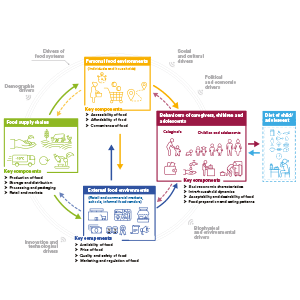

Why do children hate vegetables? Given that quite a few vegetables have a sour or bitter taste that induces a defensive response in the body, this is actually an appropriate reaction. However, children’s hatred of vegetables is something that bothers many caregivers. What can we do to alleviate that reaction and nurture in children the palate and skills that will prevent them from turning their nose up at vegetables? Experts say the process begins when babies are still in the womb. A well-balanced diet during pregnancy is also key to overcoming children’s dislike of vegetables.

Special Feature 1 – Children’s Nutrition Overcome aversion to vegetables via more frequent encounters with them

composition by Rie Iizuka

illustration by Koji Kominato

I must apologize for starting out on a negative note, but at present, one rarely sees any studies aimed at building evidence concerning picky eating in children in Japan. I think one reason for this is the difficulty of conducting such research, as interventional studies involving children entail substantial hurdles. Nevertheless, if we look at research overseas, I believe we can carry across certain general ideas concerning picky eating in children.

First of all, there are a number of things that influence food preferences not only in children, but also in adults. One is our genes. Many reports from overseas state that genetic factors are involved in eating habits such as overeating or undereating, and in our preferences for bitterness, spiciness, and other tastes. A British research team reported that individuals with mutations in melanocortin-4 receptors (MC4R), which are involved in regulating food intake, show an increased preference for high fat food but a decreased preference for sucrose containing food. A Spanish research team reported that the oxytocin receptor gene is associated with chocolate intake, while another research team reported that, for each extra allele at eight loci, the amount of coffee drunk increases by 0.03 – 0.14 cups per day. Thus, our preferences differ not only on the basis of what we have eaten and been fed, but also at the genetic level.

Many vegetables have an “unpleasant” taste

Preferences are also influenced by individual sensory factors. People inclined to hyperesthesia seem to be pickier eaters.

Particularly when focusing on children, most people are probably concerned about their hatred of vegetables. However, I think that children basically just have an aversion to vegetables.

One purpose of our sense of taste is to protect the body. It functions as a sensory organ to determine whether or not something is edible. From this perspective, bitterness is judged to be toxic, while sourness is deemed to indicate that food has gone rotten, which is why we develop a dislike of such tastes. As many vegetables also have such “dislikable” tastes, one could say that children’s rejection of them is a perfectly natural reaction. Thus, their starting point is a dislike of vegetables. It seems likely that individual preferences are then shaped once genetic factors and environmental factors are added into the equation, determining such matters as whether this dislike of vegetables continues, is overcome, or even turns into appreciation.

So, what sort of environmental factors are involved?

The key is exposure to vegetables–in other words, how much experience the individual has had of that taste.

The first crossroads is reached while the child is still in its mother’s womb. As taste buds —— the taste receptors on the tongue —— begin to develop in utero, there is a possibility that babies can sense taste before they are even born. Many studies have shown that the taste and smell of foods the mother has consumed pass into the amniotic fluid, and there is speculation that the child’s memory of these fetal experiences of such tastes and smells could possibly shape their food preferences. Accordingly, if the mother consumes vegetables, the baby in her womb could possibly also experience the taste of those vegetables.

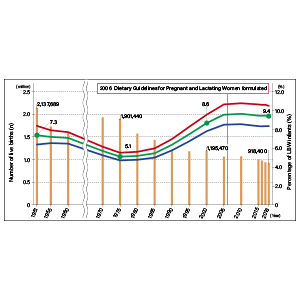

Once the child is born, the mother’s diet affects her breast milk in a similar way to her amniotic fluid, so breastfeeding influences the child’s experiences of taste. Here, too, the breast milk of mothers who eat vegetables can add to a child’s experiences of vegetable taste. There have been studies looking at likes and dislikes for vegetables in children who were breastfed and children who were fed on baby formula. The results show that breastfed children have less of a dislike for vegetables than children fed on formula.

Children breast fed for longer are pickier eaters

Many articles state that the period around five or six months of age, when weaning has begun, is very important. The Maternal and Child Health Handbook also contains a carefully considered explanation of how to approach weaning. Weaning should start by feeding the infant mashed up rice porridge. This will usually be followed a few days later by adding mashed potato, carrot, and other vegetables and fruit, and then gradually increasing the number of foods. In fact, there are studies showing that increasing exposure to a large number of vegetable types at this point helps to avoid a dislike of vegetables later on, and even some suggesting that children who were breastfed for longer are actually pickier eaters. Both from a nutritional perspective and from the standpoint of picky eating, it is necessary to begin providing children with meals enabling them to come into contact with a wide range of foods at this point.

