Instinctive anxiety or fear when faced with unfamiliar risks is only natural, and it is perhaps inevitable that theoretical explanations do not get the message across. One factor contributing to this is the discrepancy between the risk perception of the public and the risk assessments of experts, who hitherto thought that providing scientifically accurate knowledge and information was sufficient to ensure full awareness. In light of this situation, risk communication needs to be based on mutual trust between the person delivering the message and those receiving it.

Special Feature 1 – Is Science Communication Good Enough? Why do scientific risk assessments fail to resonate with people?

composition by Yumi Ohuchi

Telling people about risk elicits anxiety and other strong reactions, and can sometimes even result in social confusion. We have seen a multitude of examples in the past, in relation to such issues as dioxins, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), avian influenza, and the dispersion of radioactive materials in the wake of the accident at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

The general definition of risk states that it is composed of the seriousness of an undesirable outcome and the probability of that undesirable outcome actually occurring. For example, the risk of death due to a traffic accident consists of the seriousness of the undesirable outcome, namely death, and the probability of a fatal accident occurring. The more serious the undesirable outcome or the higher the probability of the undesirable outcome’s occurrence, the higher experts rate the risk, and these experts believe that the public will take steps to avoid such risks. However, do people actually perceive risk and judge avoidance behavior in the same way as the experts?

For example, in 2001, when cattle infected with BSE were discovered in Japan for the first time, there was public panic, because people infected with the pathogen could develop variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), which is fatal. This panic dealt a huge blow to the livestock industry and restaurants specializing in grilled meat and beef bowls. Amid this situation, the Food Safety Commission of Japan conducted a risk assessment and presented calculations showing that the risk of developing vCJD in Japan was 0.9 patients in the entire population even in the worst-case scenario, yet consumers continued to abandon beef in droves. Thus, people may overreact to a low risk or, conversely, fail to react to a high risk that they estimate to be low. This is because people perceive and react to risk intuitively.

How do people react to risk?

