signs of infectious disease outbreaks. In the event of a disaster, medical staff and public health center staff provide health support at evacuation shelters, but it is also desirable to ensure the involvement of personnel with appropriate expertise in order to prevent outbreaks.

As I was in charge of measures against hospital-acquired infection at Iwate Medical University Hospital, I was involved in efforts to combat infectious diseases at evacuation shelters in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Those of us who have been in that position are aware that infectious diseases are absolutely certain to occur in places where people are crowded together, so I believed outbreaks of infectious diseases at evacuation shelters would be inevitable.

Systematically inspecting evacuation shelters

First, allow me to explain the situation at the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Curbing infectious diseases is the job of public health centers, but at that time, some public health center staff had themselves been affected by the disaster, and those who were able to be deployed had their hands full checking the identities of disaster victims and confirming people’s survival, so undertaking their normal duties was out of the question (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Otsuchi Town, Iwate Prefecture on March 17, 2011The tsunami that inundated the town was as tall as a three-story house. The entire prefecture suffered power outages lasting several days and approximately 50,000 people were forced to stay in evacuation shelters.

At the same time, hospitals did not have enough capacity to admit even a few dozen patients if an infection cluster emerged at an evacuation shelter. As communications and transport infrastructure were cut off, we had no idea what the situation was at evacuation shelters in the coastal area that had suffered immense damage, so I decided to go and ascertain the current situation and deal with any outbreaks of infectious disease. Accompanied by a pharmacist involved in infection control measures, I systematically inspected evacuation shelters in Iwate Prefecture, working from north to south. Starting on March 14, three days after the disaster struck, we began to make the rounds of evacuation shelters with a capacity of at least 100 people. However, I remember how limited our activities were, as we were not staff from the public health center, or members of a Disaster Medical Assistance Team (DMAT), or even physicians sent from other prefectures to provide support, just two people without any authority, conducting a survey of outbreaks.

Depending solely on our business cards from Iwate Medical University Hospital, we continued to carry out our survey, advocating that it was needed “to protect the survivors from the risk of infectious disease.” In April, news of our activities reached the department in charge of public health, and the decision was taken to make our work official, as both the National Institute of Infectious Diseases and the prefecture needed information. There were limits to what a university hospital could do when it came to undertaking infection control across an extensive area amid the various constraints experienced in the wake of a disaster, and we were keenly aware of the need to collaborate with local governments, so the launch of the Iwate Disaster Medical Support Network’s Iwate Infection Control Assistance Team (ICAT), headquartered at Iwate Prefectural Office, represented a major step forward in our efforts to implement measures to combat infectious disease.

When we visited evacuation shelters, the first things we investigated were the sanitation environment and the clothing, food, and living space conditions. Where infrastructure such as water supply, sewerage, electricity and fuel has been hard hit and their restoration takes time, the environment becomes less hygienic the longer access to such infrastructure is cut off. The basic foundations of daily life therefore crumble, bringing a heightened risk of infectious disease.

The measures that suffice in daily life are not enough

Virtually the whole of Japan is covered by water supply and sewerage facilities, and this, combined with proper waste management ensures a safe water supply and sanitary environment. We take this for granted in our daily lives, so people’s knowledge of measures against infectious disease in an emergency could not really be described as adequate. While everyone does take some measures at evacuation shelters, the measures that suffice in normal daily life are not enough for an environment in which random people are crowded together for a lengthy period.

The terrible reality of this truly hit home to me at one evacuation shelter, where, despite the provision of alcohol-based hand sanitizer and posters exhorting people to use it to clean their hands, I saw people then sharing a towel to dry their hands. Nowadays, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought widespread awareness that alcohol-based hand sanitizer should be left on the hands, and that sharing towels with other people increases the risk of infection. It would be fair to say that this is exactly what we have been aiming for with our aspiration to make basic measures against infectious disease a part of daily life. The knowledge and customs acquired in this way will help to mitigate the health risks in the event of disaster.

