Quite a lot of people who dislike exercise say that it is because they have no sense of coordination, but there is no such thing as a person with innately slow reflexes. The inability to move one’s body in the way one wishes is due to the fact the individual has not built up many of the neural circuits that form as a result of experience. Avoiding an activity because one feels one is not good at it creates a negative spiral, causing a growing dislike of exercise. Overcoming that aversion involves reversing that spiral: if you train in an environment you find enjoyable and keep persevering at it, you will improve without fail, which will make it even more fun. Being able to experience this first hand in a palpable way is the real thrill of sport and exercise.

Special Feature 1 – Sport’s Hidden Depths You can conquer a poor sense of coordination if training is fun!

composition by Yuko Watanabe

illustration by Rokuhisa Chino

Quite a few people say they dislike exercise or have an aversion to it because they are not good at it. One often hears people explain their like or dislike of exercise, or their strong or weak points in that context as though the factors contributing to them were inborn talent or genes. For instance, people say, “I’m useless at all sports, because I’ve got no sense of coordination” or “I’ve got an aversion to exercise because my reflexes are slow, just like my parents.” However, there is no such thing as a person born with innately slow reflexes. Phrases like “I’ve got slow reflexes” (the Japanese phrase for which can be translated more directly as “I’ve got poor motor nerves”) and “I’ve got no sense of coordination” are based on nothing more than myths, and I want to stress that one’s own assumptions are factors that foster a dislike for exercise and contribute to a person being bad at sport.

There is no individual variation in motor nerve conduction velocity

What do we mean when we talk about “motor nerves” and “having no sense of coordination”? When bending your wrist, for example, an electrical signal that moves the muscles in your forearm is sent from the brain via your nerves, enabling you to perform the action of bending your wrist. The motor nerves are a set of neural circuits along which motor commands are sent from the brain to the muscles, leading to an action. Everyone is equipped with this system. This might make you think that information is conducted faster from the brain to the muscles in people who are good at exercise, but there is no variation between individuals in conduction velocity, nor is it affected by genes.

Whether we are talking about the small movements of daily life or the more dynamic movements involved in sport, the mechanisms involved are the same; all of these constitute physical exercise. We are not born with the ability to do everyday things like writing with a pen or eating with chopsticks from infancy; rather, by continually practicing them in day-to-day life as we grow, everyone gradually develops the ability to use a pen or chopsticks. You can see, therefore, that it has nothing to do with genes or talent. If your dominant hand is your right hand, it is because you repeatedly practiced writing with your right hand from early childhood that you can write and use chopsticks with your right hand. Surprisingly few people know that your dominant and non-dominant hands are not determined at birth; rather, the hand you repeatedly practiced using becomes your dominant hand.

We learn to ride a bicycle in childhood through repeated practice, and even if we have to ride one after many years of not using a bicycle, we can still do it, because our body remembers how to do so. While we talk about the body remembering how to move the various muscles required to ride a bicycle, our muscles do not actually have the ability to remember movements. What happens is that the neural signals for the movements required to ride a bicycle are initially sent directly from the cerebrum to the arms and legs. Then, as a result of practice, these neural circuits undergo revisions that are stored in the cerebellum. Practicing riding a bicycle causes electrical signals to repeatedly travel through these neural circuits, and the neural circuits acquired as a result are stored securely as memories in the cerebellum. Even after the passage of some time, a series of electrical signals is promptly sent to the requisite muscles through the neural circuits remembered by the cerebellum, enabling us to ride a bicycle.

You might argue that some people are good at any sport to which they turn their hand, so there must be some kind of gene or talent that influences how well our motor nerves function. It is true that, when learning to ride a bicycle, some people will be able to do it after practicing just a few times, while others will only succeed after 100 attempts. This is a matter of individual variation, but the outcome is the same: they have gained the ability to ride a bicycle.

The results of creating numerous neural circuits

One factor contributing to the emergence of variation between individuals is thought to be that, in the case of people who are able to do something immediately, they already have experience of a similar kind of exercise in their life up to that point, and the neural circuits formed at that time are remembered by the cerebellum. Consequently, when attempting a smash shot in badminton for the first time, for example, the individual is able to immediately draw upon neural circuits formed in the past when throwing a ball and can therefore move their body in the right way. In other words, when people have what is described as a “good instinct,” it could be described as the result of having experienced and practiced various movements in their environment since birth, enabling them to form numerous neural circuits relating to physical movement in the cerebellum and thereby acquiring deftness of movement.