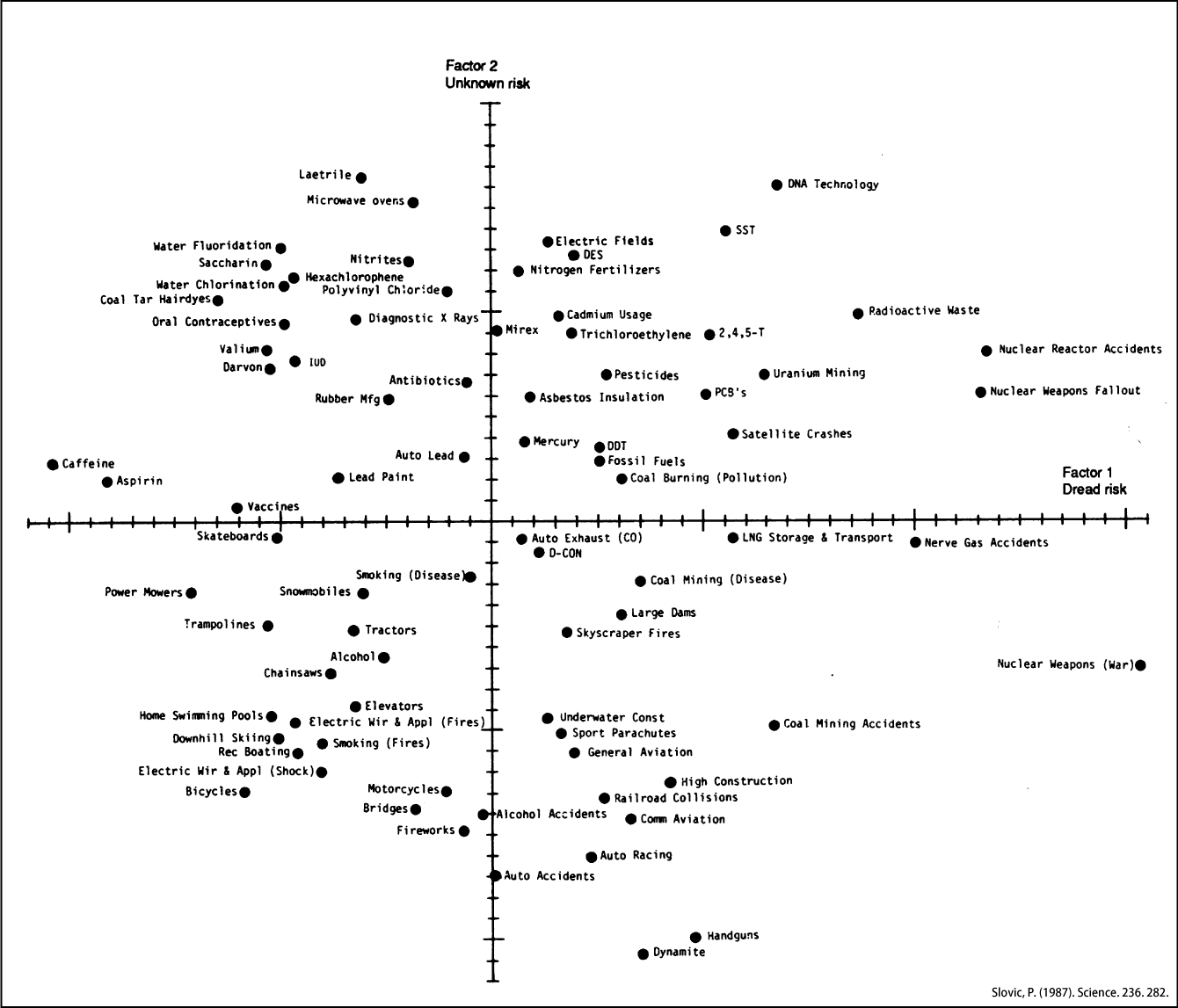

In risk perception research, the two-factor model of dread risk and unknown risk is regarded as the basis for these intuitive reactions. Each of these factors is composed of the following elements and the more factors that apply to the risk in question, the stronger a person’s intuitive reaction will be.

| · Dread risk:Fatal consequences, potential for global catastrophe, hard to control, fear of adverse consequences for future generations, inequitable distribution of risks, and involuntary exposure. |

| · Unknown risk:Delayed effects, difficulty of observation from the outside, imperceptibility to affected individuals, unfamiliarity, lack of scientific understanding, and novelty. |

The aforementioned disease BSE was fatal, had the potential for catastrophic consequences on a global scale, was hard to control, and involved involuntary exposure, as those who were exposed would not have eaten the beef if they had known it was infected with BSE. In addition, onset of the disease occurs several years after infection, people cannot tell whether or not beef is infected with BSE merely by looking at it, and the process by which humans become infected and symptomatic is not well understood in scientific terms. Thus, many of the elements in the two factors are applicable to BSE. It would be fair to say that COVID-19 is similar to BSE in that respect. It can be fatal and has the potential to spread across the globe simply in the course of leading our everyday lives. In addition, its status as a new virus makes it hard to control, as vaccines are not yet widely available and therapeutic drugs are yet to be developed. Furthermore, there is an incubation period of around two weeks before people become symptomatic and people cannot tell merely by looking whether or not someone is infected. Let us look at an example showing the positioning of various hazards in relation to the two factor axes (Figure). I believe COVID-19 might be somewhere in the same area as nuclear reactor accidents.

Figure. Positioning of various hazardsIt is believed that the greater the number of elements applicable to dread risk and unknown risk, the stronger the reaction demonstrated by people will be. Attitudes toward dread risk and unknown risk also differ in different time periods and from one individual to another.

It is said that when the unknown risk features are particularly strong, even if the number of victims is still low at present, it gives people the sense of a future catastrophe and generates a more negative reaction. Immediately after the accident at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, then Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano said that there would be no “immediate effect,” meaning that the public would not be exposed to high doses of radiation and that he therefore wanted them to deal with the situation calmly. However, contrary to his intention, this had the effect of adding fuel to the fire, which is thought to be because the situation constituted an unknown risk.

Positioned as the exact opposite kind of risk to this are bicycles. The actual number of bicycle-related accidents is 80,473 and the number of fatalities while riding a bicycle is 433 people per year (2019, National Police Agency: Statistics about Road Traffic), which is certainly not a low risk. The reason why people nevertheless do not mount campaigns to boycott bicycles is probably because few of the two factors are applicable: bicycles are not a complicated form of transport in scientific terms and people have a choice about riding them, do not have the impression that riding them is fatal, can control them by operating the brakes, and are familiar with them.