The ways in which food is prepared also bring a risk of infection. As is familiar to most people in Japan from school lunches and the like, when serving meals to a large group of people, one should wear hygienic clothes and gloves, and disinfect the utensils before use. However, a lack of supplies at some evacuation shelters meant that such measures could not be taken, and there were even shelters where a storage shed accessed by people wearing outdoor shoes was used as a kitchen (Figure 2). Emergency meal distribution by volunteers was also common in every area. While people were grateful for this heartwarming support, the fact was that it entailed many infection risks.

Figure 2. An example of a storage shed being used as a kitchenA muddy mower and hoe were stored at the back, without being partitioned off. Rice was cooked in a gas-fueled rice cooker placed directly on the floor, on which people walked with outdoor shoes. As there was no water supply to the shed, water was provided via a long hose run from a tap outside the toilet.

We decided that the objective of our activities was to reduce these infection risks by providing appropriate information, so that people could arm themselves with appropriate knowledge, enabling as many people as possible to continue leading healthy lives at evacuation shelters and thereby supporting them to work toward recovery.

The basic infection control measure at ordinary evacuation shelters is prevention. When signs of an outbreak are observed, infection control experts with knowledge and practical experience are needed to identify risks at as early a stage as possible and provide appropriate support to facilitate improvements, supervise the distribution of hygiene supplies and the procurement of preventive drugs.

It is a basic assumption that the infrastructure and hygiene situation at an evacuation shelter will not be adequate in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, so implementing the full range of infection control measures will not be possible. However, even where there are constraints on the environment or resources, creativity can be employed to devise the best possible measures tailored to the actual situation on the ground. Conscientiously implementing such steady efforts will help to curb infectious diseases.

Immunization is an effective means of preventing infection in the event of disaster

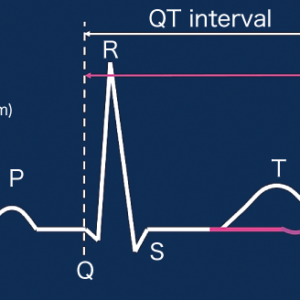

The outbreak of infectious diseases occurring after a disaster is broadly consistent, as can be seen in many cases both within Japan and overseas. Immediately after a disaster, infectious diseases caused by injuries are most prominent (Figure 3). Injuries caused by treading on or catching one’s hand on debris or nails, or walking through mud with injured feet lead to a risk of tetanus or gas gangrene. As such infections can even pose a deadly risk, it is necessary to have even minor injuries treated with antiseptic and the like, or to seek assistance from a medical care professional, rather than ignoring an injury and assuming you can put up with it because it is not a major one. You must also remember that there is an incubation period even for infectious diseases caused by trauma.

Source: Japanese Society for Infection Prevention and Control (ed.), Guidance on Infection Control Management in the Areas Affected by Large-scale Natural Disaster

Source: Japanese Society for Infection Prevention and Control (ed.), Guidance on Infection Control Management in the Areas Affected by Large-scale Natural Disaster

Figure 3. Infectious diseases after a disaster and time of outbreakThe first to emerge are infectious diseases specific to disasters, followed by infectious diseases associated with living conditions in evacuation shelters, and finally a deteriorating sanitary environment.

The next thing one tends to see at evacuation shelters is respiratory tract infections such as influenza, pneumonia, and, among children, hand- foot-and-mouth disease. COVID-19 is also among them. These diseases spread via droplet infection, and can be prevented through the use of masks, handwashing, and disinfecting any surfaces on which droplets from sneezes and coughs have landed. Another very effective means of preventing infection in the event of disaster is to ensure you get up to date with immunizations before disaster strikes.

Once support begins to be provided to disaster-stricken areas, the incidence of infectious diseases related to food rises. The most common conditions seen at evacuation shelters are diarrhea and vomiting, which are caused in almost all cases by norovirus infections. The measures required include disinfecting hands before cooking or eating, keeping kitchens in a hygienic state, using disposable or sterilized tableware, avoiding the preparation of food in advance, as far as possible, and not storing leftovers.

