Our organs all have their own biological clock, which maintains biological activity over a cycle of around 24 hours. Accordingly, not only what we eat and how much of it, but also the chronological perspective of what we eat and when is an important consideration. The timing at which we should consume nutrients varies according to age and lifestyle, as well as whether one is a morning or a night person. As our lifestyles have changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, let us take another look at them from the perspective of the science of chrono-nutrition.

Special Feature 1 – Nutritional Science for a New Age The interactions between our body clock and food — The importance of what we eat and when

composition by Yumi Ohuchi

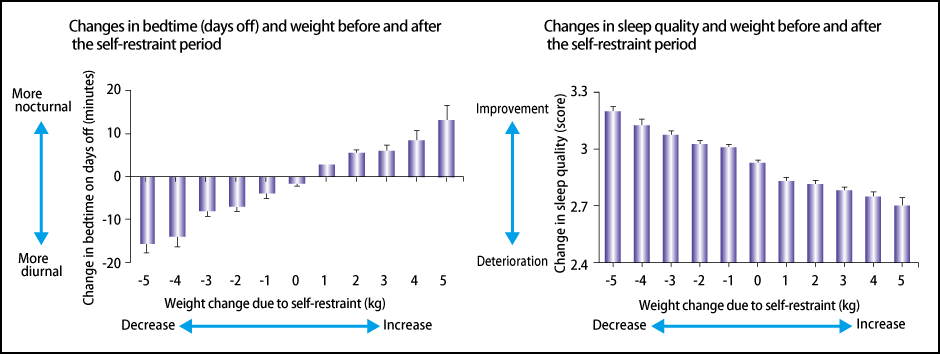

With the COVID-19 pandemic continuing to spread, our lifestyles are changing rapidly. We conducted a questionnaire-based survey of approximately 30,000 people about changes in the rhythms of their lifestyles and their weight during the state of emergency, when people were asked to refrain from going out. I will describe more about the study below, but one finding was that there had been an increase in the number of people with a more nocturnal lifestyle (going to bed late and getting up late) on both working days and days off, particularly among younger people from their 10s to their 30s. This is thought to be because social constraints such as the need to commute to work or school at particular times were lifted. We also observed a tendency toward an increase in weight among those who adopted a more nocturnal lifestyle, while those who adopted more diurnal lifestyle (going to bed early and getting up early) saw their weight decrease (Figure 1). Why do changes in the rhythms of our lifestyles affect our bodies? It is because our bodies have their own internal clock, which maintains biological activity by creating a rhythm that functions on a cycle of about 24 hours.

Figure 1. Relationship between weight change and sleep during the self-restraint periodThere was a tendency for those who became more diurnal to have lost weight and those who adopted a more nocturnal lifestyle to have put weight on. Those whose weight increased were also observed to have experienced a deterioration in sleep quality.(https://www.waseda.jp/top/news/70080)