Another important perspective in learning about how people perceive risk is the two thought systems. In simple terms, living in our heads we have two decision-makers (System 1 and System 2), both of whom receive risk information. System 1 is instinctive and based on emotion, making decisions quickly, effortlessly, and intuitively, whereas System 2 is analytical and based on logic, taking time, using the brain, and reasoning to make decisions (Table 1). It would be fair to say that the aforementioned two factors are the product of System 1, while experts’ risk assessments are the product of System 2.

| System 1 (experiential system) | System 2 (analytical system) |

| Instinctive | Analytical |

| Based on emotion | Based on logic |

| Quick, effortless, and intuitive judgments | Taking time, using the brain, and reasoning to make judgments |

| Forthright reaction | Cautious reaction |

| Understanding reality via specific video, still images, and individual examples | Understanding reality via abstract figures, statistics, and generalities |

Table 1. System 1 and System 2In psychology, the System 1 and System 2 concept is called the dual process theory. These two cognitive systems work in harmony not merely in relation to risk, but rather in respect of almost all situations.

Looking which of these thought systems is stronger, System 1 instantly brings about action in our daily lives. Over the long history of human evolution, we have principally led a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In the course of this lifestyle, humans needed to make swift, if imprecise decisions about the constant stream of risks with which they were faced, such as when an animal was attacking them. The primacy of System 1 in our daily lives is thought to be the result of our having survived through our reliance on it. Of course, it is an essential thought system for avoiding risk even today. That is why, even when we understand things logically via System 2, we do not always act accordingly. This is what we experience with attempts to stop smoking or go on a diet —— that feeling of “I understand, but I just can’t stop.”

The crucial feature of System 1 here is that it understands reality from specific visual information and individual examples. For example, the huge number of fatalities and refugees resulting from the Syrian Civil War was reported worldwide. However, people across the globe were passive about providing aid for victims. But the minute that global media published a photograph of the body of a three-year-old refugee boy washed up on the Turkish coast, aid began pouring in. One case in Japan is still fresh in my memory. After an elderly driver lost control of his car in Ikebukuro, hitting and killing a mother and her child, photographs of the victims and their backgrounds were featured heavily in the media. The attention this drew among the public led to an increase in the number of elderly people voluntarily surrendering their driver’s licenses. The death of the comedian Ken Shimura from COVID-19 was a huge blow to people. Cases of this kind involving specific people whom we can see have a more powerful impact on us than logical data. It would be fair to say that this is probably why the influence of mass media is so great.

What does successful risk communication look like?

Thus, there is a discrepancy between the risk assessments of experts and the risk perception of the general public. It is necessary to plan risk communication —— the communication of risk information among interested parties —— based on this understanding. However, risk communication in Japan is mainly carried out by experts in risk assessment, who are not conversant with risk perception. Risk communication should, by rights, be carried out by an intermediary positioned between the people who carry out risk assessments and the people who receive them.

Experts think that risk communication has been successful if it results in an accurate understanding of their risk assessment among the general public. However, this is only part of risk communication. In a definition widely used today, the U.S. National Research Council (NRC) describes risk communication as “an interactive process of exchange of information among individuals, groups, and institutions.” In other words, it is not a one-way process in which the expert, government, or other party providing risk information conveys knowledge to the public or other recipients, but rather a two-way process in which the recipients provide feedback about their thoughts, feelings, and the things they want to know, and the party delivering the information responds to this feedback. The purpose of risk communication is not to bring people around to the information provider’s way of thinking or to build consensus among the parties. Of course, it is best if consensus can be built, but it is virtually impossible to ensure that people with different standpoints and values will give the same answer. I am sure that readers are keenly aware of this, given what we have seen amid the current pandemic, with people who have seen a sharp drop in income calling for economic recovery, while those who have not have been lobbying for lockdowns.

With regard to the question of what is required, risk communication is considered a success if, when an individual makes a decision, they have been told everything they want to know and are in a position to think “I want to do this” or “It would be better for society if I did that.” Mutual trust between the party providing the information and the party receiving it is required to achieve this, and the basic assumption is that the information obtained contains no lies and that no important information has been concealed. Furthermore, risk communication can also be considered a great success if the relationships of trust are such that, even if the other party’s policy differs from the individual’s own views, the individual reaches the point of thinking “I can accept what that person (institution) says.”