While certain patterns can be seen in outbreaks of infectious diseases, no matter where a disaster might have occurred, these observations are based on no more than empirical experience and have not been verified scientifically. This is because scientific verification and gathering comparable data are extremely difficult in the aftermath of a disaster. I believe the priority is to gather reports of cases each time a disaster occurs, steadily build up data that can provide empirical rules, look at what kind of patterns or trends emerge, and identify points in common so we can take steps to deal with them.

When I was going around the evacuation shelters in Iwate Prefecture and gathering information, Professor Koki Kaku of National Defense Medical College suggested I could use the internet to carry out a surveillance study to identify incidence trends. When Kaku was posted to Southeast Asia to conduct a survey of the damage caused by a tsunami, there were outbreaks of diarrhea, so he conducted a surveillance study to identify the location and scale of each outbreak. Based on this experience, he had developed a database app that enabled data to be entered in a standard format via the internet from any location. That is how I came to use the app in an effort to gather data efficiently.

Telecommunications carriers cooperated by lending us 50-60 tablet devices, which we began distributing to evacuation shelters from April 7, and had them enter their data regularly. The questions asked about symptoms such as fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Users could also enter details of any signs and symptoms caused by infectious diseases. We plotted the entered data on Google Maps and enabled overall and shelter-specific trends in outbreaks of infectious disease to be displayed in the comments field (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Google Map with plotted dataFig. 4 shows where the tablets were located and lists the outbreaks at each evacuation shelter. Data was updated on a daily basis. The map also shows a summary of outbreak occurrences at all monitored shelters in Iwate Prefecture.

Viewing evacuation shelters with an expert’s eye is crucial

Our monitoring of trends in outbreaks of infectious disease at evacuation shelters using the surveillance system continued until August, ending when the evacuation shelters closed or were scaled down due to evacuees moving into temporary housing. The visits by ICAT members had a synergistic effect in that we were able to identify signs of infectious disease outbreaks promptly and respond to them swiftly. Accordingly, we were able to keep disease clusters smaller (two outbreaks of about 30 people) than in neighboring prefectures.

The U.S. has the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which conduct surveillance studies in the event of disaster and have built databases. In contrast, Japan builds teams and mechanisms tailored to the situation each time a disaster occurs, which are then disbanded once the situation has been resolved.

However, given that infectious diseases never go away, I believe building up these responses each time will result in the infrastructure of infection control measures and prevention of infectious diseases being built up little by little. In Iwate Prefecture, the prefectural assembly approved the establishment of ICAT as a permanent, official organization in June 2012. One positive outcome was that many people turned their attention to ICAT’s activities.

The national government also became aware of our activities and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s Disaster Management Operation Plan (July 2017) stated that local governments of disaster-affected areas would be required to work with the Japanese Society for Infection Prevention and Control and other bodies and swiftly dispatch an infection control team. This is a groundbreaking development and I hope that legislation regarding infection control measures will be introduced in the future.

Viewing evacuation shelters with an expert’s eye is crucial to curbing infectious diseases in the event of disaster. It is necessary to have on the ground not only physicians and nurses to treat people, but also experts whose role is to carry out monitoring to prevent infectious diseases and check that there are no lapses in the hygiene situation. Infection control means enhancing the overall environment from a macro perspective.

At the same time, the silver lining to the dreadful COVID-19 pandemic has been an increase in infection prevention literacy among the public. Mask-wearing has become normal in places where large groups of people gather, and people are unlikely to feel discomfort about having their temperature taken and being asked to undergo other health checks before entering an evacuation shelter.

If any high-risk individuals are identified, they can be isolated as a precautionary measure or have other restrictions imposed on their behavior in order to prevent them from infecting those around them. If a disaster occurs, all that needs to be done is to reinforce such routine infection control measures.

The measures that combat infectious diseases in times of disaster are an extension of the steps taken in daily life, so we must maintain an awareness of the need to do our very best, even when the situation is not ideal