On the other hand, it is conceivable that most people with an aversion to exercise have built up few neural circuits relating to physical movement as a result of experiences in their environment since birth. Being unable to draw upon these when needed, they feel that exercise is boring, because they cannot move their body in the way they want. It is this that causes people to start thinking they are no good at exercise and to dislike it.

With regard to the environment after birth, the period between the ages of three and eight years old is called the “golden age,” as it is the time when neurons develop and brain activity intensifies. Scientists believe it is the ideal period in which to acquire various movements and build up new neural circuit patterns. However, even if a person did not grow up in an environment that enabled them to experience various movements during the golden age, it certainly does not mean that it is too late for them to start exercising in adulthood. While it might take longer and require more practice to master physical movement as an adult than in childhood, because we weigh more and might have less muscle mass, exercise is one of those things where you are guaranteed to see progress if you just put in the practice.

We are fascinated by the deft movements of top athletes in sports such as soccer, baseball, and golf (Figure 1). Their most impressive movements that make us exclaim aloud at their skill are evidence of their complete control of their bodies, including their muscles, joints, and strength. To gain the ability to perform those movements, top athletes steadily engage in diligent training.

(Photograph: Aflo)

(Photograph: Aflo)

Figure 1. Top athletes in various sportsAthletes who compete with each other on the basis of efficient, deft performance achieved through consistent practice.

The field of sports biomechanics has been contributing to top athletes’ movement goals in recent years. Focused on applying the sciences of anatomy, physiology, and dynamics to the analysis of physical movement, this field of research has seen dramatic advances over the last 30 years.

In days gone by, sprinters in training were told they needed to lift their thighs high and swing their arms vigorously in order to run faster. This method had been developed through trial and error based on the experiences of coaches and athletes, but it was scientifically unproven and only athletes that it happened to suit saw their times improve.

Today, by using sports biomechanics to analyze the movements of skilled individuals, we are able to shed light on the theoretical aspects of how power is exerted to produce movement. Based on this information, we can create and offer to coaches and athletes a menu of training exercises that will enable people to achieve the same movements as those particularly proficient people. In the course of the activities to support Japan’s sprint teams I undertake as a member of the Japan Association of Athletics Federations’ Scientific Research Committee, I have used sports biomechanics to help Japanese athletes achieve outstanding success.