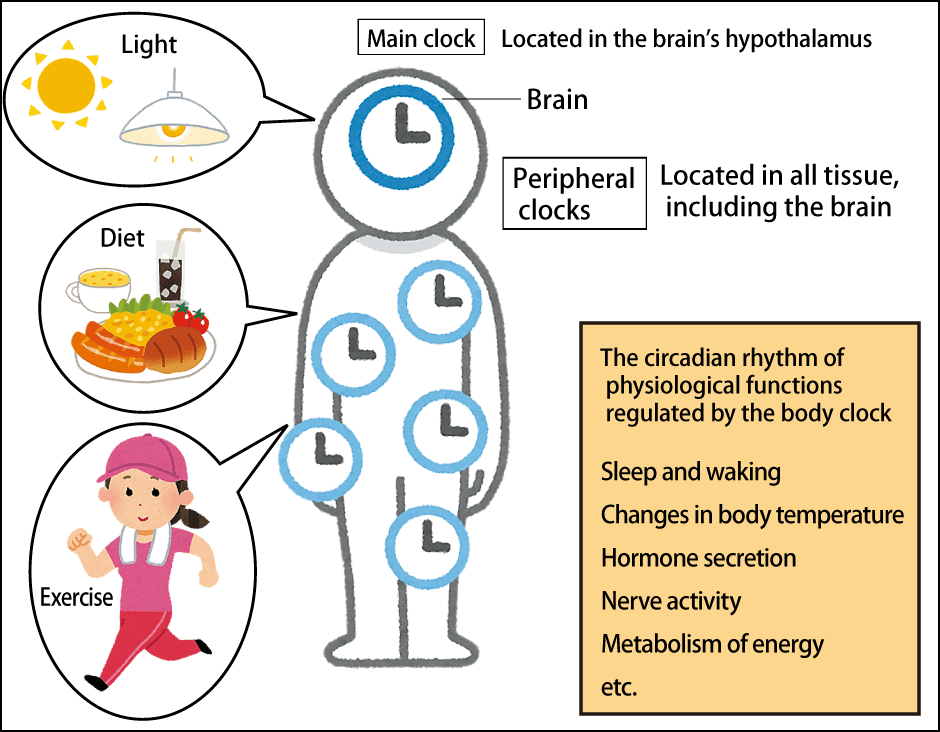

Our body clock is regulated by the clock gene, which is found in the cells of all our organs and tissues. The main clock is located in the brain’s hypothalamus, which regulates the rhythms of the peripheral clock genes throughout our body like the conductor of an orchestra.

The biological clock in each organ has its own function, with food digestion, absorption, metabolism, and excretion controlled by the biological clocks in the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, liver, kidneys, and pancreas, among others. Accordingly, not only what we eat and how much of it, but also the chronological perspective of what we eat and when is an important consideration. Our research team is therefore advocating the science of chrono-nutrition—the study of the interactions between our body clock and food/nutrition.

The two interactions between our body clock and food

There are two aspects to the interactions between our body clock and food. One is the action of food on the body clock. The human body clock cannot keep to a rhythm of precisely 24 hours and while there are differences between individuals, some people end up out of sync because of working to a somewhat longer cycle. If this discrepancy becomes a chronic issue, people can find themselves effectively suffering from ongoing jet lag. In addition, changing the rhythms of our lifestyles by going to bed and waking early on working days, but going to bed and waking late on days off can cause “social jet lag”. This kind of disarray in the body clock has adverse impacts on health, causing sleep disorders and obesity.

Synchronizing the body clock with actual clock time is crucial in order to eliminate this jet lag. Light stimulus is one means of effecting this synchronization: it is well known that exposure to light in the morning can reset the main clock. In fact, diet and exercise also have important functions as synchronizers (Figure 2). Tests on mice have shown that continuing to feed them at set times resets their peripheral clocks. As such tests have also shown that breakfast brings the body clock forward, while late dinner pushes it back, these meals are likely to have similar effects on humans. In other words, skipping breakfast or eating dinner late in the evening could potentially disrupt the body clock, so it is important to eat three meals a day at the right time.

Figure 2. Body clock mechanismsThe main clock and peripheral clocks regulate the circadian rhythm of physiological functions. While discrepancies between real time and the body clock do arise, morning light, breakfast, and exercise reset the body clock.

Another interaction is the effect of the body clock on eating, as the timing of meals determines the functions of nutrients. For example, everyone feels empirically that overeating at dinner or eating late at night causes us to put on weight. While we might be less active after dinner and therefore consume less energy, there are reports based on findings from experiments suggesting that we are more prone to storing fat at night than in the morning, due to the involvement of the clock gene. When it comes to sugars, too, we know that blood glucose levels are less prone to rise in the morning and more prone to doing so at night, even when exactly the same meal is eaten. This is because the effects of insulin, which stabilizes blood glucose levels, are higher in the morning and decline at night. More specifically, whereas sugars consumed in the morning are swiftly supplied to cells as energy, those consumed at night are not all supplied to cells and the excess sugars end up being stored as fat.

We also know that consuming protein—essential to the maintenance of muscle, organs, and tissues—in the morning is most effective for muscle synthesis. Conversely, while consuming an appropriate amount of protein at night is fine, any excess protein consumed at night will not be used for muscle synthesis and will simply be excreted, thereby placing a burden on the kidneys.

Nutrients’ effects differ according to when they are eaten

There are findings from various studies concerning differences arising from the timing at which functional components believed to be healthy are consumed. For example, sesamin, a fat-soluble component of sesame, is believed to reduce cholesterol through antioxidant action. Our research found that when sesamin was consumed in the morning, cholesterol synthesis in the liver and the expression of enzymes involved in its metabolism was lower than when sesamin was consumed in the evening, demonstrating that the cholesterol-reducing effect is higher in the morning.

We also conducted a study in healthy seniors concerning the consumption of Jerusalem artichoke powder, which contains a water-soluble dietary fiber called inulin. Water-soluble dietary fiber is believed to assist in improving the intestinal environment, because it is viscous and suppresses increases in blood glucose levels by slowing the absorption of sugars, as well as serving as food for bifidobacteria and other good bacteria. An improvement in constipation was observed in the group that consumed Jerusalem artichoke powder before breakfast, when compared to those who consumed it before dinner. In addition, the powder’s effect in suppressing rises in blood glucose levels was higher among the pre-breakfast group, with rises in blood glucose levels also curbed after lunch and dinner. Looking at changes in the intestinal microbiota as indicated by increases in bacteria in the phylum Bacteroidetes and decreases in those in the phylum Firmicutes, a bigger change was observed among the pre-breakfast group. It has been reported that people who are obese and hyperglycemic have low levels of Bacteroidetes and high levels of Firmicutes, so an increase in Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Firmicutes is generally regarded as a positive change. As bacteria, including enteric bacteria, do not have a biological clock, regulation by the gut’s biological clock is thought to be involved in changes in the microbiota.