Role models are also crucial for infants and young children. Children imitate their parents’ behavior —— this is called modeling. If the role model does not eat vegetables, the child watching them will also imitate that behavior. Thus, eating meals with someone who is a good role model is another important element.

What about children of school age? As their food preferences are already clear at this stage, they have a tendency to refuse to eat what they dislike, but eating with others, such as when eating school lunches, is believed to be effective in helping children to overcome a dislike of vegetables. It is quite common for a dislike of vegetables to be eliminated in the context of relationships with other individuals or groups. With school lunches, too, there have been reports that continued serving of vegetables that children are believed to dislike has led to an increase in vegetable and fruit intake among children. School lunches are a valuable opportunity for children to be exposed to a variety of different foods, without thinking of them as vegetables. The same is true in the home. It is important to keep serving foods, rather than not serving things because the child will not eat them. And praising them a lot if they do manage to eat something they dislike works as a highly effective incentive. What you absolutely must not do in such circumstances, however, is to reward them with other foods, such as treating them to their favorite chocolate if they eat a vegetable to which they have an aversion. Rewarding them with a food they like can reinforce their negative feelings toward vegetables.

The older children get, the harder it becomes to conquer their dislike of vegetables, so in addition to school lunches, there are initiatives called shokuiku (education about diet and food) programs aimed at helping them overcome their aversion to certain foods. Rather than those focused solely on eating, composite programs that also incorporate interactive experiences of agriculture and cooking are believed to be somewhat effective in overcoming a dislike of vegetables.

Attention must also be paid to cooking methods in order to reduce aversion to vegetables. Recipes highlighted on websites and the like as helping to overcome children’s dislike of vegetables often involve preparing the vegetables in such a way that children will barely notice them, such as grating up carrot to mix in with the meat when making hamburger steak. While this might have the advantage of disguising vegetable taste a child might dislike and even the presence of the vegetable itself, making it easier for them to eat, it also has the disadvantage that it does not directly help them to get used to the taste of the vegetable they dislike. Of course, successful experiences of eating a food can often help to overcome an aversion to it, but thinking in terms of exposure to vegetables to which a child has an aversion, diluting their exposure to them could ultimately result in their failing to conquer their dislike. It might be advisable to avoid this approach when children first develop food preferences, and to try it only when all else has failed.

Provide a variety of eating experiences

Comparing children who are served a large number of different vegetables and those served only a few, the former demonstrably have less of an aversion to vegetables. From this, we can say that exposure to vegetables has a high probability of reducing a dislike of them. In fact, this starts when the child is still in the womb. Researchers have found that differences in children’s future aversion to vegetables emerge depending on their exposure to vegetables at a number of key stages —— that is to say, the extent to which they have experienced the taste of the vegetable itself. To reduce children’s dislike of vegetables, it is helpful to enable them to experience a variety of different tastes in order to prevent them from perceiving them as unpleasant, and also to undertake efforts tailored to each life stage.

As part of my research, I undertook a study of how food preferences in early childhood changed in adulthood. I conducted this study in Oita Prefecture among the staff of kindergartens, nursery schools, centers for early childhood education and care, the guardians of children attending such childcare facilities, and university students. As I work in a research and education institution focused on nutritional science, I have frequent contact both with teachers at nursery schools, kindergartens, and centers for early childhood education and care, and with the guardians of children who attend those facilities. The question they most often ask me is how to overcome picky eating in children. Accordingly, I decided to investigate what kind of foods children dislike, the reasons for this, and what kind of changes occur later on.