Creating yardsticks to measure risk

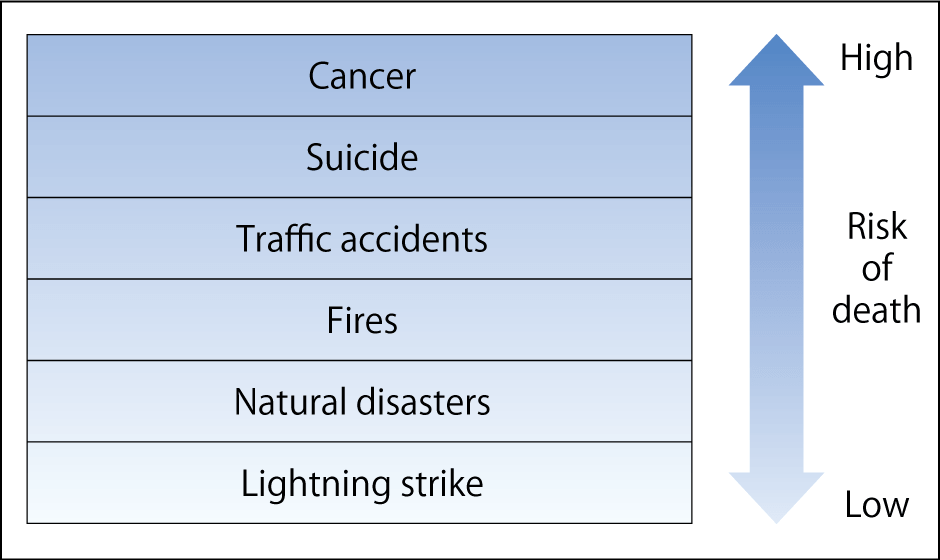

Making the decisions we think are best for us based on adequate information is an important way for us as individuals to face up to risk. Doing so requires us to grasp the scale of risk from a quantitative viewpoint. One thing I propose as an aid to this is the creation of yardsticks to measure risk. This involves trying to grasp the scale of a particular risk that we are facing by comparing it with other risk assessments familiar to us. For example, we can use for comparison data on approximately six events, including cancer, suicide, traffic accidents, fires, and natural disasters (Table 2). For this to function as a yardstick, we take as a benchmark the event that is most serious for a person and easiest for them to understand: death (number of deaths per year). Then we choose the comparisons to function as a comprehensive scale, running from quite high risks all the way to very slight ones.

Table 2. Examples of risk yardsticks (for comparison)Risk yardsticks cover the whole range from high to low risks. However, the degree of risk fluctuates according to the fiscal year to which the statistical data applies.

It is only natural that people intuitively feel anxious or afraid when faced with risk. However, I believe that if we consider a risk against a risk yardstick, we can think about the extent of the potential for us to come to harm in a more level-headed manner. Ideally, governments or other public institutions would provide risk yardsticks, which people could view online, for example, when needed. However, unfortunately, no such system has been put in place as yet.

In addition, it is vital to be aware of how powerful System 1 is and to make decisions using System 2 as well. Taking the example of COVID-19, while System 1 might make us want to go out and enjoy ourselves as we please, looking at it from the perspective of System 2, we can see how the infection spread because so many people in places like the U.S. moved around freely in the initial stages of the pandemic. Having said that, both psychological and financial problems arise if people isolate themselves completely. As we tend to be swayed by System 1, striking the right balance —— however imperfect it might appear —— in making judgments on how to reduce the risk of infection while enjoying ourselves and satisfying our desires to some extent is important to enable people to lead a healthy lifestyle.

When we take steps to counter one risk, another risk emerges. For example, if people stay home to combat the spread of infection, the risk of accidents within the home increases. In fact, 13,800 people died from accidents within the home (drowning, asphyxiation, falls, etc.) (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: 2019 Vital Statistics), which is higher than the number of traffic accident fatalities. There is also the risk that an earthquake could strike at any time without warning, so we also have to turn our attention to other risks, rather than fixating on just one.

We can never reduce risk to zero and there is no single right answer when it comes to measures to combat risk. What is more, we do not live our lives solely for the purpose of avoiding risk. Particularly when it comes to risks where the outlook is uncertain, such as in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, we need to accept the specific nature of such risks and then consider how to face up to them in our own way.