In addition, there are findings from studies showing that higher blood concentrations of lycopene and DHA result when they are consumed in the morning. This is thought to be because bile, which absorbs fat-soluble substances, accumulates in the gallbladder while we are sleeping, making it more easily secreted in the morning. Given all these facts, we know that breakfast is very important, because it not only resets our body clock, but also has various positive effects on the body. However, not only do people tend not to eat as much for breakfast as for lunch and dinner, but also quite a few people do not eat breakfast at all. Accordingly, we recommend that people eat a good breakfast and increase the amount of protein that they consume at breakfast.

Consuming protein at breakfast is key

A person weighing 60 kg is said to require a protein intake of about 60 g per day, but protein consumption has been on the decline in recent years. In particular, there is data showing that protein consumption tends to be skewed toward dinner, with the lowest amount being consumed at breakfast, which is actually when the greatest muscle maintenance effect can be expected. We have received the same impression from the numerous studies that we have conducted. Accordingly, people should aim to consume 20 g of the protein they need at breakfast and make the rest up at lunch and dinner. I often say that eating a lot at dinner is wasteful and it is better to eat a large amount at breakfast instead.

The foods from which one’s protein intake comes are also key. When we compared meat, fish, and soy products as part of our research, we did not find a great difference between them in terms of maintaining muscle. However, as meat also contains fat, we must be careful not to eat too much. The isoflavones in soy products improve blood flow, so it is probably wise to make a conscious effort to include them in our diet. If you are busy in the morning and do not have time to cook, one way of increasing protein intake is to use soymilk or dairy products such as milk and yogurt. Milk contains the calcium required for bone formation. However, it is believed that calcium absorption increases from early evening into the night, assisting in bone formation. Accordingly, if you wish to maintain muscle, it is advisable to drink milk in the morning, while if maintaining bone health is your objective, it is better to drink it in the evening. Drinking milk at night is also said to improve sleep quality. However, as milk contains milk fat, we recommend that people drinking milk in the evening or at night choose low-fat or fat-free varieties.

We are also conducting research focused on fluctuations in blood glucose levels. When people spend a longer time with empty stomachs, due to skipping breakfast, for example, their blood glucose levels rise sharply when they do eat. Rapid rises in blood glucose levels are called blood glucose spikes. They damage blood vessels and cause arteriosclerosis to progress, thereby increasing the risk of myocardial infarction and cerebral infarction. Ignoring blood glucose spikes is also said to make people more prone to developing diabetes.

At the same time, it has emerged that the first meal of the day also affects blood glucose levels after the second-meal. This is called the second-meal effect. More specifically, curbing the rise in blood glucose level at breakfast also suppresses the blood glucose level at the subsequent meal. The blood glucose level suppression effect observed in the aforementioned study of Jerusalem artichoke powder is due to this second-meal effect.

However, the second-meal effect is only sustained for four or five hours. Accordingly, if you ate breakfast at 07:00, you should ideally eat lunch at 12:00 and dinner at 17:00, but conventional lifestyles tend inevitably to result in a longer gap between lunch and dinner. To make things worse, there is already a greater tendency for blood glucose levels to rise at night.