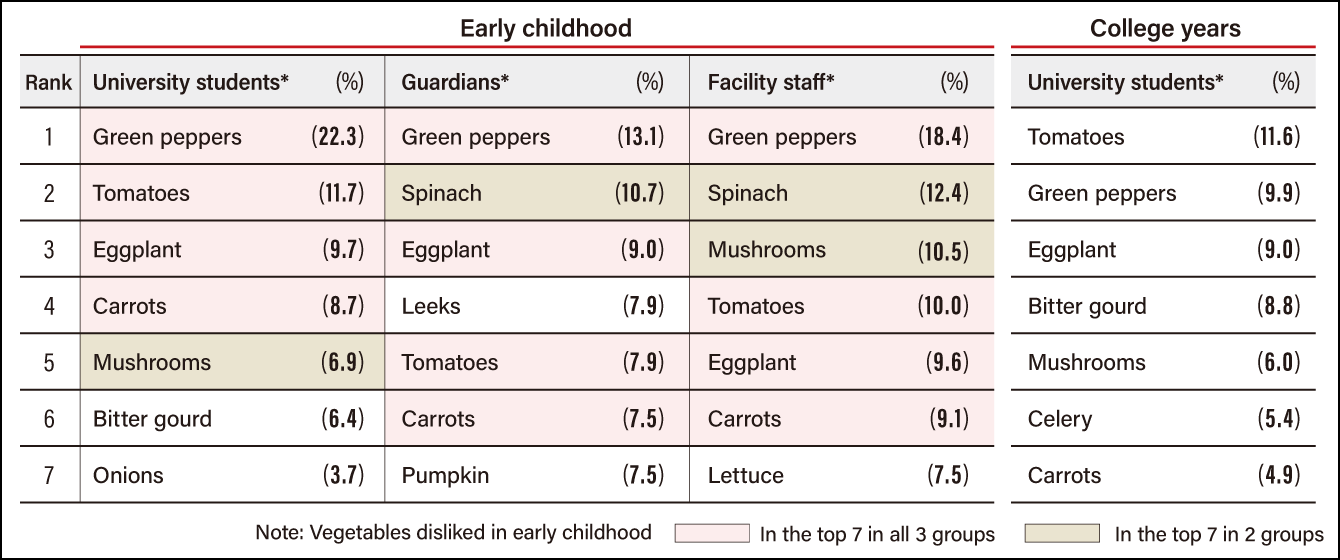

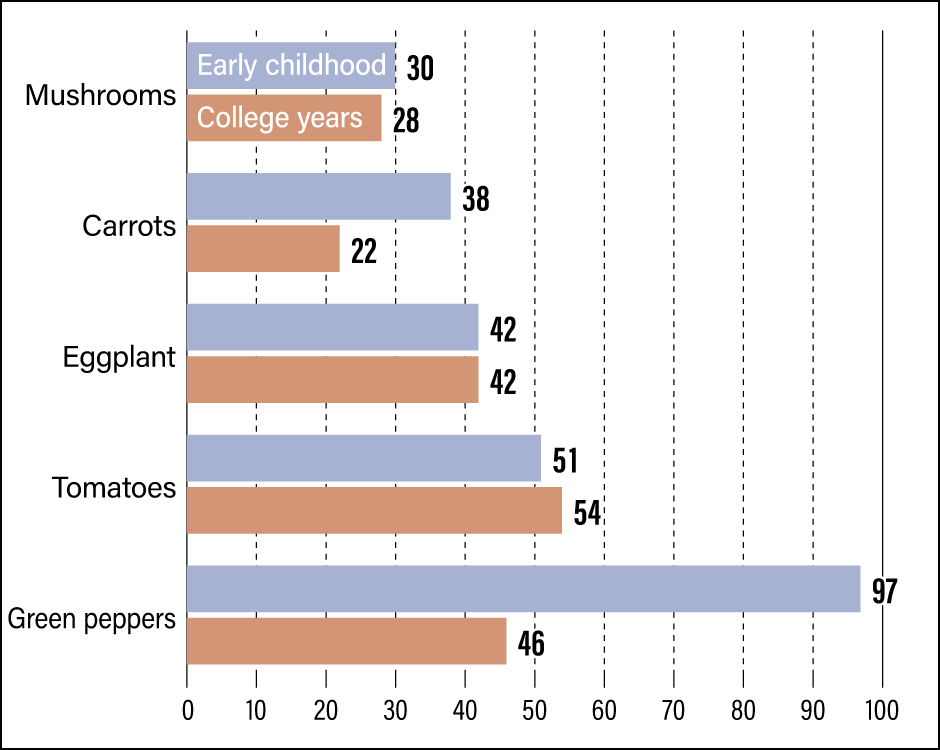

In response to my survey, 66.8% of guardians stated, “My child is a picky eater.” Looking at the specific foods the children disliked, the top seven were all vegetables, with green peppers in first place, followed by spinach in second. Next, looking at the responses from university students, 80.5% stated, “I was a picky eater when I was a child,” listing green peppers, tomatoes, eggplant, carrots, and mushrooms as the top vegetables they had disliked in early childhood (Table 1).

Multiple responses permitted regarding foods disliked

Multiple responses permitted regarding foods disliked*Questionnaire respondents (421 university students, 250 guardians, 150 childcare facility staff)

Table 1. Ranking of foods disliked in early childhood and college yearsThis table shows the responses provided by guardians and childcare facility staff when asked which foods children they cared for disliked and by university students when asked which foods they had disliked in early childhood. Green peppers ranked top in childhood and in second place during the college years, with the other vegetables appearing in different sequences. Most notably, tomatoes ranked top among students during their college years.