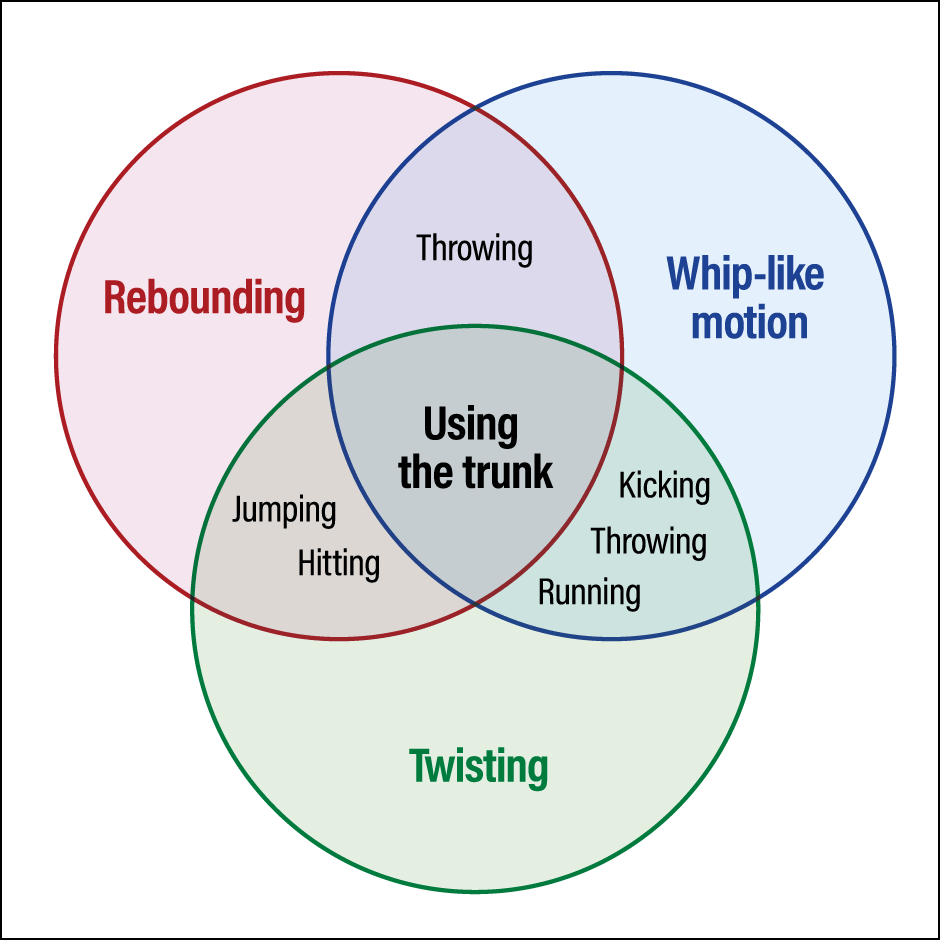

In various sports, four elements are always involved in achieving vigorous, dynamic movements (Figure 2). (1) Using the hip joints, centering on the trunk. (2) Using the twisting motion of the trunk. (3) Using the rebound. (4) Transferring energy to the arms and legs with a whip-like motion.

Figure 2. The four elements of dynamic movementThese four common elements are synchronized in all sports to produce the vigorous, dynamic movements that are crucial in sport. The key to improvement is being able to use all four elements to move the body smoothly.

Regarding the advice to sprinters that they should lift their thighs and swing their arms, scientists found that the speed with which the thighs were lifted was more important than the height to which they were lifted. By using the hip joints alone to lift the thighs, while relaxing the knees and ankles, sprinters can swing their legs forward like a whip, and striking the ground powerfully will then provide the power to propel them much further forward. I believe this discovery resulted in sprinters building up the muscles in their trunk and around their hip joints, creating more dynamic movement throughout their legs, which led to a reduction in sprinters’ times.

Persistence is the key to improvement

Drills (repetitive practice) are one effective means of learning correct form and technique, so I recommend them for everyone, from children to elderly people. I believe that persisting with appropriate drills helps people to acquire deftness of movement, eliminating unnecessary movement and thereby leading to improvements in exercise ability, just like in top athletes.