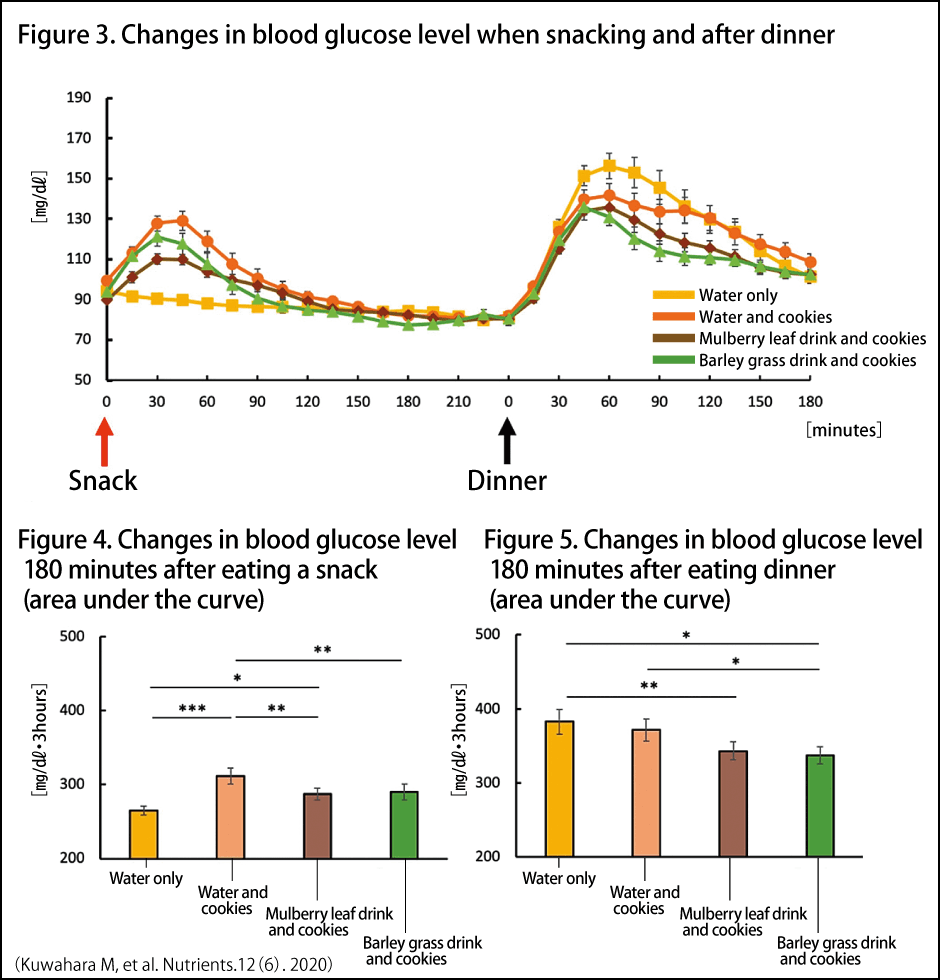

Accordingly, we conducted an experiment in which subjects ate lunch at 12:00 and the same meal at dinner, and had some eat cookies with 150 kcal as a snack between 17:00 and 18:00, while others did not. We then looked at whether there was any difference in blood glucose levels between them. The results showed that the rise in blood glucose levels after dinner was curbed in those who ate the snack. When we then had some subjects drink a barley grass drink or mulberry leaf drink containing dietary fiber when they ate their cookies, we found that there was an even greater effect in suppressing the rise in blood glucose levels after dinner (Figures 3, 4, 5). Until now, snacking has been regarded as a bad thing, but I believe that positive snacking can actually be good for our health if we are mindful of the time at which the snack is consumed, as well as its nutrients and calorie content.

While blood glucose levels rise for a time after the snack, blood glucose levels after dinner stayed lower than among the water-only group. In addition, the rise in blood glucose levels was lower among those who consumed a drink containing barley grass or mulberry leaf along with their cookies than among those who consumed the cookies alone.

Personalized chrono-nutrition

Let us return to the survey mentioned at the beginning. The survey subjects were users of the diet management app Asken (developed by asken Inc. ) and were therefore comparatively diet-conscious. To start with, we hypothesized that weight would decrease, because people had become more nocturnal on both working days and days off, thereby eliminating social jet lag—that is to say, body clock disruption. However, our results showed the opposite.

Analyzing the responses of those who had put on weight and those who had lost it, we discovered that both groups had seen increases in the duration of sleep and an improvement in social jet lag. However, compared with those who had lost weight, most subjects who had put on weight responded that they had eaten more snacks and experienced reductions in sleep quality and physical activity. As such, it appears that, rather than eliminating sleep deficiency and social jet lag, changes in whether people were diurnal or nocturnal and consequent changes in physical activity, snacks, and sleep quality led to short-term weight changes.

It would therefore seem that a diurnal lifestyle has positive effects on the body. Nevertheless, one cannot simply say that a nocturnal lifestyle is bad. Certainly, a nocturnal lifestyle has been reported as having many disadvantages, such as making people more prone to obesity and lifestyle-related diseases, and also more prone to reduced performance at work or school. However, I believe it is important to acquire lifestyle habits that have the same effects as a diurnal lifestyle.

Chrono-nutrition does not advocate a one-size-fits-all model, such as saying that everyone must eat breakfast at 07:00. Some people are diurnal, while some are nocturnal and others have to keep irregular lifestyle patterns, due to shift work. The timing at which we should consume nutrients also varies according to age and lifestyle. I believe that, just as cancer treatment is personalized, it is important to offer chronologically focused health guidance tailored to the feeding, activity and sleep rhythms of each individual’s lifestyle.