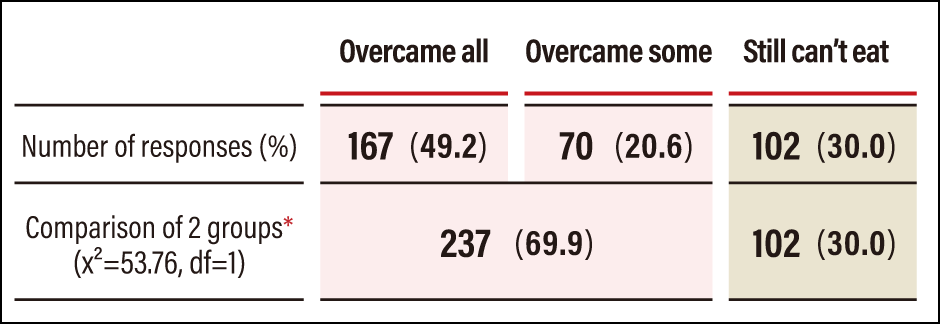

When asked whether they had any dislikes now, 79.3% stated that they did. In fact, the top foods the university students reported disliking now are much the same as in early childhood —— tomatoes, green peppers, and eggplant —— demonstrating that half had maintained the same dislikes since early childhood (Figure). However, we must not overlook the fact that 70% stated they had become able to eat some or all of the foods they had disliked in early childhood. This suggests they had, in the process, somehow developed skills that eliminated their pickiness. Conversely, however, the fact that almost half of the students reported still being unable to eat certain foods even in their college years and that most of these foods are vegetables is a problem, suggesting that they might not have had the opportunity to gain the relevant skills before becoming university students (Table 2).

Number of responses (Multiple responses permitted)

Number of responses (Multiple responses permitted)

Figure. Changes in foods dislikedComparing the top five foods disliked in early childhood and during the college years, the number of respondents citing a dislike of tomatoes, eggplant, and mushrooms barely changed. Only half still disliked green peppers and carrots in their college years.

*Comparison of 2 groups = “Overcame all or some” and “Still can’t eat” p<0.001

*Comparison of 2 groups = “Overcame all or some” and “Still can’t eat” p<0.001

Table 2. Success in overcoming aversion to foods49.2% of respondents stated they “can now eat all (overcame all)” foods they disliked in early childhood, while 20.6% stated they “can now eat some (overcame some).” However, in another response, 49.1% stated “I still (in my college years) dislike the foods I disliked in early childhood (no change).”

Broadening our perspective a little from aversion to vegetables, Japan faces an issue in that it lacks a systematized program to cultivate food skills. While work on shokuiku is being carried out in numerous settings, dietitians and others involved in the field are engaged in their own individual activities at present. There are huge individual differences in food preferences, so there is no single correct answer as to which program is the right one, but at the very least, I feel there is a need for a systematic, evidence-based program.

One program I have recently been implementing is the Puisais method. The taste classes known as the Puisais method have been conducted since the 1970s in France, which is famous for its cuisine. Advocated by oenologist Jacques Puisais, this approach involves providing education in which students learn to use all five senses in tasting (taste education). By using all five senses in engaging with foods and verbalizing what they felt, students gain the ability to feel and think for themselves, the ability to make judgments from feelings, and the ability to express what they feel and share it with others.

The need for an evidence-based program

These classes include a program in which the students first experience processes stimulating the senses before food is cooked, such as touching vegetables while blindfolded and listening to the sound of ingredients being cut up. They then verbalize the associations conjured up by those sensory experiences and finally eat the foods. This set of programs aims to have children use their imagination and senses to the fullest, and to fully discover each food, including through taste. I have already stated that exposure helps to overcome an aversion to specific foods; the method used in this program could be said to deliberately provide not only children’s sense of taste, but all five of their senses with exposure to different foods. Research in other countries has demonstrated the effectiveness of this program, and I myself am working on implementing it as an approach to reducing pickiness about food.

Today, in addition to the Puisais method, a number of other approaches are becoming more widespread, primarily in Europe, including the Sapere method, which incorporates the ideas of Puisais. The methods are highly interesting in their own right and include content rarely seen in Japanese shokuiku, but the most important thing is the fact that such systematic programs exist. I strongly feel that Japan, too, needs an evidence-based program.

Many studies have shown that vegetable intake among adults is lower among those who do not eat breakfast. This might be because eating two rather than three meals a day means that the amount eaten overall decreases. Missing breakfast might also be indicative of an individual’s overall attitude to food. Similarly, we know that people who cook for themselves eat more vegetables than those who do not.

Being picky about food is a source of stress for adults and children alike, and one could even go so far as to say that they lose out by being unable to enjoy food. To avoid the development of pickiness as far as possible, it is important to give children the opportunity to encounter a diverse array of foods from the time they are in the womb right through until they are at school.