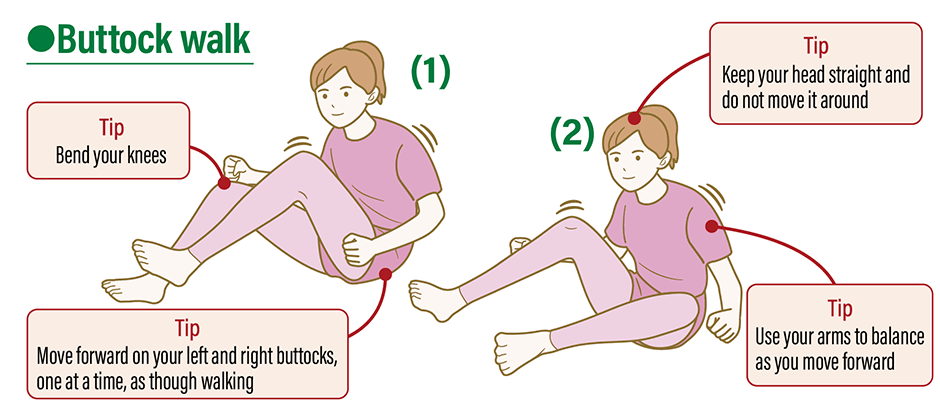

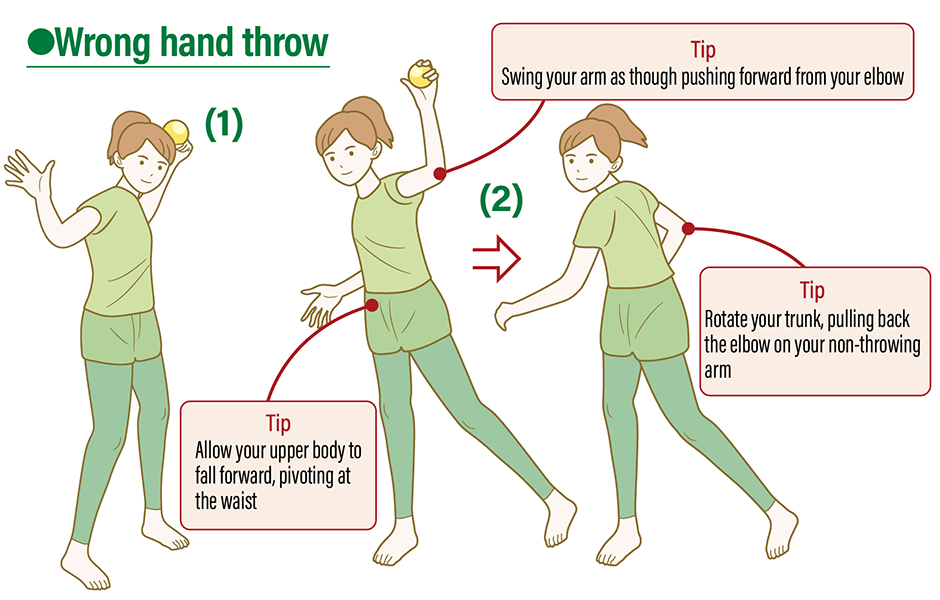

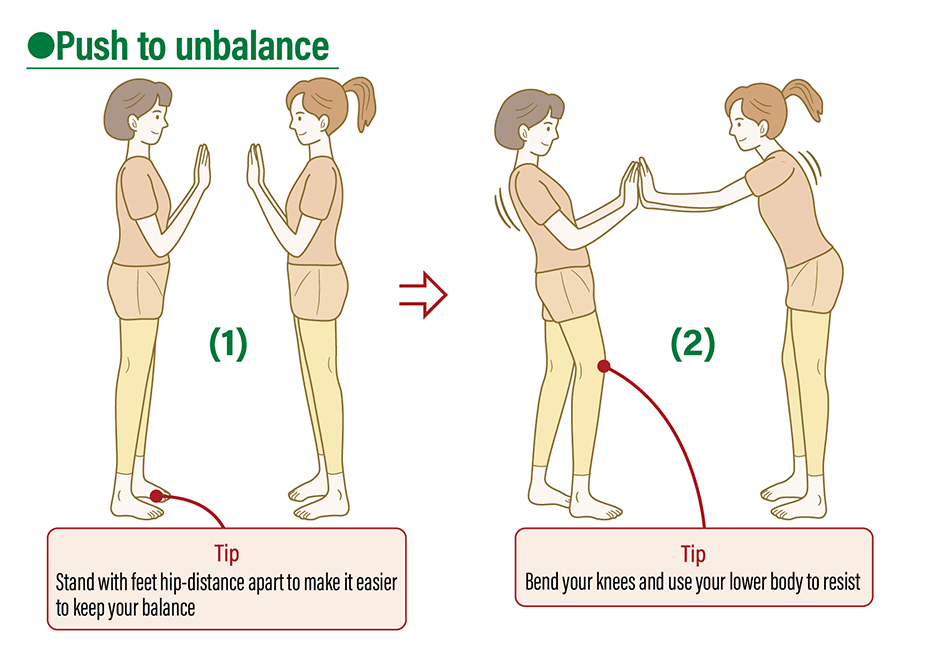

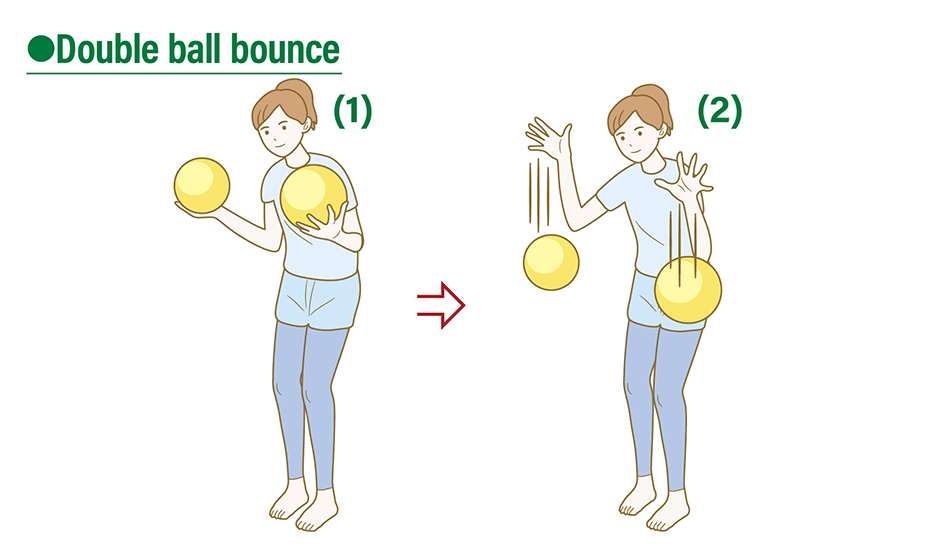

I would like to outline a couple of examples of drills you can do to improve your trunk strength and balance (Figure 3). Before starting any of these drills, please do thorough warm-up exercises to prevent injury, and stop the drills if you get too tired. I hope you will put them into practice, while also giving your body a rest as needed.

Figure 3. Examples of drills

Your trunk is the basis of every sport, and these drills focused on your trunk will also improve your overall balance, because you will need to make considerable use of your spine, to which people often do not pay much attention under normal circumstances.

Sit on the floor, bend your knees, and then move forward on your buttocks, lifting one buttock at a time. Then return to your original position in the same way. This drill gives you the ability to twist your trunk and move your pelvis, as well as developing your sense of balance by making you pay attention to your spine and trunk.

Throwing a ball with your non-dominant hand improves balance on the left- and right-hand sides of the body, helping to make your trunk more stable.

Improving your body’s balance functions gives you greater control over your body and helps to eliminate unnecessary movement.

In this drill, two people use their weight against each other. It cultivates the ability to sense the timing of when to push or pull, while feeling the other person’s movements.

Dribble two balls with both hands. Focus on trying to use the same degree of force while bouncing each ball under your hand. This drill develops your balance, which will give you the ability to bounce the balls with the same force and timing, including the way in which you deliver force with your dominant and non-dominant hands.

Allow me to introduce seven rules for achieving faster improvements in exercise ability. (1) Repeating drills several times is the fundamental key to improvement. (2) Practice drills based on an understanding of the significance of each and every movement. (3) If you feel as though you are getting nowhere with a drill, take a break. (4) Once you have got the hang of a movement, repeat it several times to create a stronger memory of the successful experience in your brain. (5) Even when you are not moving your body, imagine the drill in your mind. (6) Try applying good movements to other sports. (7) To ensure that bad movement patterns do not take root in your brain, review your results carefully and make revisions.

Quite a few middle-aged and older people suddenly make up their minds to take up exercise. One reason for such people starting to exercise is that they have been diagnosed with lifestyle-related diseases and exercise has been recommended as a way to prevent their conditions from deteriorating. It is difficult to keep up the habit of exercise for a long time if it is for the purpose of maintaining health or preventing disease, and one reason for this is that people do not find exercise enjoyable in itself. We are advised to walk 8,000 steps a day, but there is no fun in that if we do it out of a sense of duty. However, for people who enjoy golf, for example, walking rather than taking a cart around all 18 holes means they can walk not just 8,000 steps, but seven or even eight kilometers. People do not get fed up with doing what they enjoy or exercise they find interesting.

Accordingly, the key to keeping up exercise in the long term is to find something that you enjoy and devise ways to make it even more enjoyable. Rather than measuring the amount of exercise based on the number of steps or distance covered, you will find it easier to keep up if you do something you enjoy that also increases your physical activity, such as taking a walk while using your other senses to observe flowers and trees, for example.

The sense of achievement doubles the enjoyment

In addition, rather than comparing yourself and your abilities unfavorably to others, try comparing yourself to how you were a little while ago. Setting lots of small goals and surpassing each one is another tip for finding enjoyment in sport and exercise, because it ensures that you get a real sense of improvement. When practicing keepie-uppie with a soccer ball, you might only manage one time at first, but after continuing to practice, you will manage to do it five and then 10 times, and before you know it, you will be able to juggle the ball several dozen times. The sense of achievement from setting reachable goals and then surpassing them doubles the enjoyment.

As you keep practicing, your movements become smoother and you will have moments where you become able to move well. For example, if you play golf and once every so often you manage to hit the shot as you intended, it boosts your motivation to practice, because you think, “That went really well, so I’ll try this with the next step.” Repeated practice lays the paths via which your brain sends commands for your muscles to move. As these become firmly established, you will have numerous experiences of success.

Sport and exercise is an area where you get a very clear sense of how much you have changed from the way you were previously, and that is where their real thrill lies. I do hope you will incorporate exercise into your life, no matter how old you might be, and enjoy the opportunities it brings to transform yourself.